Small Man in a Book (23 page)

Read Small Man in a Book Online

Authors: Rob Brydon

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

If we’re going to talk about anxiety, I should tell you that all through my broadcasting years I would suffer the radio equivalent of the classic actor’s nightmare where he or she is struggling to reach the stage and can hear their cue being delivered in the distance. Or they arrive onstage in the wrong costume. Or they don’t know the play they are meant to be appearing in. I’ve subsequently enjoyed the delights of all these types of an actor’s nightmares since working onstage with my stand-up tours. Back in my radio days a good night’s sleep would often be hijacked by vivid images of me sitting in front of the mixing desk, a turntable at each side of me, as I frantically searched the programme box in vain, unable to find the next record. Scarier still was the one where I had the record in my hands but couldn’t cue it up as the turntable was on fire. Meanwhile, on the other turntable, the needle was the dreaded three-quarters of the way across the disc.

These anxieties aside, I suppose I settled into radio pretty well. I bought my first house, on a new estate just minutes away from the BBC, a little two-bedroom starter home for the colossal price of £28,000. I felt like I was Elvis, taking hold of the keys to Graceland. This house taught me my first lesson in not believing everything an advertiser tells you. When walking around the show home, unless someone has told you otherwise, it’s perfectly reasonable to look at the furnishings and take them at face value. Yes, this room really is big enough for a double bed

and

a chest of drawers. No, my friend, look closer. See how that double bed

looks

like a double bed, in many ways it

is

a double bed, but on closer inspection it’s a pretty damn small double bed. If you’re being generous, you might call it a huge single bed, the furniture equivalent of Al Pacino in

Dick Tracy

, where he played ‘Big Boy’ Caprice, the world’s tallest dwarf. And that chest of drawers, you’re right, is just that little bit smaller than a chest of drawers should really be.

But hey, it was a house, it was mine. And, as far as I could see, there were no slugs.

Jacque and I were together through these early days at the BBC, and we would get on the train on a Sunday and head home to Neath for lunch with Mum, Dad and Pete. I delighted in showing her parts of Wales: the Brecon Beacons, the Gower Peninsula and, closer to home, the Aberdulais Falls. We once went for a walk along the canal and found what I thought was a clearing, where we began to enjoy each other’s company in a particularly enthusiastic manner. On reflection, I should have realized that it was a very long and narrow clearing; I suppose some people would call it a path. Certainly the man who came walking along it towards us would have done. The two of us ran, clothes in hand, away from the poor Welsh walker who probably still tells the story of the day he stumbled upon two lovebirds on the bank of the canal.

I went to Scotland for the first of several trips to meet and stay with Jacque’s large family. It seems curious to me now that in honour of the visit – in essence, the first time I would meet the parents of a girlfriend – I bought some slip-on leather shoes to replace the trainers I normally wore. It was a mark of respect, I suppose, a desire to create a good impression. The family lived in Jacque’s childhood home, a big double-fronted sandstone Edwardian house in the Pollokshields area of Glasgow. It seemed to me to be some kind of rambling manor house and was home to a variety of family members. There were her mother and father of course, as well as her brothers Andrew, John, Simon and Patrick. Aunty Eileen had a room on the ground floor and Uncle Michael, the priest, was an occasional resident with his own room on the first floor.

I got on especially well with Simon and Patrick, who were both on my wavelength when it came to humour. As I recall, Simon was a fellow enthusiast for the cinematic musings of my hero Sylvester Stallone. Indeed, it was in Glasgow and with Jacque that I went to see

Rambo: First Blood Part II

, having queued round the block to get in. I’d like to tell you that I considered it inferior to

First Blood

and indicative of a general decline in Mr Stallone’s output. But I can’t. I loved it.

Jacque’s brother Patrick was great, with a superb dry wit. He had been born with arthrogryposis, a congenital disorder that had left him with a curvature of the spine, and so he moved around the house in an electric wheelchair. There was no trace of the ‘Does he take sugar?’ syndrome here, though, thanks to his lovely self-effacing but also stinging wit. As he was transferred into or out of his chair, he would cry, ‘Dignity! Always dignity!’ (This was a quote from Gene Kelly’s character in

Singin’ in the Rain

who, having found fame and fortune, then glosses over his slightly dubious past with the cry of, ‘Dignity!’) This derived from the many occasions when Patrick was left rather undignified – perhaps shoved in a luggage rack when his wheelchair was attended to, or being manhandled by a taxi driver. He and his brothers greatly enjoyed the evening when we all sat down to dinner and somehow Jacque’s polite Welsh boyfriend managed to sit on his food, the plate having mysteriously found its way on to his chair.

I think it was on that same weekend that Jacque and I cunningly decided to spend the Friday night together at a hotel in Glasgow before I would arrive at the house on the Saturday morning, claiming to have travelled up the night before on the sleeper train. Jacque’s absence was explained by her having attended a friend’s party and slept over there. Her brothers were of course aware of the scam, and greatly enjoyed almost letting the cat out of the bag at dinner.

‘So, Rob, you look a bit tired. Were you up all night on that train?’

‘Well, I was a bit, yes …’

‘It must have been hard to get your head down?’

‘Well, no, I managed to in the end …’

‘I suppose the train, it just keeps going all night, does it?’

‘You could say that, yes.’

If Jacque’s parents were aware of our transgressions, they didn’t let on (though I suspect they were far more knowing than I realized). As was always the case, I got on splendidly with Mr and Mrs Gilbride and looked forward to welcoming Kathleen to Cardiff when she came down to Wales to see her daughter in a play. This would also be the setting for her first meeting with my parents.

The play was

The Hard Man

and took place at the Sherman Theatre, scene of my tiny roles with the National Youth Theatre of Wales. It concerned the story of the infamous Jimmy Boyle and much, if not all, of the action was confined to his prison cell. Jacque played his wife and – much to my alarm, dismay and embarrassment – on the occasion of my parents meeting Jacque’s mum for the first time (with me sitting between them in the darkness of the auditorium), we witnessed the lovely spectacle of the lead actor stripping naked and indulging in what can only be described as an enthusiastic dirty protest. He slapped his hopefully substitute doo-doo around the walls of his cell with gusto, like Rolf Harris in the grip of a breakdown. My poor parents. Jacque’s poor mum. We went out for a meal after the play; it was very nice, though as I recall, when it came to dessert, we skipped the chocolate.

Jacque was my first girlfriend, and first girlfriends are only around for so long. We split, saying that the parting was only for a while. She was struggling to find acting work in Cardiff and I was thinking that I was settling down too soon. She sensed that I was getting a bit twitchy, and her older head was wise enough to be the one to say that we should break up for a while and then see what happened. Although it was what I wanted, I was still broken-hearted as I drove away from Euston station after putting her on the train back to Glasgow and her old life.

We hooked up again six months later to go on holiday to Spain with her brother Simon and his in-laws. But on our return, we called it a day.

Meanwhile, my six or seven years at BBC Wales had begun. It’s a period in my life about which I’ve often been a little dismissive whenever asked how I began my circuitous route to here. I have to say that, at the time, I enjoyed it for the most part very much. I did a huge amount of work on a wide variety of shows, both radio and TV. As a presenter I hosted radio shows at various points of the day and week; I also worked on radio as an actor, usually in sketches that called for a range of voices and impressions. On TV I hosted the aforementioned quiz show

Invasion

: two teams competing to win county-sized chunks of a large flashing map, hindered only by my appalling pronunciation of many of the Welsh place names. There was one in particular that I struggled with.

Have a go yourself, see how you fare … Glyndyfrdwy.

Quite.

Even the most cunning linguist would surely have to concede that the word represents a challenge. Time and again I pronounced it Glyn Duvrudwee, much to the visible annoyance of the fluently Welsh-speaking floor manager, when I should of course have been saying Glyn Duverdoy. If you’d like to see this humiliation for yourself, and have had the foresight to purchase the electronic version of this book, then press here now and enjoy my rolled-up, blouson-jacket-sleeved embarrassment at your leisure.

My problem with the Welsh language was that I’d never managed to get to grips with it at school (where learning it was compulsory), and at home it had always had dreadfully dull associations. Whereas now I think it is something to be celebrated and hung on to – so obviously a vital part of our cultural identity – back then it was the language spoken on the news programme in Wales shown in place of

Batman

or some such glamorous TV show. To have grown up an English-speaking Welsh child in Wales in the 1970s was to know the befuddled agony of staring at the screen as the continuity announcer declared, ‘Now on BBC1

Batman

/

Star Trek

/

Land of the Giants

, except for viewers in Wales …’ and a newsreader began, in his native tongue, bringing us up to speed with the latest developments in our homeland (a high proportion of which seemed to feature reporters in rainswept fields addressing the camera as a herd of cows lolled around behind them).

Missing

Batman

was a body blow. It seemed, on the rare occasions that I did get to see it, to be impossibly colourful and glamorous, a world away from a cold wet field just outside Carmarthen. I went through a period of becoming fixated on the show, dreaming of one day owning a house with a study in which a bookcase would slide back to reveal two poles, down which I could slide to my hideout. Hiding was a recurring theme during my childhood, with a dream I kept having in which I sat concealed in a small submarine, possibly yellow, parked on the grass at Woodside. From inside my vessel I could see what was going on around me via the periscope, while I remained invisible. This was a most agreeable state. With the benefit of hindsight, my fixating on poles and submarines seems worryingly Freudian. Let’s move on.

Alongside

Invasion

I played a few odd comedy characters on a pop-culture youth show called

Juice

, became a roving reporter on a Sunday-morning magazine programme,

See You Sunday

, and made an ill-fated cinema commercial for a local jewellery firm. All this was going on while I noticed contemporaries of mine from college begin to make progress as actors. Several of my friends found work at varying levels, but it was only two who achieved what I’d call real success on a large and noticeable scale: Dougray and Hugo Blick. Dougray found theatre and television work with quite indecent haste, while Hugo bagged the role of the young Joker in Tim Burton’s wonderful though pole-free

Batman

.

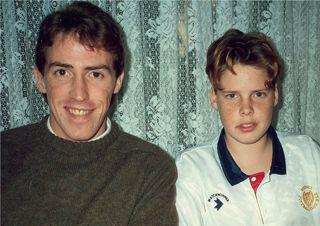

At home with Pete.

‘That was easier than I expected.’ Flying a helicopter on

See You Sunday

During my time at Radio Wales, I spent a couple of years on the early show, and several on a Saturday-morning youth programme, which I absolutely loved doing but hated listening back to (I sounded like such a buffoon). It was a laugh though. I was earning money and living an easy life with little responsibility, breezing in and out of the BBC at my leisure and, in the process, building friendships that would last for years. I became very friendly with Mark Wordley, for whom I’d originally stood in on

Bank Raid

. He continued to present and produce shows at the station and was responsible for my first TV presenting role on

Invasion

, which he produced. I also at this time met the man who was to become my best friend, Rhys John.