Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (33 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

Leaving Kilise Camii we turn left and then right onto a street that we follow until we come to the rear of the medrese of Ekmekçizade Ahmet Pa

ş

a, which we visited earlier. There we turn left on Kovac

ı

lar Caddesi, which we follow for about 200 metres before returning right on the first through street on the right. This leads through a picturesque arched gateway under the Valens Aqueduct and out onto a large open area on the other side. There we see another former Byzantine church, this one of considerable interest.

KALENDERHANE CAM

İİ

The church was converted into a mosque by Fatih under the name Kalender Hane, since it was used as a tekke by the Kalender dervishes. It was once identified as the Church of St. Mary Diaconissa, more recently as that of St. Saviour Akataleptos, and now, as the result of an archaeological study and restoration by Cecil L. Striker of Dumbarton Oaks and Do

ğ

an Kuban of Istanbul Technical University, as that of the Theotokos (Mother of God) Kyriotissa. The church is cruciform in plan, with deep barrel vaults over the arms of the cross, and a dome with 16 ribs over the centre. It originally had side aisles communicating with the nave, and galleries over the two narthexes. The building has proved to date, not from the ninth century, as was formerly supposed, but to the late twelfth. It still preserves most of its elaborate and beautiful marble revetment, making it one of the most attractive Byzantine buildings in the city, now once again serving as a mosque.

The most sensational discovery made during the archaeological study of the building is a fresco cycle of the life of St. Francis of Assisi in a small side chapel. This was executed during the Latin occupation of the city, probably about 1250, and is the earliest cycle of the life of St. Francis anywhere in the world, painted only about 25 years after his death. It shows the standing figure of the saint with ten scenes from his life and anticipates in many elements the frescoes of Giotto at Assisi. Other discoveries include a mosaic of the “Presentation of the Christ child in the Temple” dating probably to the seventh century, and thus the only pre-iconoclastic icon ever found in the city. Finally a late Byzantine mosaic of the Theotokos Kyriotissa came to light over the main door leading to the inner narthex, thus settling the much disputed dedication of the church. These paintings have been removed from the church and are now on exhibit in the Archaeological Museum, in the gallery devoted to Istanbul Through the Ages.

Excavations under and to the north of the church have revealed a whole series of earlier structures on the site. The earliest is the remains of a Roman bath of the late fourth or early fifth century, including a trilobed room, a circular chamber, and evidence of a hypocaust. This was succeeded by a basilica of the mid-sixth century built up against the Valens Aqueduct and utilizing the arches thereof as its north aisle. Finally, to the south of this, was built in the pre-iconoclastic period another church, part of the sanctuary and apse which were incorporated in the present building. Sections of the

opus sectile

floors of these earlier buildings were found under the floor of the existing apse.

Leaving the church we walk out to

Ş

ehzadeba

ş

ı

Caddesi and turn left. (The last section of the street on which we are walking is called Cüce Çe

ş

mesi Soka

ğ

ı

, the Street of the Dwarf’s Fountain.) A short distance along and on the right side of the street we see a small triangular medrese. This elegant little complex was built in 1606 by Kuyucu Murat Pa

ş

a, Grand Vezir in the reign of Ahmet I. Murat Pa

ş

a received his nickname

kuyucu

, or the pit-digger, from his favourite occupation of supervising the digging of trenches for the mass burials of the rebels he had slaughtered. The apex of the triangle is formed by the columned sebil, with simple classical lines. Facing the street is an arcade of shops in the middle of which a doorway leads to the courtyard of the medrese. Entering, we find the türbe of the founder in the acute angle behind the sebil, and at the other end the dershane, which, as so often, served also as a small mosque. This building has been taken over and restored by Istanbul University; the courtyard has been roofed in and used as a small museum, while the dershane contains a library.

Continuing along and passing the new University building, we turn right and soon come to another medrese complex, now the Istanbul University Institute of Turkology. This is a baroque building founded in 1745 by the Grand Vezir Seyyit Hasan Pa

ş

a, the same who built the han we saw earlier. It is curiously irregular in design and raised on a rather high platform so that on entering one mounts a flight of steps to the courtyard, now roofed in and used as a library and reading-room. In one corner is the dershane-mescit, which has become the office of the Director of the Institute; in another is a room designed as a primary school; this and the cells of the medrese are used for special library collections or as offices. Outside in the street at the corner of the buildings is a fine rococo sebil with a çe

ş

me beside it.

After leaving the medrese we continue walking along the same street, which soon veers left and ends in a flight of steps beside Beyazit’s hamam. We descend and find ourselves once more in the chaos of Beyazit Square, back at the point where we began our stroll.

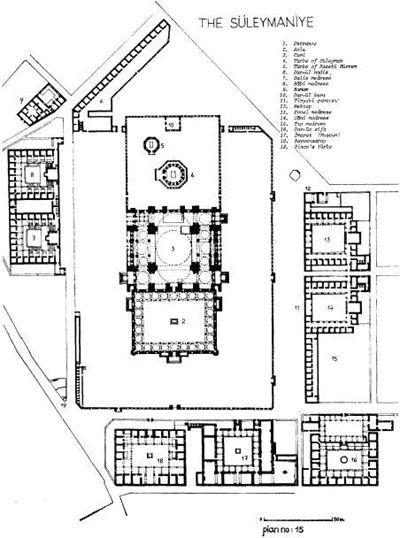

The Süleymaniye is the second largest but by far the finest and most magnificent of the imperial mosque complexes in the city. It is a fitting monument to its founder, Süleyman the Magnificent, and a masterwork of the greatest of Ottoman architects, the incomparable Sinan. The mosque itself, the largest of Sinan’s works, is perhaps inferior in perfection of design to that master’s Selimiye at Edirne, but it is incontestably the most important Ottoman building in Istanbul. For four and a half centuries it has attracted the wonder and enthusiasm of all travellers to the city.

The construction of the Süleymaniye began in 1550 and the mosque itself was completed in 1557, but it was some years later before all the buildings of the külliye were finished. The mosque stands in the centre of a vast outer courtyard surrounded on three sides by a wall with grilled windows. On the north side, where the land slopes sharply down towards the Golden Horn, the courtyard is supported by an elaborate vaulted substructure; from the terrace here one has a superb view of the Golden Horn, the hills of Pera on the other side, the Bosphorus, and the hills of Asia beyond. Around this courtyard on three sides are arranged the other buildings of the külliye with as much symmetry as the nature of the site would permit. Nearly all of these pious foundations have been well-restored and some of them are once again serving the people of Istanbul as they did in the days of Süleyman. We will later look at all of those which are presently open to the public, but first let us visit the great mosque itself.

THE MOSQUE

The mosque is preceded by the usual avlu, a porticoed courtyard of exceptional grandeur, with columns of the richest porphyry, marble and granite. The western portal of the court is flanked by a great pylon containing two stories of chambers; these, according to Evliya, were the muvakkithane, the house and workshop of the mosque astronomer. At the four corners of the courtyard rise the four great minarets. These four minarets are traditionally said to represent the fact that Süleyman was the fourth sultan to reign in Istanbul, while the ten

ş

erefes or balconies denote that he was the tenth sultan of the imperial line of Osman.

Entering the mosque we find ourselves in a vast almost square room surmounted by a dome. The interior is approximately 58.5 by 57.5 metres, while the diameter of the dome is 27.5 metres and the height of its crown above the floor is 47 metres. To east and west the dome is supported by semidomes, to north and south by arches with tympana filled with windows. The dome-arches rise from four great irregularly shaped piers. Up to this point the plan follows that of Haghia Sophia, but beyond this – as at the Beyazidive – all is different. Between the piers to north and south, triple arcades on two enormous monolithic columns support the tympana of the arches. There are no galleries here, nor can there properly be said to be aisles, since the great columns are so high and so far apart as not really to form a barrier between the central area and the walls; thus the immense space is not cut up into sections as at Haghia Sophia but is centralized and continuous. The method Sinan used to mask the huge buttresses required to support the four central piers is very ingenious: he has turned what is generally a liability in such a building into an asset, on three sides at least. On the north and south he incorporated the buttresses into the walls of the building, allowing them to project about equally within and without. He then proceeded to mask this projection on both sides by building galleries with arcades of columns between the buttresses. On the outside the gallery is double, with twice the number of columns in its upper storey as in its lower; on the inside there is a single gallery only. In both cases – especially on the outside – the device is extremely successful, and is indeed one of the things which gives the exterior its interesting and beautiful distinction. On the east and west façades the buttresses are smaller, for here the weight of the dome is distributed by the semidomes. On the eastern face, therefore, Sinan merely placed the buttresses wholly outside the building, where their moderate projection gives emphasis and variety to that façade. On the west, in our opinion, he was not so successful. Here, in order to preserve the unity of the courtyard and the grandeur of the western façade, he chose to place the buttresses wholly within the building. Again he masked them with galleries, but in this case the device was inadequate. The great west portal, instead of being impressive as it ought, seems squeezed tight by the deep projection of the buttresses, which moreover not only throw it into impenetrable shadow, but also abut in an unpleasing way on the two small domes on which the western semidome reposes. It can be said that Sinan rarely quite succeeded with the interior of his west walls; in almost every case, even in the smaller mosques, there is a tendency to squeeze the portal. But his solution of the main problem was masterly.