Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (25 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

Almost opposite the north minaret stands the extremely impressive imaret of the külliye. The imaret, in addition to serving as a public kitchen, seems also to have been used as a kervansaray. The various rooms of the imaret line three sides of the courtyard (now roofed in), with the fourth side containing the monumental entrance-portal. The first room on the right housed an olive-press, the second was a grain storeroom, and the third, in the right-hand corner, was the bakery, equipped with two huge ovens. The large domed chamber at the far end of the courtyard was the kitchen and dining room. The even larger domed structure beside it, forming the left third of the complex, served as a stable for the horses and camels of the travellers who were guests at the imaret, while the chamber between the stable and the courtyard was used as a dormitory. The imaret was converted into a library by Sultan Abdül Hamit II in 1882; it now houses the State Library (Devlet Kütüphanesi). The library is an important one of 120,000 volumes and more than 7,000 manuscripts and the imaret makes a fine home for it.

The medrese of Beyazit’s külliye is at the far west end of the square. It is of the standard form; the hücres, or cells, where the students lived and studied, are ranged around four sides of a porticoed courtyard, while the dershane, or lecture-hall, is opposite the entrance portal. This building has also been converted into a library, that of the Municipality (Belediye Kütüphanesi); unfortunately the restoration and conversion were rather badly done, a lot of cement having been used instead of stone and the portico having been very crudely glassed in. Nevertheless, the proportions of the building are so good and the garden in the courtyard so attractive that the general effect is still quite charming.

The medrese is now used to house the Museum of Calligraphic Art. The collections of the museum are organized into various sections; these are: Cufic Kurans, treatises and manuscripts and panels in Indian and Moroccan scripts; Nakshi Kurans and wooden cut-outs; Ta’liq Kurans and Tuluth panels; Ta’liq manuscripts and panels; Tuluth Nakshi collages and calligraphic compositions; the Holy Relics and dar-ül kürsa; Tuluth and mirror writings; Ta’liq panels, compositions, Tuluth and Nakshi Kurans; tu

ğ

ras and Nakshi Kurans; Hilyes (descriptions of the features and qualities of the Prophet); embroidered inscriptions and works by women calligraphers; calligraphic models and Muhakkak Kurans. There are also examples of calligraphic inscriptions on wood, stone and glass, and other examples of the use of calligraphy, including title deeds, family trees, and even a talismanic shirt. There are also interesting exhibits of calligraphic equipment, and one cell has been set up with wax models showing a calligrapher instructing his students in this quintessentially Islamic art form, wonderfully evoked in this interesting museum.

Beyond the medrese, facing on the wide Ordu Caddesi that leads down into the valley at Aksaray, are the splendid ruins of Beyazit’s hamam. This must have been among the most magnificent in the city, and it is now being restored from near ruin; the fabric still seems to be essentially in good condition. It is a double hamam, the two sections being almost identical, the women’s a little smaller than the men’s. Apart from the monumental façade housing the two camekâns with their great domes, the best view of the hamam may be had from the second floor of the University building just beyond; from here one sees the elaborate series of domes and vaults that cover the so

ğ

ukluk and the hararet.

ISTANBUL UNIVERSITY AND THE BEYAZIT TOWER

On the north side of Beyazit Square stand the main buildings of the University of Istanbul. Immediately after the Conquest Sultan Mehmet II founded a medrese at the Aya Sofya mosque and a few years later he built the eight great medreses which were attached to his mosque; other such institutions were added by Beyaz

ı

t II, Selim I, and above all by Süleyman, who surrounded his own mosque with another seven medreses. In addition to Theology and Philosophy, there were Faculties of Law, Medicine and Science. But the decline of the Empire was accompanied by a corresponding decline of learning. The first attempt to establish a secular institution of higher learning, known in Turkish as Darülfunun, was begun during the reign of Sultan Abdül Mecit I (r. 1839–61), as part of the reform movement known as the Tanzimat. The Darülfunun, which registered its first students in 1869, was reorganized in 1900 on the model of European universities, including faculties of science, medicine and civil law. After the founding of the Republic of Turkey in 1923 the Darülfunun was reformed and reorganized to become the University of Istanbul. It was then installed in its present building, previously the Seraskerat, or Ministry of War. The main part of the building was constructed by the French architect Bourgeois in 1866 in the sumptuous stylelessness then thought appropriate to ministerial edifices; and during the last two decades or so various wings have been added, equally styleless but not nearly so sumptuous.

The area on which these central buildings of the University stand formed part of the site where Mehmet the Conqueror built the Eski Saray, or Old Seraglio, immediately after the Conquest. Somewhat later he began to build Topkap

ı

Saray

ı

on the First Hill and the Eski Saray was gradually abandoned as the official residence of the sultans. Some of its various and extensive buildings were used as a place of claustration for the women of defunct sultans, others as private palaces of distinguished vezirs; and a large part of its grounds was appropriated by Süleyman for his great mosque complex. In the end the whole thing disappeared and has left not a trace behind.

In the courtyard of the university stands the Beyazit Tower, a characteristic feature of the Stamboul skyline. There had long been a wooden tower at this point for fire-watchers, but it was not until 1828 that Mahmut II caused the tower to be built. It is some 50 metres high, and its upper platform commands a view of the entire city if one can obtain permission to enter.

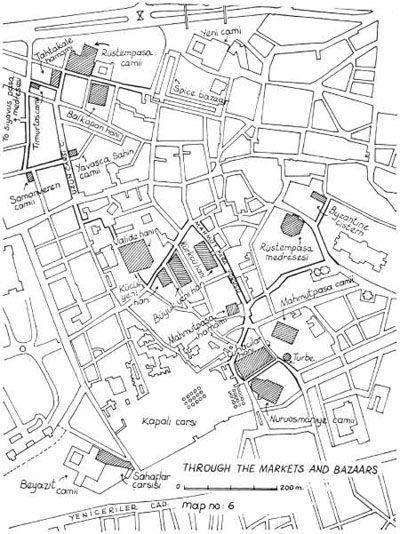

Markets and Bazaars

The region between Beyazit Square and the Galata Bridge is the principal market district of the city. This is one of the oldest and most picturesque quarters of Stamboul, and the tumultuous streets are full of clamour and commotion, with cars, trucks, carts and porters forcing their way through the milling crowds of shoppers and pavement vendors. Although colourful and fascinating, this neighbourhood can be somewhat wearing for the stroller, for it is often difficult to find one’s way in the narrow, winding streets, most of which are not identified by signs, and one is continually fleeing to avoid being knocked down by herculean porters or run down by a lorry. And so, before beginning this tour, one is advised to prepare oneself, as do the Stamboullus, by having a bracing glass of tea in Ç

ı

naralt

ı

, the old outdoor çayevi in Beyazit Square.

While sitting in the teahouse one can observe some of the streetside shops and markets which are so characteristic of this district. The street at the far end of the square is called Bak

ı

rc

ı

lar Caddesi, the Avenue of the Copper-Workers, where most of the coppersmiths of the city make and sell their wares. We will find that many of the streets in this district are named after the tradesmen and artisans who carry on their activies there, as they have for centuries past.

Leaving the teahouse, we pass through the gate beside the mosque (the Gate of the Spoon-Makers) and enter the Sahaflar Çar

ş

ı

s

ı

, the Market of the Secondhand Book Sellers. The Sahaflar Çar

ş

ı

s

ı

is one of the most ancient markets in the city, occupying the site of the Chartoprateia, the book and paper market of Byzantium. After the Conquest this became the market for the turban-makers and metal-engravers, at which time it was called the Hakkaklar Çar

ş

ı

s

ı

, named after the latter of those two guilds. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, during the reign of Sultan Ahmet III, the booksellers set up shop here too, moving from their old quarters inside the Covered Bazaar. In the second half of the eighteenth century, with the legalization of printing in the Ottoman Empire, the booksellers greatly increased their trade and came to dominate the market, which from that time on came to be named after them. During the nineteenth and early twentieth century, the Sahaflar Çar

ş

ı

s

ı

was one of the principal centres in the Ottoman Empire for the sale and distribution of books. In the past half-century, however, the establishment of public libraries and modern bookshops has diminished its importance and it now lives on in honourable old age as a market for secondhand books. It is one of the most picturesque spots in Stamboul; a pleasant, vine-covered, sun-dappled courtyard lined with tome-crammed shops, with stalls and barrows outside piled high with a veritable literary necropolis. The guild of the booksellers in this market is one of the oldest in Istanbul; its origins, like those of many other guilds in the city, go back to the days of Byzantium. In the centre of the square there is a modern bust of Ibrahim Müteferrika, who in 1732 began to print the first works in Turkish.

We pass through the Sahaflar Çar

ş

ı

s

ı

and leave at the other end through an ancient stone portal, Hakkaklar Kap

ı

s

ı

, the Gate of the Engrayers. We then turn right, and a few steps farther on we find on our left one of the entrances to the famous Kapal

ı

Çar

ş

ı

, the Covered Bazaar.

Most foreigners, and indeed most Stamboullus, find the Covered Bazaar one of the most fascinating and irresistible attractions of Istanbul. No directions need be given for a stroll through the Bazaar, for it is a labyrinth in which one takes delight in getting lost and finding one’s way out, after who knows how many purchases and other adventures. As can be seen from the plan, it is a fairly regular structure – which makes it even more maze-like and confusing in practice. It is a small city in itself: according to a survey made in 1880 the Bazaar contained at that time 4,399 shops, 2,195 ateliers, 497 stalls, 12 storehouses, 18 fountains, 12 mescits or small mosques, as well as a larger mosque, a primary school and a türbe. The number of commercial establishments would appear to be about the same now, in addition to which there have been added several new institutions, including half a dozen restaurants (the best is the Havuzlu Lokanta), innumerable teahouses, two banks, plus a toilet and information centre for lost tourists.