Small Man in a Book (24 page)

Read Small Man in a Book Online

Authors: Rob Brydon

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

Rhys was working with Mark, and I clearly remember my first sighting of him as I was being shown around the offices on the second floor of Broadcasting House. I popped my head around the door of his office and there he was, in his leather jacket, unshaven, with mountains of long black hair; he looked like he was enjoying a day off from his main job as a roadie for Motörhead. Just as I had when first sighting James, my best friend at college, I thought to myself,

Hmm, we’re not going to be spending much time together

. Rhys, like Mark, was both a presenter and a producer and would go on to take charge of my Saturday morning show, a job which allowed us acres of time to do very little in the way of work. We would slope off in the middle of the day to play golf, go tenpin bowling or loll around in the health club at the recently built Holiday Inn where I was a member.

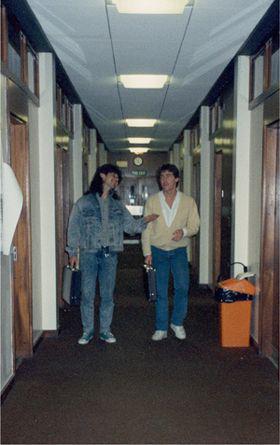

Rhys.

Rhys and I at BBC Wales. Despite the briefcase, we did very little work.

We were two young men in our early twenties, living the life of someone in his sixties who has retired through ill health and is slowly rehabilitating himself after a heart-related incident. Looking back on this period, I get a little cross with myself when I think of all the time I wasted, when I could have been more focused and working on an act. But I think I was such a late developer that it could only ever have happened the way it did.

Once I’d been a regular presence on the radio for a while, I began to gain enough of a name to receive the odd invitation to attend or host local events. These requests would come straight to the office at the BBC as I’d yet to find representation. Rather than deal with potential employers myself, I invented an agent and would play him on the phone.

Richard Knight was part of Knight and Day Management and spoke with a gruff London accent, a kind of Arthur Daley figure who could demand more money than I would have been able to ask for with a straight face. I’m ashamed to say that he would sometimes manage to get a modest fee from societies who’d asked me along despite obviously not having much spare cash knocking around. I remember one time calling a very nice, rather timid-sounding lady who wanted me to host an evening for underprivileged kids. I managed to get a fee for what I now realize was a charity evening.

‘Is that Mrs Jenkins?’

‘Yes.’

‘Hello, Mrs Jenkins, this is Richard Knight of Knight and Day Management. I’m calling about your letter to Rob.’

‘Oh yes –’

‘Now I’ve had a look at the date and I think we might be able to manage something, but I’ve got to bring up the sordid subject of money.’

‘Oh well, the thing is, Mr Knight –’

‘Please, call me Richard.’

‘All right, Richard, the thing is –’

‘Let’s go for Dick.’

‘Ooh –’

‘Can you go for Dick? Are you comfortable with Dick?’

‘Well, I suppose so … Dick.’

‘Now the thing is, Bobby is a saint, he’d do it for nothing, but I wouldn’t be doing my job if I didn’t try and squeeze a little bit out of you.’

‘Right.’

‘So, how about this? And I’m not going to squeeze you tight.’

‘No.’

‘We won’t say a pony, we won’t say a monkey. ’Cause you’re both Welsh, let’s call it a sheep. Can you handle a sheep?’

‘How much is a sheep exactly?’

‘Oh, that’s very generous! A hundred it is …’

What appalling behaviour.

While at Radio Wales I became friendly with the teams on the various programmes I was involved with. My producer on

Bank Raid

, Tessa, had a younger sister who would come to stay with her at weekends. Martina and I first met in a pub on Queen Street that she and Tessa would frequent when she was in Cardiff. In those days, the Vaults was a smoky kind of place. On this night in question I had a cold, and was sitting there at the table amongst our crowd of friends feeling a little withdrawn and detached. In an echo of my first meeting with Jacque – although without, this time, the presence of even a solitary Chuckle Brother – Martina and I talked and talked and talked.

When she came back down to Cardiff a few weekends later, I contrived to muscle in on things and just happen to be around her. This second meeting prompted us to begin a correspondence, on paper of course (email was still the stuff of

Star Trek

), in which I would send her Opal Fruits and, eventually, in a more provocative gesture, a single Rolo. Younger readers will be blind to the significance of such a bold, sensual act – unaware, as they undoubtedly will be, of the advertising campaign of the late eighties in which viewers were asked to consider whether they loved anyone enough to give them their last Rolo.

The letters became more frequent and I began to search for a reason to find myself in London, where Martina was working at the time, so that I might be able to say, ‘I just happen to be in the area, shall I drop in?’ The opportunity arose thanks to the Brit Awards when the radio show I was hosting on a Saturday morning managed to get a ticket to the event, held that year at the Royal Albert Hall. I went up on the train, feeling very important indeed. The ticket had come via a record company and I wondered how close to the stage I’d find myself. As it was a record company ticket, I imagined my seat would be rather well placed, right in the thick of it. As it turned out, I was way up high – about as far away from the stage as it was possible to be while still remaining in the building. As the crow flies in a straight line, some of the surrounding houses were closer to the stage than I was.

Noel Edmonds hosted, and there were live performances from The Who and the Bee Gees. But all I could think about was the fact that, once the show was over, I was heading to Fulham to see Martina at the house where she was working as a nanny. In the end, my excitement at the prospect of romance won out over the excitement of being in the presence of Barry, Robin, Maurice et al. I slipped away early, got into a taxi and headed over to Fulham. Just as in my first digs in Cardiff, Martina had a room at the top of the house, although this was a slightly posher, very Fulham house. One of her employers was a Right Honourable; I took against them on hearing that, when the new baby was six weeks old, the parents went to the West Indies for two weeks, leaving Martina with the three-year-old and the newborn with a maternity nurse. They didn’t phone home once.

This wasn’t on my mind as I wove through the London streets in the back of a black cab before slipping into the house and up to the top floor in blatant disregard of the ‘no gentlemen callers’ rule. Two hours and one kiss later, I was back at the Regent Palace Hotel in Piccadilly. I went to sleep in complete ignorance of the fact that I had just kissed my future wife.

The next day I had returned to Radio Wales, and was regaling Rhys with my exciting news – although, to him, seeing Noel Edmonds in the flesh was not that big a deal. I was soon heading up the motorway at every opportunity, excited both at the prospect of seeing Martina and at the added bonus of getting to hear Radio One in FM. I remember in these pre-satellite-navigation days getting lost in the traffic around Fulham; the sun is shining, and Aztec Camera are singing ‘Somewhere in My Heart’.

Martina’s visits to Cardiff became more frequent, and after a time she moved into my little house by the roundabout in Llandaff.

I was coasting along nicely when my time with the station came to an abrupt and rather ungainly end. A new boss was announced and, in the manner of all new bosses, this one wanted to make some changes. I had known Megan Emery a little already; she was the wife of Chris Stuart, long-time host of the breakfast news show on the channel and sometime Radio Two presenter. When she took over at the top, everyone was a little nervous with regard to the security of their position. In his capacity as producer of my show, Rhys went off to meet her for a chat about the future. He breezed back into our office twenty minutes later and uttered the words that still make us laugh, ‘Rob, you’re safe.’

Within a week Megan told me that my contract was not being renewed. She did, however – and this has foxed me every day since she said it – ask if I would like to make a documentary about lawns. Well, I wasn’t happy. I took it very personally. I had a month or so of shows left to run and I’m ashamed to say that my anger got the better of me one Saturday morning when talking on air to a caller whose words were being obscured by the sound of a dog yapping in the background.

‘Sorry, Rob, that’s our dog.’

‘Oh, really. What’s it called?’

‘She’s called Megan.’

‘Really? We’ve got a bitch called Megan here too.’

I know. Unbelievable. She didn’t deserve that.

And off I went, never to return – until Megan eventually moved on, and a new editor took her place.

12

Within a few months of leaving Radio Wales, I was running out of money. I put my car up for sale, a brand-new VW Polo bought a year or so earlier from the Volkswagen garage in Swansea where Dad was working. I went to meet a man at Red Dragon, the local independent radio station, handing him my demo reel and trying to appear simultaneously nonchalant and keen. It came to nothing. I was sending off dozens of letters in response to programmes mentioned in the

Guardian

’s ‘Media’ section. (I still have a ring binder full of rejections. Perhaps they form part of the e-book – press the screen and see what happens.)

Eventually I wandered across the corridor at the BBC to the Continuity Department and managed to wangle a try-out as a continuity announcer. This job basically involved getting up at five o’clock in the morning, sitting in a darkened room surrounded by television screens and waiting until the time came to say, ‘Now the news where you are …’ Or, more excitingly, ‘Let’s catch up with goings-on in Ramsay Street … It’s

Neighbours

.’

The announcer was also responsible for the technical side of things – opting in and out of what was being broadcast on the national BBC network, and making sure that the people of Wales got the Welsh news and not the latest happenings in Bristol and the West. This was the very mistake I made on one occasion, just towards the end of my shift. I slunk out of the building like a murderer trying to leave the scene of the crime undetected, although deep inside I felt I’d done us all a favour. The Bristol news was likely to be considerably sunnier than the Welsh – which, in those days, I would have considered to be rainswept and concerned primarily with redundancy and illness.

This may have said more about me than about the state of the nation.

I began to work continuity shifts quite regularly on a freelance basis and was ready to sign a longer-term contract when the phone rang one afternoon. I was in bed recovering from a strenuous morning’s announcements. It was my agent – my first-ever agent, Siân Trenberth, of Siân-Lucy Management – calling to tell me that I had an audition for a job in London. London! This was exciting. London was the Promised Land, the land of opportunities, the gateway to proper presenting work. Or even to some acting work.

What would this audition be for?

Theatre, television, maybe even a film?

It was none of the above.

Siân explained that there was a new venture starting up on the recently launched Sky TV, called the Satellite Shop. It was home shopping, as glimpsed occasionally on the kind of programmes Clive James used to host, where viewers were encouraged to laugh at some of the idiotic shows that had made their way onto the airwaves in America but which we Brits were far too smart to fall for. My initial disappointment soon gave way to excitement at the prospect of auditioning in London and the belief that the job, were I to get it, would at least be a job in London. It would be a job in TV, and it could be the first step towards bigger and better things.

I took the train to London and went to audition in a building just behind Oxford Street. The would-be sales people were set the task of talking to camera and selling a few items handed to them by the production team just minutes earlier. Then, just when they thought it was over, they were asked to sell anything that came to mind. Determined not to be thrown by this, I calmly took off my shoes and began to sell my socks. ‘Well, if you’re looking for something special between your foot and your shoe, you’ve come to the right place …’ I made an exemplary job of spontaneous sock-selling and, within a few days, was given the joyous news that the job was mine. This was an instant fix on the money front; I went from £30 a day as a continuity announcer to £150 a day as a proud ambassador of home shopping.