Stonehenge a New Understanding (13 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

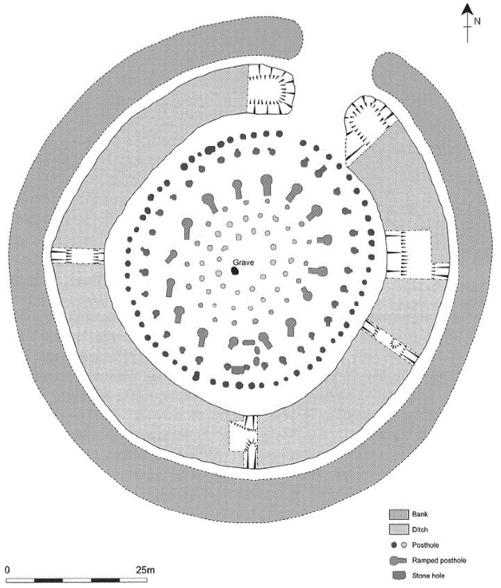

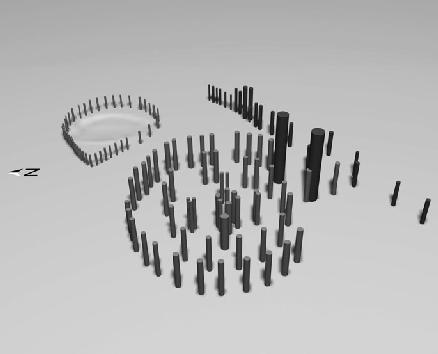

A plan of the Late Neolithic timber circle of Woodhenge. Today the postholes are marked with small concrete pillars and the bank and ditch are barely visible. The contents of the grave were destroyed during the Blitz but the burial is thought to date to the Early Bronze Age.

Ever since Geoff Wainwright’s discovery of the rings of postholes that held the timbers of the Southern and Northern Circles within Durrington Walls, archaeologists have tried to reconstruct what these timber circles looked like. The Northern Circle consisted of one or

perhaps two rings of posts enclosing a rectangular setting of four large posts.

2

This circle was approached from the south (from the direction of the Southern Circle) via a post-lined passage that passed through a façade of posts forming a screen on the south side of the rings of timbers. Geoff tentatively ascribed the outer and less convincing of the two post rings (almost 25 meters across) to a first phase of the structure. Since more than half a meter of chalk had gone from the ground surface here by the twentieth century, when he excavated the site, only the deeper features survived. A four-post square setting in the center of the rings appears to have been oriented eastward, toward the midwinter sunrise.

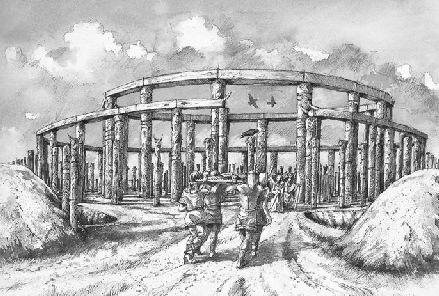

A reconstruction of the timber posts at Woodhenge.

The Southern Circle was much more impressive and better preserved; artifacts lying on the Neolithic ground surface around it were still in position.

3

At its center was a rectangular arrangement of posts enclosing a smaller setting of six posts. Geoff interpreted these posts as belonging to the first phase of construction. They were surrounded by two concentric rings of timbers, and approached from the southeast through a screen of posts.

The timbers of this first phase of the Southern Circle had been left to decay in their holes. When the circle was excavated, the outlines of the rotted timbers survived as “post-pipes,” voids left by the rotted-out wood into which soil had slowly trickled. These posts were around 20 centimeters in diameter, slightly thinner than a telegraph pole. Archaeologists can tell from the soil layers if a pit or posthole has been dug into at some point after its first construction. At the center of the Southern Circle, one of the postholes in the rectangular setting showed that the post had been replaced twice; two others had been replaced just once. On the basis of the likely lifespan of these timber uprights, Geoff estimated that the first phase of use of the Southern Circle lasted a minimum of sixty years.

This first phase was replaced by six concentric circles of posts whose uprights ranged in size from around 20 centimeters to over a meter in diameter; the outermost ring of posts measured almost 39 meters across. Among the largest posts were the two marking the southeast entrance. These posts too had decayed in their holes. Geoff reckoned that these huge posts probably survived for the best part of two hundred years.

All of the Southern Circle’s Phase 2 posts were so large and tall that the builders had to cut ramps into the chalk to feed the end of each post into its hole before heaving it to a vertical position. In 2006,

Time Team

built a replica of the Southern Circle, borrowing twenty soldiers from the Larkhill army barracks to try to raise just one of the smaller-sized posts by muscle power. To everyone’s surprise it was too difficult—they had to resort to twenty-first-century mechanical means to erect it.

In and around the Southern Circle, Geoff found some traces on the surviving Neolithic ground surface of what took place here. A small fireplace was positioned in the center of the circle, and an enormous fire-pit (five meters long) outside the southeast entrance was set into a 15-meter-wide surface of broken flint, adjacent to a platform of chalk blocks. Part of the interior of the circle was surfaced with rammed chalk but otherwise it had no proper floor. On the northeast perimeter of the circle was a post-lined hollow whose shallow filling of pottery, bones, and other rubbish led Geoff to interpret it as a midden.

4

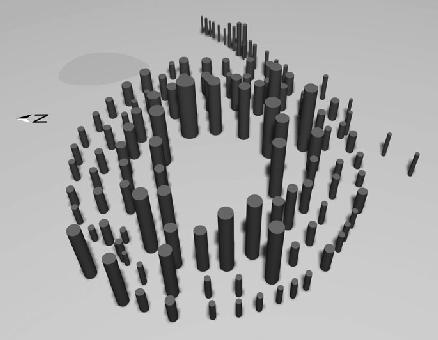

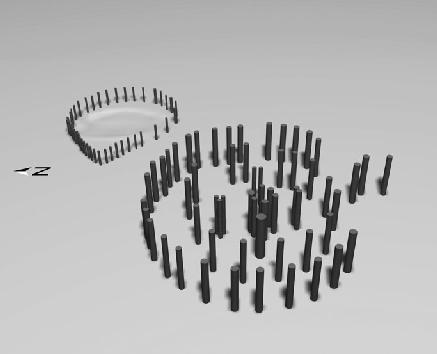

Model of Phase 1 of the Southern Circle as a square-shaped arrangement of posts surrounded by two concentric timber circles, with the D-shaped house to the northeast.

Forty years before Geoff Wainwright went to Durrington Walls, Maud Cunnington had excavated a similar timber circle at Woodhenge, situated on the high ground just south of Durrington Walls, overlooking both the River Avon and the small valley in which the large henge lies.

5

Sitting on top of a ridge and plowed in recent times, Woodhenge’s original ground surface had disappeared long before Cunnington’s excavations. This circular timber monument had also consisted of six concentric arrangements of posts, except these were laid out as ovals rather than true circles. The posts, of similar diameters to those of the Southern Circle, had been left in position to decay. The whole structure was enclosed within a ditch and external bank. Cunnington noticed that the long axis of the ovals was oriented on both the midsummer sunrise and the midwinter sunset, as is also seen at Stonehenge itself. At the center of the timber circles was a cairn of flint nodules, beneath which was the skeleton of a child.

Model of Phase 1/2 of the Southern Circle. In this phase the builders added a timber portal facing the midwinter sunrise.

Cunnington thought that the child had been sacrificed. She noted that its skull was split in two, perhaps by a stone ax. Curiously, there is no mention of this injury in the pathologist’s report on the skeleton—and we can’t go back and re-examine the original bones because they were destroyed during the bombing of London in the Second World War. Josh Pollard has had another look at Cunnington’s records and he thinks that she may have been mistaken:

6

The skull could have collapsed naturally along the bone’s sutures under the pressure of earth from above, rather than being damaged by a deliberate blow. He also thinks that this is a later burial—that the child was not buried here by the Neolithic builders but was added in the Early Bronze Age, when the wooden monument would have been decayed ruins.

These three timber circles pose difficult questions. Were they built at the same time as Stonehenge or were they erected earlier, some sort

of wooden prototype for the ultimate version in stone? Were they roofed? If so, did people live in them? Colin and Julian were also keen to find out more about what was in the postholes—were the animal bones and pottery plain old rubbish, or “structured deposits” of ritual offerings? The question of how these artifacts had fallen into the postholes was also tricky. Geoff had reckoned that the decay of the timbers had created cone-shaped voids (weathering cones) into which material stacked against the posts or lying close to them had fallen. Colin and I were not so sure.

During one of our evenings in the Plume of Feathers in 2003, we’d spent hours looking at the drawings of every posthole from the 1967 excavation. It was a Saturday night and the bar was getting crowded and noisy, so no one seemed to notice us or our Eureka moment. Colin realized that the so-called “weathering cones” were actually pits dug into the tops of the postholes after the wood of the posts had completely decayed. But why should anyone have done this? Why was it so important to dig new pits into old postholes, and there deposit groups of artifacts? Was it something to do with marking change and decay? We really needed to look at some of the postholes that hadn’t been dug out during the 1967 excavation. Geoff’s three-month rescue dig in 1967 had had to stick to the corridor of the proposed new road. Consequently, parts of both timber circles remained unexcavated because their edges lay outside the construction corridor.

The 1967 excavations were spectacular, a watershed in British archaeology. Rarely used before, a fleet of mechanical diggers proved their worth in stripping off soil down to the chalk bedrock across the huge area. The use of diggers was considered frankly scandalous by some archaeologists—Geoff had to put up with vicious criticism—but a new generation realized the value of these machines in terms of allowing archaeologists to open up huge areas to investigate, rather than being confined to small, hand-dug trenches. In retrospect, this was one of the biggest revolutions in modern archaeology.

As the digger machines clawed their way across the interior of Durrington Walls, a team of a hundred laborers and volunteers followed behind, scraping to the top of the bare chalk and revealing the outlines of postholes. Over a long, hot summer, Geoff’s workforce toiled on the baking

chalk to empty out two sections of the henge’s enormous ditches (5.5 meters, or 18 feet deep), and to dig out the postholes of the Southern and Northern Circles. By night, the team slaked their thirst in the nearby Stonehenge Inn, spending their £1-per-day wages on as much beer as they could drink. The excavation took on a legendary significance. This was one of the key digs where Geoff recruited an intensely loyal crew of heavy-drinking, hard-toiling tough guys. Over the next eighteen years, they went wherever Geoff needed them, working in all conditions. By the late 1970s they’d acquired an official name (the Department of the Environment’s Central Excavation Unit) and a fearsome reputation. They were the archaeological equivalent of Hell’s Angels—other teams lived in fear of a social visit from the Central Unit because of the mayhem that would result.