Stonehenge a New Understanding (15 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

Josh was joined by David Robinson, lecturer in archaeology at the University of Central Lancashire—or, as we know him, California Dave. Although his main interest is in the rock art of California, and the hallucinogens taken by Native Americans to attain trance states for making the art, California Dave is also an expert in the British Neolithic. As a student years earlier, he came on an exchange program to Sheffield University and has spent many summers digging for Josh and Julian.

As they dug to the bottom of the holes that Cunnington thought had once held stones, Josh and Cali Dave could see that she had been right. Two enormous sarsens once sat in these holes and had left distinctive layers of crushed chalk at their bases. Furthermore, Cunnington had missed another two stoneholes. These stones had actually formed a three-sided setting, open to the west; a similar stone setting still stands within the Avebury henge, where it is called a “cove.” Four standing stones, probably less than two meters high, had formed this cove at Woodhenge; they were later removed and replaced around 2000 BC by two large sarsens, standing probably more than two meters high. Just where all these stones have gone is a mystery. The last two could have been dragged out and broken up in historical times, but the first four were definitely moved during the Neolithic; perhaps they were taken to Stonehenge or to an unknown spot in Woodhenge’s immediate vicinity.

Excavating one of the postholes at Woodhenge. After the posts had decayed, a “cove” of sarsen standing stones was erected in the southern part of the monument.

It is most likely that the cove at Woodhenge was erected after the wooden posts had decayed. This process of replacing wooden monuments with stone, known as “lithification,” has been noticed by archaeologists on many megalithic sites.

1

Perhaps it represented the process of hardening in which the transient and decaying was replaced by the eternal. At the center of the cove, Josh and Dave discovered a hole left by the roots of a blown-over tree. Potshards and flint blades from its fill were of styles found in the fourth millennium BC, at least five hundred years earlier than Woodhenge’s timber posts, so this tree might have been growing here long before Woodhenge was erected.

Beneath the henge bank, Josh and Dave found that the builders of Woodhenge had stripped away the turf. In doing so, the henge-builders had exposed another such tree-throw hole, which they had capped with a surface of rammed chalk. Within and around this tree hole there was a small heap of shards from a pot. The shape of this pot indicated that it came from the beginning of the Neolithic, around 3800 BC. This pot was dumped here more than a thousand years before Woodhenge was built, at around the same time as the Coneybury pit was filled with feasting debris.

2

Although we could not be sure whether the broken pots

found in the two tree holes at Woodhenge were of the same type, they could well have been deposited around the same time, when the earliest farmers began clearing the few trees standing on the high chalklands.

In the valley below the east entrance to Durrington Walls, we extended our trenches to investigate more houses as well as to obtain a complete cross-section of the new avenue. I’d promised Farmer Stan that this would be the last time we dug up his field but I was hopelessly wrong—it took another year to finish what we’d first started in 2004, far longer than we had expected. Stan wasn’t very pleased (the loose soil of our filled-in trenches was attracting rabbits and creeping thistle into his pasture) but he knew that what we were finding was rewriting the Stonehenge story. It was worth the inconvenience.

On the avenue leading from the henge entrance to the river, we discovered a line of pits that had been dug out and filled with animal bones before the final road surface was laid, arranged on a slightly different alignment to that of the avenue itself. On the north side of the avenue we found a group of three holes that—one after the other—had each held a standing stone. Next to them, large chunks of sarsen from a broken-up stone had been buried in a shallow pit. Smaller pieces of this shattered stone covered the area around, lying on the road surface and buried within the soil that had developed over the next few centuries. It’s unusual to find evidence for destruction of a standing stone in prehistoric times, but here it was. Maybe the stone stood as a single marker along the avenue, in the same way that the Heel Stone stands alone on the Stonehenge Avenue.

3

Alternatively, this was one of a row of stones along the avenue’s north side. In 2004 we’d found the bottom of a similar pit just seven meters away, close to the “phallus pit” within the eroded part of the avenue. Perhaps a line of stones had led to the river.

The number of Neolithic house floors we discovered and excavated rose from five to seven. Five of the houses were terraced down the slope overlooking the avenue. The other two sat opposite each other on the avenue’s low banks, like a pair of entry kiosks. These were particularly odd structures, and not exactly houses. Each had only three walls, lacking the fourth wall facing southeast down the avenue. Each had a central fireplace but there were no traces of the footings for wooden furniture of the sort found in the other houses. They look more like heated Neolithic bus

shelters than real houses. Yet their floors had been carefully maintained and repaired and the southern building had a large midden on its south side. Perhaps they were places where certain people could gather, protected from the rain and the cold, to watch whatever was happening along the avenue, as processions moved up from the riverside toward the Southern Circle and the blazing fire outside its entrance.

The houses on the slope beside the avenue were all slightly different but were built to a similar specification: always square, with a central hearth and a yellow chalk-plaster floor. The largest house was also the most solidly built. Deeply driven stakes had formed a wattle-and-daub wall whose outer face had been surfaced with a mixture of crushed and puddled chalk that would have looked something like pebble-dash. In technical terms, this is not exactly the traditional building material known as “cob,” which is a mix of crushed chalk and cow dung, but it’s close enough. In 2009, I stopped to look at a dilapidated old barn in the nearby village of Winterbourne Stoke. This building had cob walls much the same as those of the Durrington house built more than four thousand years earlier. It seemed extraordinary that some Victorian farmhand had used the same methods and materials as his predecessors 180 generations before.

This large house beside the Durrington avenue had its doorway facing south. Immediately inside the threshold, the plaster floor had been worn away by the comings and goings of many feet. On the left-hand side of the door, in the southwest corner, there was a square storage area, perhaps for coats, bows and arrows, antler picks, and all the things one puts down when coming indoors. Along the west wall were the foundations for a wooden box bed, with another one opposite it along the east wall. Colin had studied exactly the same arrangement in the Neolithic houses in Orkney.

4

Chemical tests there had shown that the area around the bed furthest from the door had higher levels of phosphorous, which has been explained as the result of babies and small children wetting the bed.

Against the north wall of the large house, opposite the doorway, were the foundations of a piece of wooden furniture, narrower than the beds, with two end uprights and another in the center. Thanks to the surviving stone-built Orcadian furniture, we know exactly what this was—a wooden “dresser” formed of two shelves, one on top of the other, and divided into left and right sides. Perhaps this was where the house’s special belongings

were kept, or the clothes and fabrics. At the end of the east bed, tucked into the southeast corner, was another square storage area. The ashy layer left on top of this part of the house when it was abandoned was littered with tiny pieces of broken pottery. The plaster floor in this corner was also heavily stained by ash, no doubt from countless rakings-out of the fire. Here was the kitchen area, and this box in the corner must have once contained cooking items and perhaps food supplies.

To cap it all, we found two knee prints close by, on the south side of the fireplace, where someone had spent long hours kneeling by the fireside, tending the fire and cooking food in flat-bottomed Grooved Ware pots. I initially wondered if these knee prints might actually be footprints, made by someone squatting on their haunches as people do the world over in cultures where there are no chairs or tables—but there is no doubt that these hollows were shaped by a pair of knees. The house floor had been kept fairly clean and the only complete items we found were an arrowhead and a bone pin that had both fallen behind the furniture and escaped whatever served as a Neolithic broom. In the northwest corner of the plaster floor we found two teacup-sized holes full of the tiniest flint flakes and chippings. Perhaps these little dustbins were used to dispose of unwanted splinters that could inflict deep wounds on bare feet.

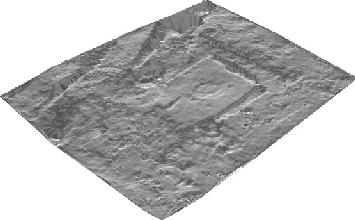

A laser scan of the floor of House 851, showing the beam-slot indentations where wooden furniture once stood around the edge of the plaster floor. To the left of the circular hearth a pair of indentations, made by someone’s knees, are also visible.

Colin and I had seen this exact layout of furniture before, in the largest house at Skara Brae.

5

In fact, you can overlay the internal plan of Skara Brae’s House 7 on the large house at Durrington: They are exactly the same in size, shape and the positions of internal furniture. The only differences are that House 7 was built on a different orientation, its hearth—like all Orcadian hearths—was square and not round, and it had two stone boxes for storing shellfish. But the two houses are more than five hundred miles apart—how can they be so alike?

Although Skara Brae was founded before 3000 BC, House 8 was not built until near the end of the village’s occupation five hundred years later. So the two houses are just about contemporary. Was Durrington Walls built by prehistoric Scots from the Orkney Islands? This is pretty improbable, though the people of the Stonehenge area might have been heavily influenced by fashions that originated in Orkney. It is very likely that Grooved Ware was invented in Scotland, if not in Orkney itself, and then spread southward.

6

It seems not to have been adopted in Wessex until around 2800 BC, four hundred years after it first appeared in Orkney.

Archaeologists have recently uncovered a large settlement in Orkney at the Ness of Brodgar, with hall-like buildings and a thick boundary wall separating it from the Ring of Brodgar, Orkney’s version of Stonehenge. This complex was built before 3000 BC, so it predates Stonehenge and Durrington Walls. Perhaps the remote northern islands spawned a religious and cultural reformation that eventually spread across the whole of Britain. Similar square house plans of this period are known from Wales and eastern England. This was probably the standard form of housing across Britain, replacing the long rectangular houses of the previous millennium and itself to be replaced in the Bronze Age by round houses.

Just northeast of the large house at Durrington was a small house, also rectangular, with a proportionately small fireplace. The door of this little house was probably also south-facing, and the scatter of small chalk lumps around it showed that it had cob walls like the other, but there were no holes for stakes to support the walls. At three meters by two meters this was a tiny building, and the lack of debris on its floor shows that it was a shed or store. This pair of one big and one little house was separated from all the others by a short length of fence, surviving as a

curving line of postholes. It is evident that this was a main house with an ancillary outbuilding, set within their own compound. Turning back to the plan of Skara Brae, we saw that House 7 similarly had its own outbuilding, and that this pair of structures was separated from the other houses by a long passageway. Comparing the plans of the small ancillary structures, we could see that the Scottish outbuilding was virtually identical to the one we were digging in Wiltshire.