Six Miles to Charleston (4 page)

Read Six Miles to Charleston Online

Authors: Bruce Orr

Of course being a proprietor of one, or several, of these inns could be advantageous. Traders, avoiding the higher costs of the city, may take advantage of your inns. If you were an honest proprietor, you could make a fair wage taking care of your customers. Add the care of the horses and the price goes up.

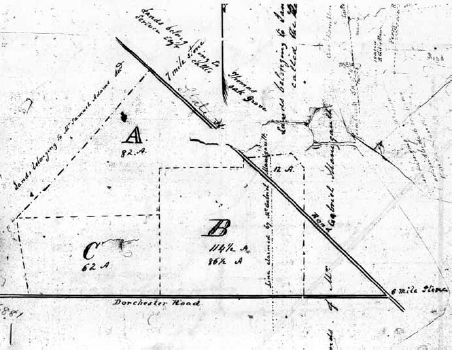

A map of the Charleston district by Robert Mills, dated 1825, actually has several of the taverns locations denoted. Six Mile House, rebuilt after being destroyed by fire six years earlier, was a little beyond the intersection of Goose Creek Road, now Highway 52 or Rivers Avenue, and Dorchester Road. The Four Mile House was, of course, a little closer to the city.

The Four Mile House is often, erroneously, said to be the location of the Fishers' crimes. In the

South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine

(volume 19, January 1918âJanuary 1919), it appears that Judge Henry Augustus Middleton Smith identified the Four Mile House as being upon a tract known as Discher Farm. That is true but then he states, inaccurately, that it was the scene of the incidents with the Fishers. His confusion may be due to the fact that the Four Mile House was originally called the Six Mile House in the 1700s, not the 1800s when the incidents took place in the location ran by the Fishers. The first mention of the place Smith is referring to being called the Four Mile House Tract is in a 1786 deed of sale from James Donovan to John Bowen.

According to research, the Four Mile House was demolished in October 1969 after several efforts were made in a four-year effort by the preservation society to maintain it as a landmark. The house and its four-acre plot were purchased by the Milton F. Truluck Trust and was the remaining portion of the seventy-acre plot on which the inn was built. Edward Evans, a member of the demolition firm, was interviewed and stated that he saw no hidden compartments, trapdoors or cellars on or around the house during the demolition.

Leaving Charleston along what was once Goose Creek Road, one can locate Discher Road and Four Mile Road. They are apparently the only reminders left of the Four Mile House and its seventy-acre tract.

A little over a mile from that location is Five Mile Viaduct. A little over two miles from there behind Whipper Barony subdivision is an area known as Seven Mile and lastly, at the Intersection of Highway 52 (Rivers Avenue) and Remount Road is a business park known as Ten Mile Station. Although the taverns have been long gone, it is obvious that the mileage designations created back then are still used to this day.

In overlaying and comparing plat 6881 and a current map, one gets a general idea of where Six Mile House was. The Six Mile House would have been in an area now occupied by the Charleston Naval Health Clinic, previously known as the Charleston Naval Hospital. This nestles it directly between and across from the Charleston County Sheriff's Office and the North Charleston Police Department Substation. It is quite ironic, and somewhat humorous, that this legend of one of the most vicious female serial killers in the state of South Carolina originated on the very doorstep of not one but two of this state's largest law enforcement agencies. What is even more ironic is that one of those agencies evolved from the elected position of the person who arrested the Fishers. The Office of Sheriff of Charleston back then is now known as the Charleston County Sheriff 's Office today. This agency now employs hundreds of deputies and is divided into numerous specialized divisions.

Plat 6881 shows the location of Six Mile House near the intersection of Dorchester Road and Goose Creek Road, which is now Rivers Avenue.

Courtesy South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

Four Mile Lane in the vicinity of where Four Mile House once stood.

Courtesy of author.

Discher Street where Discher Farm once stood, a tract containing Four Mile House.

Courtesy of author.

Five Mile Viaduct where Five Mile House once stood.

Courtesy of author.

The Charleston Naval Clinic, formerly the Charleston Naval Hospital, now sits where Six Mile House once stood.

Courtesy of author.

With the wagon and stage trade prevalent, the traders themselves became targets for highway robbery. If a full wagon was heading into town, one could easily hijack the wagon and take the goods for themselves. If one were leaving town with an empty wagon, then one could assume that the goods had been sold and the trader was carrying cash.

In the early months of 1819, highwaymen were busy. A citizen, James Addison, had been robbed of a little over $10.00 at dusk by a white man mounted on a white horse. John Brown had also been robbed and deprived of $140.00. Others had been lured into the inns where they were cheated in crooked gambling games. Added to those complaints was that of Stephen LaCoste, who had gone to his pasture to check on his cow and found the creature missing. Mr. LaCoste was quite certain the cow had not wandered off and had met with a much more diabolical fate.

Those involved in the wagon trade, along with anyone else traveling to and from Charleston, felt it necessary to carry their rifles for protection. This frustrated the citizenry of Charleston, and they had had more than enough. They feared that the news of such robberies would deter trade and create even more problems to the already failing Charleston commerce. Younger and smaller towns such as Cheraw, Camden, Columbia and Hamburg were already in a position to intercept the wagon trade, and the threat of robbery was sure to divert these merchants to these smaller towns and their smaller wagon yards.

On February 16, 1819, a mob set out from Charleston to take the matters into their own hands. Well armed, determined and riding under their own authority, they set out for the Five Mile House. They set forth under “Lynch's Law” and no other authority at all.

The term Lynch's Law was used as early as 1782. A prominent Virginian named Charles Lynch created his own laws and terms in suppressing a suspected loyalist uprising in 1780 during the Revolutionary War. The suspects were given a trial at an informal court. The sentences handed down included whipping, property seizure, coerced pledges of allegiance and forced enrollment into the military. Charles Lynch's extralegal actions were retroactively legitimized by the Virginia General Assembly in 1782.

A second explanation of Lynch's Law comes from another source. In 1811, Captain William Lynch claimed that the phrase “Lynch's Law” actually came from a 1780 compact signed by him and his neighbors in Pittsylvania County, Virginia. The compact allowed them to uphold their own brand of law outside of legal authority. Regardless of the origins of Lynch's Law, it was nothing more than mob justice without legal authority. The state of South Carolina eventually created laws against such acts.

Lynching is now a felony. Lynching in the first degree, section 16-3-210 of the South Carolina Code of Laws, deals with the death of a person at the hands of a mob. Any person found guilty of lynching in the first degree shall suffer death unless the jury shall recommend the defendant to the mercy of the court, in which the defendant shall be confined at hard labor in the state penitentiary for a term not exceeding forty years or less than five years at the discretion of the presiding judge.

Lynching in the second degree, section 16-3-220 of the South Carolina Code of Laws, is an act of violence by a mob in which death does not occur. It is a felony and any person found guilty of the crime shall be confined at hard labor in the state penitentiary for a term not exceeding twenty years or less than three years at the discretion of the presiding judge. While lynching in the first degree is rarely used when a charge of murder will suffice, second-degree lynching is still utilized in cases of gang violence within the state. It is considered by investigators to be the state's gang statute. That is exactly what a gang is: it is a mob gathered together in unison to commit violent and criminal acts. Then again, in present-day South Carolina, lynch mobs, or gangs, are illegal. The year of 1819 was quite different. Remember that colonial justice does not equal criminal justice, but we will cover that in a later chapter.

Apparently a gang of these robbers had set up shop in the area of Ashley Ferry just outside of Charleston. The robbers could not be identified by any of the victims, so the lynch mob set out to find and disband the group and force them away from the inns in the area. They allegedly had permission from the owners of several small houses in the area to proceed as they saw fit. The fact that the Charleston newspaper, the

Courier

, reports that this group set forth to find and drive away a group they could not even identify is quite interesting.

The mob arrived at a house commonly called the Five Mile House and found a small group gathered there. The group was ordered to vacate the premises and was given fifteen minutes to comply. When they protested, resisted and failed to comply in leaving the building, the lynch mob responded by setting the building on fire. In a very short time it burned to the ground along with some adjacent outbuildings. The Five Mile House was completely destroyed.

The lynch mob then reorganized and proceeded farther up the road to Six Mile House to repeat the process. The same order was given to vacate, and this time the occupants thought it best to comply quickly. Rest assured that the smoke and ash in the February air blowing from the remains of Five Mile House was incentive enough. So were the warnings of its former occupants. After the occupants had departed and the Six Mile House was vacant, the lynch mob placed a young man inside to watch over the property. That man's name was David Ross.