Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (29 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

We now find ourselves back on Uzun Çar

ş

ı

Caddesi, where we turn left and continue on downhill for a short distance. Just to the right of the next intersection rises Rüstem Pa

ş

a Camii, one of the most beautiful of the smaller mosques of Sinan. This mosque was built in 1561 by Rüstem Pa

ş

a, twice Grand Vezir under Süleyman the Magnificent and husband of the Sultans favourite daughter, the Princess Mihrimah. The rise of Rüstem Pa

ş

a began in the autumn of 1539, when he was engaged to marry Mihrimah. At that time he was governor of Diyarbak

ı

r, where his enemies tried to prevent him from marrying the princess by spreading the rumour that he had leprosy. But when the palace doctors examined Rüstem they found that he was infested with lice; consequently they declared that he was not leprous, for accepted medical belief was that lice never inhabit a leper. He was allowed to marry Mihrimah and Süleyman appointed him Second Vezir. Five years later he was made Grand Vezir, an office that he held from 1544 to 1553 and again from 1555 to 1561, during which time he became the wealthiest and most powerful of the Sultan’s subjects. Thus it was that Rüstem came to be called

Kehle-i-Ikbal

, the Louse of Fortune, from an old Turkish proverb that says: “When a man has his luck in place even a louse can bring him good fortune.”

The mosque is built on a high terrace over an interesting complex of vaulted shops, the rent from which went to maintain the foundation. Interior flights of steps lead up from the corners of the platform to a spacious and beautiful courtyard, unique in the city. The mosque is preceded by a curious double porch: first the usual type of porch consisting of five domed bays, and then, projecting from this, a deep and low-slung penthouse roof, its outer edge resting on a row of columns. This arrangement, although unusual, is very pleasant and has a definite architectural unity.

The plan of the mosque consists of an octagon inscribed in a rectangle: the dome rests on four semidomes, not in the axes but in the diagonals of the buildings; the arches of the dome spring from four octagonal pillars, two on the north, two on the south, and from piers projecting from the east and west walls. To north and south are galleries supported by the pillars and by small marble columns between them.

Rüstem Pa

ş

a Camii is especially famous for its very fine tiles which almost cover the walls, not only on the interior but also on the façade of the porch. One should also climb to the galleries where the tiles are of a different pattern. Like all the great Turkish tiles, those of Rüstem Pa

ş

a came from the kilns of Iznik in its greatest period (c. 1555–1620) and they show the tomato-red or “Armenian bole” which is characteristic of that period. These exquisite tiles, in every conceivable floral and geometric design, cover not only the walls, but also the columns, mihrab and mimber. Altogether they make one of the most beautiful and striking mosque interiors in the city.

Just to the east of Rüstem Pa

ş

a Camii, a few steps down Has

ı

rc

ı

lar Caddesi, we find a han whose origins may go back to early Byzantine times. This is the Hurmal

ı

Han, the Han for Dates; it has a long, narrow courtyard which one authority ascribes to the sixth or seventh century. There are a great many ancient hans in this neighbourhood, but they are for the most part decayed and cluttered, and almost nothing is known about them but their names.

BALKAPAN HAN

Continuing east along Has

ı

rc

ı

lar Caddesi for a few more steps we take the next right and then in the middle of the block turn left into a large courtyard. We are now in the Balkapan Han, the Honey-Store Han. Evliya Çelebi tells us that in his time this was the han of the Egyptian honey-merchants. The han is chiefly interesting for the extensive Byzantine vaults beneath it: these are reached by a staircase leading down from a shed in the middle of the courtyard. Great rectangular pillars of brick support massive brick vaulting in the usual herringbone pattern, covering an area of at least 2,000 square metres. This basement is used today, as it probably was originally, for storage of all kinds of goods. The vaults and superstructures on ground level were doubtless one of the many granaries or storage-depots which are known to have existed in this area from at least the fourth or fifth century.

Returning to Has

ı

rc

ı

lar Caddesi, we turn right and continue along until we come to the Spice Bazaar. Once inside we turn left and after passing through the Bazaar we find ourselves in the great square before Yeni Cami. Here, having completed our stroll through the principal markets and bazaars of Stamboul, we might be inclined to stop at the fish or vegetable markets of Eminönü and do a little shopping ourselves.

ı

t

and

Ş

ehzadeba

ş

ı

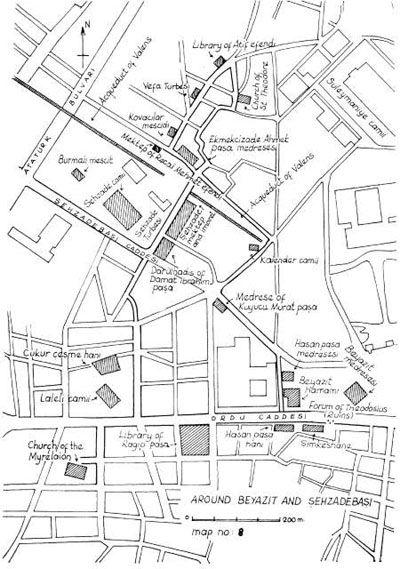

We will begin this stroll in Beyazit Square, which may fairly be said to be the centre of modern Stamboul. Indeed this square has been one of the focal points of the city for more than 15 centuries. In late Roman Constantinople this was known originally as the Forum Tauri, named after the colossal statue of a bull that once stood there. In 393 the square was rebuilt by the Emperor Theodosius I, the Great, and thenceforth it was called the Forum of Theodosius. The Forum of Theodosius was the largest of the public squares in Byzantine Constantine. It contained, among other things, a gigantic triumphal arch in the Roman fashion and a commemorative column with reliefs showing the triumphs of Theodosius, like that of Trajan in Rome. Colossal fragments of the triumphal arch and the commemorative column were found during reconstruction of Beyazit Square in the 1950s, and are now arrayed on both sides of Ordu Caddesi next to the two hans on one side and Beyazit’s hamam on the other. Notice the enormous Corinthian capitals and the columns curiously decorated with the lopped-branch design that we have seen on a column in the Basilica Cistern. Fragments of the commemorative column have also been revealed built into the foundations of the hamam, where they produce a startling effect. There we see the figures of marching Roman soldiers, some of them ingloriously standing on their heads!

At the very beginning of Ordu Caddesi, we see the remains of two enormous hans, each of which lost its front half when the avenue was widened in the 1950s. They were left in ruins, but both of them have since been restored and are once again functioning as commercial buildings. The one to the east is

Ş

imke

ş

hane, and was originally built as a mint by Mehmet the Conqueror. The mint was later transferred to Topkap

ı

Saray

ı

and

Ş

imke

ş

hane was used to house the spinners of silver thread. The han was damaged by fire and then rebuilt in 1707 by Râbia Gülnü

ş

Ümmetullah, wife of Mehmet IV and mother of Mustafa II and Ahmet III. The han to the west was built about 1740 by the Grand Vezir Seyyit Hasan Pa

ş

a. Both were handsome and interesting buildings, especially the latter. It is still worthwhile walking round them to see the astonishing and picturesque irregularity of design: great zigzags built out on corbels following the crooked line of the streets.

Some few hundred metres farther on down Ordu Caddesi, and on the same side of the street, we come to the külliye of Rag

ı

p Pa

ş

a. This delightful little complex was founded in 1762 by Rag

ı

p Pa

ş

a, Grand Vezir in the reign of Mustafa III. The architect seems to have been Mehmet Tahir A

ğ

a, whose masterpiece, Laleli Camii, is a little farther down Ordu Caddesi and on the opposite side of the avenue. We enter through a gate on top of which is a mektep, or primary school, now used as a children’s library. Across the courtyard, surrounded by an attractive garden, is the main library; this has been restored in recent years and is now once again serving its original purpose. From the courtyard a flight of steps leads to a domed lobby which opens into the reading-room. This is square, the central space being covered by a dome supported on four columns; between these, beautiful bronze grilles form a kind of cage in which are kept the books and manuscripts. Round the sides of this vaulted and domed room are chairs and tables for reading. The walls are revetted in blue and white tiles, either of European manufacture or strongly under European influence, but charming nevertheless. In the garden, which is separated from the courtyard by fine bronze grilles, is the pretty open türbe of the founder. Rag

ı

p Pa

ş

a, who was Grand Vezir from 1757 until 1763, is considered to have been the last of the great men to hold that office, comparable in stature to men like Sokollu Mehmet Pa

ş

a and the Köprülüs. Rag

ı

p Pa

ş

a was also the best poet of his time and composed some of the most apt and witty of the chronograms inscribed on the street-fountains of Istanbul. His little külliye, though clearly baroque in detail, has a classic simplicity which recalls that of the Köprülü complex on the Second Hill.

BODRUM CAM

İİ

(CHURCH OF THE MYRELAION)

We now continue along Ordu Caddesi and take the second turning on the left, just opposite Laleli Camii. We then turn right at the next corner and at the end of this street ascend a flight of steps onto a large marble-paved terrace. Just beyond the far left corner of the terrace we see a former Byzantine church known locally as Bodrum Camii, or the Basement Mosque, because of the crypt that lies beneath it. The building was excavated in 1964–6 by Professor Cecil L. Striker of the University of Pennsylvania, who identified the church as the Myrelaion, “the place of the sacred myrrh”, built by the Emperor Romanus I Lecapenus (r. 919–44) at the beginning of his reign along with a monastery of the same name. Beneath the church he built a funerary chapel, where he interred his wife Theodora after she died in 922. Next to the church and monastery Romanus also erected a palace on the substructure of an earlier Roman edifice, known as the Rotunda, beneath the marble terrace we see today. The church was converted into a mosque late in the fifteenth century by Mesih Pasha, a descendant of the Palaeologues who converted to Islam and led the forces of Mehmet II in their first and unsuccessful attack on Rhodes in 1480. The building was several times gutted by fire and was restored in 1965–6, along with the chapel beneath it, and it is once again serving as a mosque, while the Rotunda has been rebuilt as a subterranean shopping mall, with its entrance on the south side of the terrace opposite the mosque.