Stonehenge a New Understanding (12 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

Realizing that a single episode of plowing into the Neolithic ground surface would have virtually destroyed these house floors, we now understood just why so few Neolithic houses have ever been found in England.

Over the next few weeks, we found traces of another four houses within the trench; we knew we couldn’t rush this and would need more time in future summers to excavate each of them to the highest standard possible. Having spent the best part of two decades excavating prehistoric house floors, Colin and I had developed new methods for studying them. As a student I’d listened to an experimental archaeologist, Peter Reynolds, tell us about his reconstruction of an Iron Age roundhouse.

1

He’d suggested that the evidence in such houses is so minuscule that archaeologists should dig with teaspoons, not trowels and mattocks, in order to understand how they were lived in. I had roared with laughter at the time: This seemed a preposterously obsessive and time-consuming thing to do.

Years later, though, as I dug my first house floor in the Outer Hebrides, I realized he was very nearly right. I was working with some very talented environmental archaeologists, Helen Smith and Jacqui Mulville, and we worked out that the micro-debris and chemical residues accumulated on the floor during the house’s occupation could tell us a lot about daily domestic tasks and where they were performed—but it was going to be a major job to retrieve the evidence.

Archaeologists can pick larger finds out of the ground they’re working on—those things easily visible in the soil—but it’s usual practice to use a 10-millimeter sieve on site (about the mesh size of a normal garden sieve) to ensure nothing gets missed. Smaller sieves are pretty useless because the soil clogs the mesh so quickly. To retrieve anything smaller than 10 millimeters in diameter, we need to wet-sieve the soil: to wash it through sieve mesh of various sizes in a system of water tanks. It’s a long and dirty job, as the soil from each context has to be bagged up in sacks, labeled in minute detail, and usually taken away from the excavation site to a wet-sieving team working in an area with an ample water supply. It slows down the excavation process enormously, but the results are worth the effort.

The remains of four Late Neolithic houses are visible in this main trench at Durrington Walls. I am standing outside the doorway of one of the houses in an area of midden (heaps of domestic rubbish).

In South Uist we’d carefully wet-sieved the entire occupation layer on top of the floor of a Bronze Age house, which was excavated in half-meter squares. Using a mesh size of just two millimeters, we’d retrieved minute fragments of animal bone, potshards, burned plant remains, and broken artifacts, and were able to identify the areas of the house where

cooking and various types of craft-working were carried out. We also took hundreds of small soil samples from the floor, to plot concentrations of chemical elements, such as phosphorus and nitrogen, and many further samples to send to a soil micromorphologist. Micromorphology is a technique of examining sections through the soil under a microscope to establish how the floor layers were formed, of what they were composed, and whether later floors were laid on top of earlier floors.

The Durrington Walls houses needed us to apply these well-honed techniques once again. We knew we had to sample the whole floor of each house in minute detail. We dreaded doing it—we knew how long it would take and how many sacks of soil we’d have to heave back and forth—but we knew the results would make it worthwhile.

Unlike the Hebridean house floors of soft peat and sand, the Durrington floor surfaces were comprised of fairly hard chalk plaster. Every time the Neolithic inhabitants had given their house a good sweeping, they’d sent much of the micro-debris of their lives straight out of the door, so it was more difficult for us to reconstruct activity patterns than it had been on the Scottish sites. Nonetheless, the thin ash layer across the floor gave us a moment frozen in time: the moment of the house’s abandonment. And, as we were to discover later on, the floors held other clues to unraveling the secrets of Neolithic daily life.

The houses were built on a slope but had level floors. This had been achieved by terracing the hillside, stripping the turf from higher up and laying it in a band lower down. Houses higher up were cut into the bare soil while those lower down the slope sat on a leveled platform of turf. This showed an element of organization and planning that went beyond that of the household. Perhaps this new settlement was larger and more organized than we’d at first expected.

This was not the first time that people had lived here. Buried in the turf were flints, including a leaf-shaped arrowhead, indicating that early farmers had lived here at some point during the fourth millennium BC, at least 500–1000 years before the houses were built.

At the bottom of the slope, within the valley that leads from the interior of the henge toward the river, we finally uncovered what we’d set out to find. By extending our excavation trench twenty meters upslope from the eroded area where we’d dug in the valley bottom in 2004, we

discovered that a meter-deep layer of colluvium (soil, loosened by plowing, that had washed down from higher up the valley) had settled on top of—and hence protected—the prehistoric ground surface. This surface was a thin layer of remnant turf and topsoil that covered a flat road surface of packed and broken flints. As the roadway had gone out of use, so grass and weeds had sprung up, eventually creating a thin layer of humus worked into soil over decades by earthworms. Carefully plotting the finds within the prehistoric turf layer covering the road, we discovered that this soil had accumulated over several centuries. Mixed in with the oblique arrowheads and Grooved Ware of the Neolithic were the later styles of barbed-and-tanged arrowheads, and pieces of distinctive Beaker pottery from the Early Bronze Age, indicating that there had been activity here long after the Neolithic houses had been abandoned.

Our theory was right—there was an avenue running from Durrington Walls to the river, an avenue so wide that our trench was not big enough for us to see the full width of this Neolithic roadway. In 2005 we found its northern edge, defined by a low chalk bank about five meters wide, and in 2006 we found the parallel bank running along the south side. The flint road surface was 15 meters wide and, in its entirety, the avenue was 30 meters (100 feet) across from the outer edges of its parallel banks. It dwarfs the modern road built in 1968 through the middle of Durrington Walls: That has a roadway only 10 meters wide.

The Neolithic road surface was constructed from hard-packed, natural, broken flint, but it also contained lots of animal bones, pieces of burned and worked flint, and even potshards that had been incorporated when the road’s matrix was laid down. These bits of rubbish mixed into the road construction meant that people were already living here before the surface was laid.

When we stripped off part of the upper surface of the road, we found a lower layer of flints that contained no artifacts at all. Mike Allen and fellow soil specialist Charly French reckoned that this basal deposit was formed by natural agency, a geological deposit of coombe (valley) rock. Before the Neolithic, the bare valley floor had become covered with broken flint eroding out of the valley sides. This natural feature had been exploited and remade by the Neolithic inhabitants of Durrington Walls.

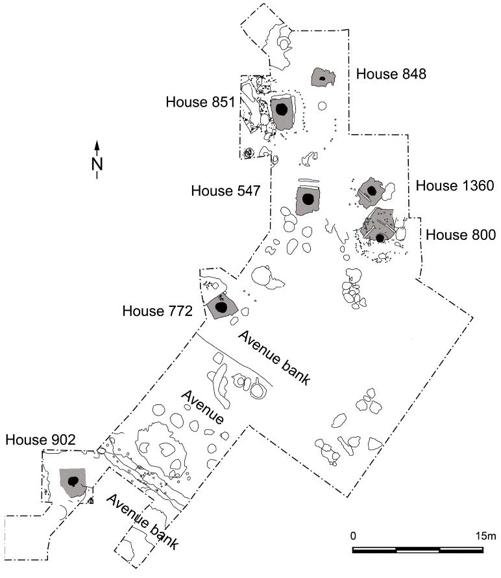

A plan of the main excavation at Durrington Walls showing the plaster floors of the Neolithic houses (shaded) and their central hearths (black). The other features are pits and stakeholes.

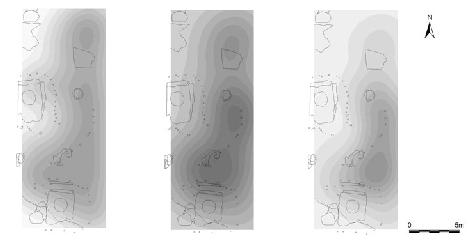

Computer-generated plots showing the relative density in the northern part of the main trench of animal bones (left), worked flints (center) and burned flints (right). The outline plans of the houses are visible, as is the curving line of postholes forming a fence that separated two of the houses.

The avenue had yet more information to give us. Clive Ruggles came to take a good look at the Durrington Avenue while it was being excavated, to record its exact orientation. He found that the avenue’s orientation when looking westward, upslope from the river, was within a degree of the midsummer solstice sunset during the Neolithic. Clive already knew that the Southern Circle inside the henge, partially excavated in 1967, had an entrance facing southeast, to the point at which the sun rose on the midwinter solstice. Since the two directions of midsummer sunset and midwinter sunrise are perpendicular to each other, there is usually no way of being sure whether both directions are significant or only one of them. Our avenue was pretty much aligned with the entrance to the Southern Circle, but was a few degrees off the precise axis of the midwinter sunrise. Which mattered most to the avenue’s builders—was the avenue meant to share the same alignment as the timber circle (toward midwinter sunrise), or was it aligned in the opposite direction, toward midsummer solstice sunset?

Clive worked out that the midsummer solstice sunset was the important direction—the avenue shows a deliberate alignment with the setting sun, not with the axis of the timber circle. He is convinced that the builders made sure that the avenue was a few degrees off the axis of the

Southern Circle so that it would align with the midsummer sunset. As a consequence, it has an imperfect alignment with the midwinter sunrise. Had the avenue been constructed simply to lead from the midwinter sunrise to the Southern Circle, it would have missed the alignment with the midsummer sunset. The midsummer solstice alignment is affected by the topography: The Durrington valley rises quite steeply from southeast

to northwest. The steepness of the valley means that the sun disappears below the horizon sooner than it would on flatter ground, so the avenue is aligned on the spot where the midsummer sun actually sets.

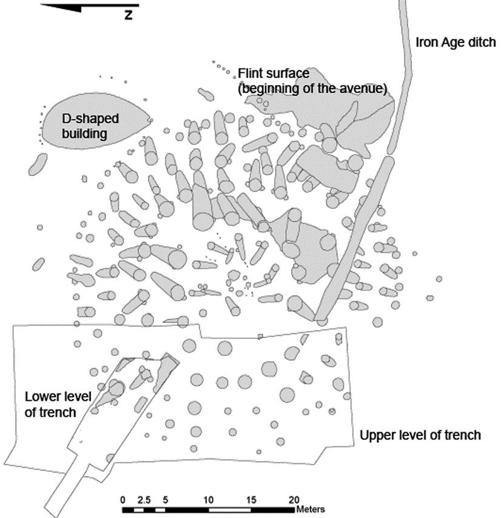

Full plan of the Southern Circle, combining the 1967 and 2005–2006 excavation and geophysics results. The cone shapes are the postholes and their ramps. Julian Thomas’s excavation trench is marked to the west. The rest of the circle is now buried beneath the modern road.