Starcrossed (53 page)

Authors: Elizabeth C. Bunce

Yeris Volbann

: Port city on Llyvraneth’s northwest coast.

Yselle

: Housekeeper at Bryn Shaer, native to Corlesanne.

Zet

: Goddess of war and the hunt. Her symbol is the arrow. Patron of the nobility.

Under threat of torture, I am forced to reveal the names of the following individuals who provided aid, comfort, and material support at various times during the creation of this novel:

Rebel agent Erin Murphy, for never letting a client be left in the cold.

Handler extraordinaire Cheryl Klein, for heroic editing under the most harrowing conditions.

Local and long-distance allies Laura Manivong, Barb Stuber, Sarah Clark, Katie Speck, Jo Whittemore, and Rose Green. And particularly the Cleaner, Diane Bailey.

Scott McKuen, for information regarding the nature and behavior of moons.

Bruce Bradley of the Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering & Technology Rare Books Room, for information on Renaissance-era bookbinding, blank books, and handwritten journals.

And my husband, Chris Bunce, who thankfully cannot be made to testify against me.

DIGGER’S NEXT ADVENTURES

IN

LIAR’S MOON

KEEP YOUR HEAD DOWN

I’d have gotten away if that little guard hadn’t cracked me in the eye. His elbow hit me sharp against my cheekbone and sent me reeling. I stumbled backward, blinded, straight into the waiting arms of his partner. The captain.

An arm clamped around my neck and I couldn’t pull away. Squirming in his grip, I kicked out and promptly had my legs seized by the little one and a third man, who hoisted me high between them. One of them whipped out a rope and had my feet tied together before I had a chance to struggle. I opened my mouth to scream, and the captain shoved a filthy rag in my mouth. I gagged, and the men laughed.

“Got her. Easy night’s work. Let’s get our goods delivered and get home to our wives.” The captain twisted hard on my arms until my whole body shrieked with pain. All I could see was his leering face, swimming above me as he swung me easily over his shoulder. I fought back nausea as we bounced along; the last thing I needed was to choke to death on my own vomit before I managed to learn what was happening to me.

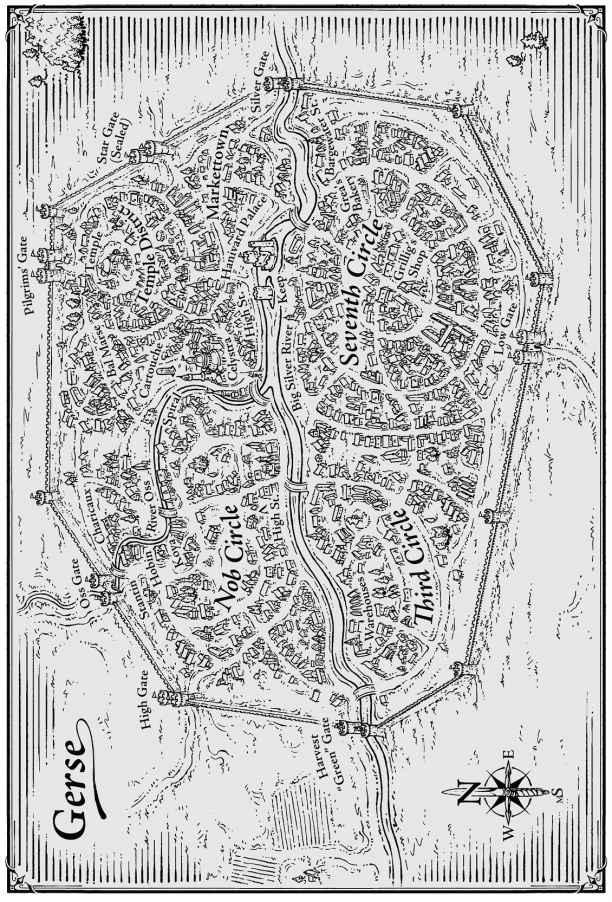

It had been a normal night, more or less. I’d dodged the curfew and set up my patch on the riverfront, near some of the seedier taverns belching out their night’s clientele of drunken merchants’ sons and slumming nobs. Their purses were emptier this late at night, but pickings were easier with them well lubricated. Nobody would get rich off scrum like that, but I couldn’t afford to be picky these days.

Shadows gathered beneath the unlit flamboys; the city had stopped paying to light our less prosperous neighborhoods. I was settling into the darkness when three dark figures melted out of the alley and strolled past me, the wrong direction to have come from one of the bars.

I heard a voice say, “That’s her,” and didn’t even think to be nervous.

Until the blackjack hit me squarely in the back and sent me facedown into the gutter. For a moment I was too stunned to move, just lay there, breathless, the voice echoing in my brain, all wrong.

That’s her.

That’s

her.

Not

him

— and I was dressed in men’s clothes, filthy trunk hose with a ridiculous codpiece, my hair tucked up in an oversized cap. There was nothing feminine about me. Oh, hells.

I scrambled to my feet and spun around. Three of them, in red uniforms. This was not a fight I could win. Still, I dodged and swung out hard, catching the middle guy in the gut. I shoved him into the biggest one, the one with the gold badge on his chest and the blackjack swinging casually from his meaty fist. I turned to run — and that’s when the little one came out of nowhere and clipped me in the eye.

We trotted along at a pretty good pace, but I couldn’t track our location, not with the world lurching past upside down. Gray cobbles, dark pinkish cobbles, gray again — oh, very useful. I craned my neck to see if I could recognize the footings of any buildings and nearly passed out from dizziness.

“Keep your head down, thief.” And as if I needed help with that, a stinking hand shoved me hard in the face.

“Easy there. We don’t get paid extra for bruises.”

For some reason, that sounded notable, but the blood rushing through my brain made it hard to focus. How had they found me? Why? I thought I’d been careful, but maybe they’d finally tracked me down, linked me to the rebels.

But the Night Watch didn’t bother Sarists and magic users. Even through the roar of blood in my head, something about this didn’t make sense.

The captain came to an abrupt stop, swinging me partly around as he turned. I caught a glimpse of pale stone wall, nearly white in the waning moonslight, and an impossibly tidy flagstone walkway, and I felt every aching muscle in my body tighten.

This wasn’t the Cages, the city gaol. And, of all the stupidity — these weren’t Watchmen. Red-and-gold livery meant

royal

guards, and the high white wall topped with its iron spikes and shattered glass was the Keep. The king’s prisons.

“Mmmph!” I struggled then, flailing at the captain with my feet and bound hands.

“That’s enough of that,” one of the others said, and clapped me hard on the side of the head. The captain shucked me off his shoulder and plucked out the gag, and I stood, wavering, just inside the ironbound gatehouse of the Keep. A bristly, one-eyed guard pawed at me, turning my head to look under my chin, patting at my legs and chest. For weapons, I hoped. His grimy fingers lingered too long against my throat, and I slapped his hands away with my bound ones.

“Boy’s a fighter, then,” the guard said. “He’ll be popular with them nobs.”

Well, at least my disguise had worked on

somebody

.

“What is this?” I demanded. “Why are you arresting me?” Though

kidnapping

might have been more accurate.

The guard shrugged and flipped through a battered ledger book. “Take it up with the magistrate at your trial date.”

“No!” My voice verged on panic. “Let me go — I haven’t done anything!”

But the guard had turned away to the rear of the gatehouse, where he now worked a massive hand-crank set into the stone wall. From above came an ungodly screech and clank of metal on wood; at our feet, the splash and ripple of ink-dark water. The Keep sat on an island in the middle of the Llyd Tsairn, the Big Silver river, a bowshot from the king’s royal palace. The only access was by way of a drawbridge mounted on the opposite bank and operated from the guardhouse. Or on the coroner’s barge, sailing out from the executioner’s block.

The red guards who’d nabbed me lingered outside the gatehouse, as the captain emptied out a purse among his fellows. I frowned, but the bridge slammed down with a shudder that shook the whole gatehouse and drew my attention elsewhere. The maw of the Keep doorway across the river gaped black in the distance as two more guards in royal livery stepped onto the bridge, an iron chain swinging between them. Smoky torches made long shadows on the narrow wooden planks. The gatekeeper hauled up the gate and gave me a little nudge toward the landing.

“Get on, then, boy,” he said. “No way out now but over.” The iron bars crashed down behind me once again. I felt cold all through. Everyone knew the trial was a fairy tale; people thrown to the Keep waited months or years for a magistrate’s appearance that might never come. The guards crossed over the river in practiced, easy strides, and just when I’d more or less decided to take my chances with the Big Silver — not that I could swim with my hands bound — they shoved me before them onto the narrow, railing-less bridge.

I cast one last glance at the water behind me as they pulled me through the prison gates.

“That’s two marks,” the guard at the gate said to me. They charged for

everything

in the gaols, including, it seemed, the privilege to be dragged off to your cell.

I lifted my chin and glared at him. “Bite me,” I said, and another heavy fist clapped into my head.

They led me through a twisting knot of noisy corridors obviously designed to upset one’s sense of direction. But I kept my eyes open, counting the turns and staircases and committing them to memory. After a long, spiral stair winding up the core of the tower, the guards let me out onto the top floor of the Keep. Sallow torchlight flickered wanly, illuminating a long, gloomy passage lined with sturdy, ironbound doors, one tiny, barred window set high in the wall at the very end letting in the ghost of the moonslight.

My guard stopped before a cell and banged on the door. “Your

lordship

,” he called, and I could hear the sneer in his voice, “someone’s sent you a present

.

Quite a pretty lad this time.” A finger stroked along my ear, and it took all my restraint not to bite him. He heaved the door open, and I stumbled forward, pitching headlong into the cell and landing hard on my knees. The door clanged shut behind me. Scuffling through the filthy rushes, I got my back against a wall and set about trying to wriggle out of my bonds.

“Damn it.” I heard a soft voice from the dark recesses of the cell. “This stopped being amusing several days ago.” Another sound — quick and light, a flint striking — and the cell wavered into a faint, sickly glow. I blinked and reached instinctively for any weapon, but they’d taken my knife and there wasn’t anything else at hand.

“Stop right there,” I said, but I didn’t sound terribly convincing.

“Look, I’m not going to hurt you,” said a tired voice, and my cell mate stepped forward, bending low over me. “They’ll get tired of the game eventually and move you down a level, so you’d better enjoy yourself while you’re up here. There’s fresh water — well, relatively fresh, anyway — on the table.”

I stayed where I was, my thoughts tumbling. My companion —

your lordship

, my guard had called him; a nob, maybe? — crouched before me. He didn’t look much like a nob, in his torn shirt and no doublet, with unshaven cheeks and a fading bruise under one eye, but he held out his hand.

My head pounded brutally, and I felt disoriented. In my confusion, my cell mate looked almost familiar.

“That’s a nasty gash,” he said, reaching for my face. I knocked his grubby hand away. “Easy,” he said. “I won’t hurt you, but you need to relax so I can see what they’ve done to you. You must have put up quite a fight; they don’t usually come in quite so . . . used up. Here, sit up into the light.”

Warily I let him draw me forward to a plain frame table and benches in the middle of the cell. Something about the smooth curve of his jaw, the bend of his neck as he leaned over me . . . I winced, trying to shake my head.

“What’s your name?” he said.

I paused, considering. Who should I be this time? Maybe I could play this — and my wealthy cell mate — to my advantage. Boy or girl? Would tears help? I sat forward and pulled off my hat, letting my braided hair, coiled round my head, show I was a girl.

“I don’t believe it.” My companion held up the candle. “Am I delirious?”