Small Man in a Book (20 page)

Read Small Man in a Book Online

Authors: Rob Brydon

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

The most telling piece of advice or observation that he uttered that day, though, was this: ‘It’s very hard to get to the top in this game, but it’s a damn sight harder staying there.’ That has never been far from my mind, from that day to this.

So, why such a fan of Sir Jim? Well, he’s a one-off; there’s no one else like him, and that surely should count for something.

I loved his radio style too. How about this (he’s just played ‘Way Down’ by Elvis)?

‘Elvis. “Way Down”. But … way … up … in … the … minds … of … his … many … fans.’

Then he played the next record. That was the link. Brilliant.

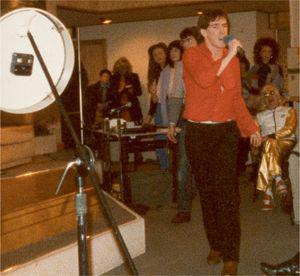

Our debut radio performance went well, the audience liked us, and we were deemed a success.

Prowling the stage like a promiscuous panther …

Hurrah!

I very much liked the atmosphere of the broadcast, the efficiency of the team as they bustled around preparing the programme and completing last-minute checks before the audience was allowed in and the show began. Rather like when I auditioned for the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, this felt within my reach. Far from feeling especially daunted by it, I saw it more as a challenge at which I was fairly confident I would succeed.

Buoyed by this success, I would revisit St David’s Hall every Friday lunchtime and loiter around the production team in the hope there might be something to do. There often was – basically, in the form of providing a silly voice for an announcement or sketch, which I was more than happy to supply.

I was, quite unknowingly, taking the first steps towards my subsequent career. At the time, it simply felt as though I was going with the flow, taking an opportunity as it arose.

10

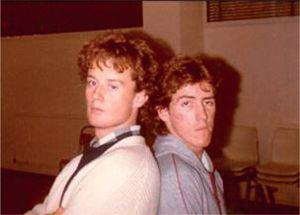

Back at college, James and I were flushed with our success and decided to take the band on the road. We secured a booking at the Wyke Regis Working Men’s Club. This was in a small town near Bournemouth, of which I had up to that point been unaware. James came from Hampshire so I suspect it was his idea, although I doubt he had any personal knowledge of the place, coming as he did from the other end of the social spectrum. The gig provided a modest fee, which we never saw; it failed even to cover the cost of renting a car to get us there in the first place, to say nothing of the petrol. So we were down on the deal before we started, but it didn’t matter. We weren’t in this for the money; that would come later. We were in this for the experience. And that’s what we got.

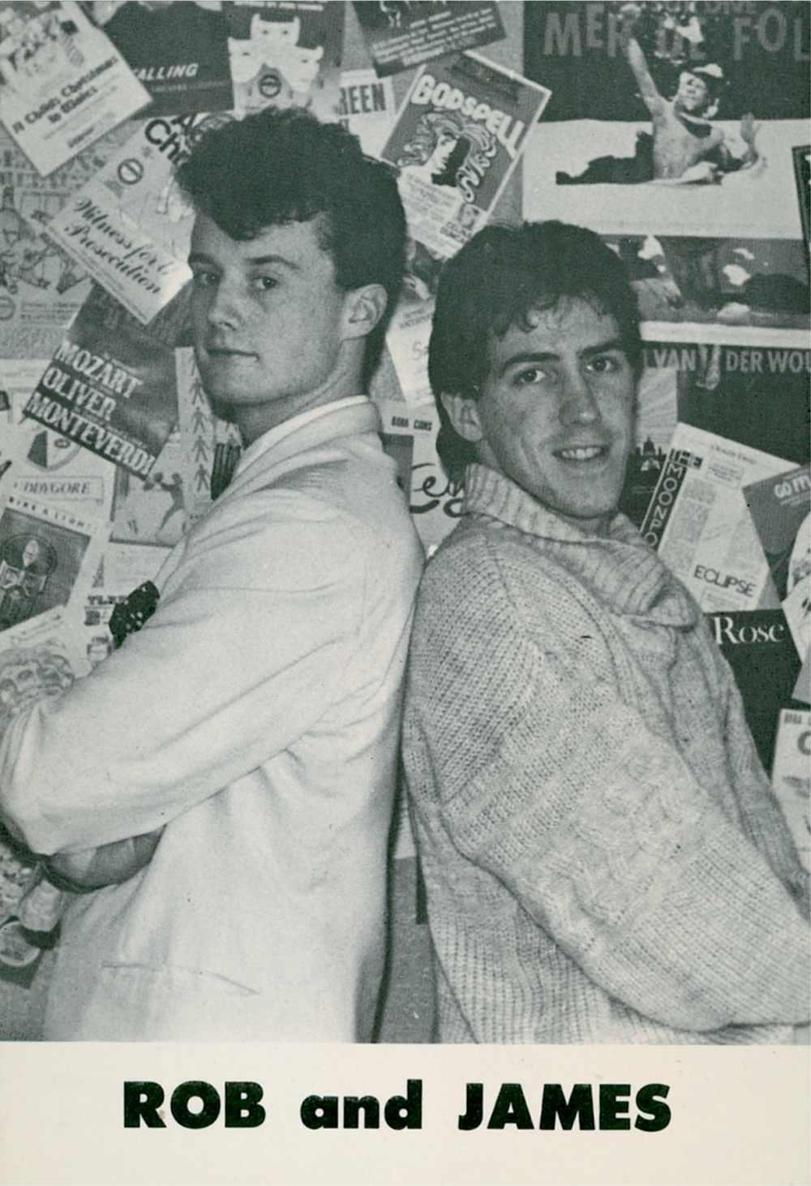

With James, evoking the spirit of a young Stallone.

We arrived at the venue after our long drive to see a list of the week’s attractions pinned to a board in the foyer. We scanned it with ill-concealed excitement, keen to see our names in print. It was a roll-call of the sort of acts you see advertising their services in the back of

The Stage

newspaper – the foot soldiers of show business, toiling away in the trenches of low-paying, hard-graft entertainment. Still, our names were going to be on there and that meant we had arrived. Admittedly, it was only Wyke Regis Working Men’s Club. But for us it was an arrival nonetheless. Finally spotting our billing, it would appear that we hadn’t in fact arrived; rather, it was someone who sounded almost but not quite like us. There on the board under tonight’s date was the name Robin James. Hmmm, there’d evidently been a breakdown in communication and somewhere along the line Rob and James had matured into Robin James.

Not to worry, it doesn’t really matter

, we told ourselves as we set about lugging the equipment in from the budget-breakingly expensive rental car.

A couple of hours later, we launched into our act to a room that was filled to perhaps a quarter of its capacity. The inhabitants seemed, to our young eyes, to be on the other side of old, and we set about assaulting them with ‘Crocodile Rock’, ‘Hungry Heart’ and other foot-tappers of a similar ilk. The crowd, if it could be called that, seemed unimpressed but we carried on gallantly with our collection of upbeat tunes performed to the simple accompaniment of an electric piano, no percussion in sight. Our elderly audience grew less impressed by the minute; these people didn’t have time on their side and were livid at the prospect of it ebbing away in our company.

After a very long period of us singing inappropriate songs into an empty void of nothingness, a blue-haired lady edged towards the stage, crossing the vast desert wilderness of the empty dance floor before coming to a faltering halt right in front of us. She smiled sweetly, but underneath the smile was a steely undercurrent that told us she was not to be messed with. Like Brian Dennehy’s redneck sheriff telling John Rambo that he wasn’t welcome in this town, she said, ‘We don’t want this kind of music. We like waltzes, you should play a waltz …’ Of course we didn’t have any waltzes in our set list, or even up our sleeves. We were strictly rock ’n’ roll. Pop, perhaps. But certainly not waltzes. Necessity being the biological mother of invention, we came up with a solution – one which still impresses me now, twenty-five years later, for its sheer guile and cunning. We had with us

101 Easy Hits for Buskers

, a huge groaning book of sheet music within which was ‘Can’t Help Falling in Love’. Now this may already be in 3/4 time – I don’t know, I’m not a proper musician – but what I do know is that we hammered the hell out of the song in a strict 3/4 rhythm, snapped out by my fingers as they conducted the dancing.

‘Wise [

boom, boom

] men [

boom, boom

] say [

boom, boom, boom

] only fools [

boom, boom

] rush [

boom, boom

] in [

boom, boom, boom

] …’

It worked. The disappointed dancers, to their credit, slowly shuffled on to the dance floor and gamely supported our last-ditch effort at entertaining them. With a quarter of the available floor space bulging to capacity we sang and played on until there was no more ‘Can’t Help Falling in Love’ to give and we couldn’t help stopping.

‘Well, that’s all from us, ladies and gentlemen. Thank you very much and good night!’

We left the stage to applause best described as angrily polite, and collapsed into a couple of chairs at the side of the dance floor in a heap of nervous exhaustion. We looked at each other. There was nothing to say. We had survived – just. Let’s leave it at that. While we were sitting there trying to comprehend the scale of our humiliation, we noticed a gentleman heading over to us. It was the chap who was in charge of the evening; we’d spoken to him briefly on our arrival when, for all he knew, he’d stumbled on the new U2. We were sure he wouldn’t have been overly impressed, but perhaps he’d admired the way we pulled the Elvis song out of the bag and almost turned the audience around. He stopped a couple of feet away from us. He didn’t smile.

‘You’ve got another ten minutes to do. Get back on.’

A recurring fear in my professional life has been not having enough material for my designated slot. Whether it’s been the West End, a tour, or a spot on a charity show at the O2, it is something that has dogged me for as long as I can remember. Only now does it occur to me that this may have been the birth of my condition. Thank you, Wyke Regis Working Men’s Club social secretary. Thank you very much.

We dragged our feet back to the stage and managed another ten minutes of faux waltz music to an audience giddy on a heady cocktail of anger, pity and contempt. When the ten minutes were up, we looked over to the social secretary. He gave the cold, steely nod of the professional executioner (‘Goodbye, Mr Bond …’ ), a thin smile spreading imperceptibly across his lips. We trudged back to the chairs at the edge of the dance floor and sat staring at our feet, scanning the floor tiles for a silver lining, when a pair of comfortable shoes entered our view. They belonged to a man, perhaps in his seventies, with a soft friendly face and a kindly disposition. He looked at us and thought for a moment. We knew he was about to tell us that it hadn’t been as bad as we’d thought and that he’d enjoyed it anyway, so what do

they

know?

He began to speak.

‘Boys, I’ve been coming here for a long time, seen a lot of acts come and go over the years, but I have to say, you were the worst I’ve ever seen. You were crap.’

He turned and was gone.

We packed up our equipment in next to no time, jumped into the ‘never more expensive than now’ car, and began the journey home. These were the now-forgotten days before satellite navigation so I have to assume that we would have conversed at some point regarding the best route back to Cardiff. Try as I might, though, I can’t recall a single word being spoken the entire length of the journey.

It’s an odd thing about performers, artistes, ‘turns’, call us what you will – and it will, I’m sure, become a recurring theme throughout this book – that no matter how bad the beating, how great the humiliation, we always dust ourselves down and get back in the ring. So often, comedians are told by friends and family, ‘I don’t know how you do it.’ This is to miss the point. All the successful comedians, actors or musicians that I’ve known have had one thing in common. Their job is a calling, not a choice. It’s something that I’m sure annoys the hell out of people with a degree of contempt for those whom they view as self-absorbed luvvies, but it’s true nonetheless. It’s something the person feels compelled to do, as opposed to a choice made while chatting to a careers officer on a wet Tuesday afternoon at the local school. It’s a feeling of having something to say, of wanting to get something ‘out’, and it’s what carries you through the traumas of many hostile audiences.

We experienced a few more, James and I, in those early days with everything ahead of us and no guidebook to consult along the way. There was a nightclub in the centre of Cardiff called Jacksons, which in the mid-eighties was a fairly upmarket, sophisticated sort of place. It was a step up from Bumpers, another celebrated haunt for nocturnal Cardiffians, which had a more downmarket feel. Jacksons seemed the sort of place for young people on their way up; if a soap star was in town for an opening of a shop or an envelope, Jacksons was where you might find them relaxing after a hard day’s smiling. It had a touch of glamour (to my Port Talbot-trained eyes, anyway) and was undoubtedly a step in the right direction, a little further up the evolutionary ladder of sophistication than the Troubadour, sitting snugly as it did in the shadow of Cardiff Arms Park. It even had a dash of showbiz thrown into the mix with the presence of a manager who had recently appeared on

Blind Date

. Cilla Black’s massively popular dating show was huge and, although a little racy at the time, now of course appears positively Edwardian in its values.

James and I somehow landed a try-out at the club. We were to perform early one evening, before too many of the paying customers had come in, and we had the added excitement of knowing that a coven of the company’s directors would also be in attendance, judging our fledgling performance. I don’t remember if we were nervous. Maybe we were. As I’ve said, there were some situations that I just didn’t get nervous over; I felt I was better than them, and therefore they were lucky to have me. This may have been one of them. What I do remember with alarming clarity is the sight of the celebrated blindly dated manager, one and a half songs into our try-out, walking hurriedly towards us from the huddle of directors while making a cutting motion across his throat.