Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (22 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

What one sees inside the museum is the north-east portico of the Peristyle. There has been considerable disagreement about the date of these mosaics. The arguments are far too technical and complex to be entered into here, but the upshot is that late Roman mosaics of this sort – they belong to the same general type as those at Antioch, at Apamea, at Piazza Armerina in Sicily, in North Africa and elsewhere – cannot be exactly dated on stylistic grounds alone. But current opinion is that the mosaics date from the reign of Justinian (r. 527–65), probably when he restored the Great Palace after the Nika Revolt in 532.

We leave by the upper gate of the museum, where we turn right on Kabasakal Soka

ğ

i, the Street of the Bushy Beard. This is a picturesque seventeenth-century Ottoman arasta, or market street, which was part of the külliye of Sultan Ahmet Camii. The arasta was restored from utter ruin in the 1980s and is now once again serving as a market street, principally for the tourist trade.

At the end of the arasta we turn left on Mimar Mehmet A

ğ

a Caddesi, where we turn left and walk back towards the garden between the Blue Mosque and Haghia Sophia. Here we turn right onto Kabasakal Soka

ğ

ı

, the continuation of the old bazaar street. This passes on its left the Hamam of Roxelana and on its right the seventeenth-century medrese of Cedid Mehmet Efendi and a nineteenth-century mansion known as Ye

ş

il Ev, the Green House. Both of the latter buildings were restored in the 1980s by the Turkish Touring and Automobile Club. The cells of the medrese now house shops where artisans specializing in old Ottoman crafts make and sell their works. Ye

ş

il Ev is now an elegant hotel with an excellent restaurant, which in the summer months spreads out into the very pleasant rear courtyard, a perfect place to restore oneself after a long stroll around the First Hill.

Haghia Sophia

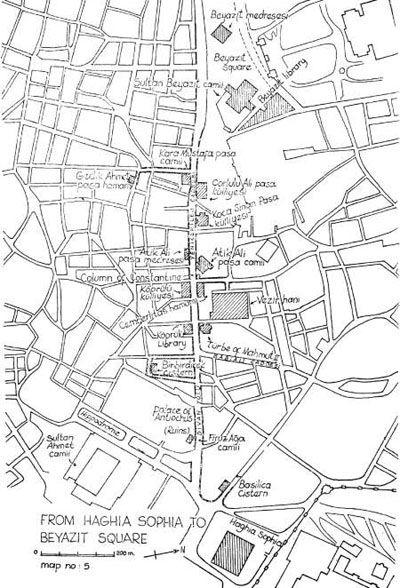

to Beyazit Square

Aya Sofya Meydan

ı

, the square beside Haghia Sophia, occupies a site which was once the heart of Byzantine Constantinople. The square coincides almost exactly with the Augustaeum, the publc forecourt to the Great Palace of Byzantium. On its northern side the Augustaeum gave access to the church of Haghia Sophia and to the Patriarchal Palace, while outside its south-eastern corner stood the Chalke, or Brazen House, the monumental vestibule of the Great Palace. The Hippodrome was located just to the south-west of the Augustaeum and the Baths of Zeuxippus were to its south. A short way to the west of the Augustaeum there was another great communal square, the Stoa Basilica, a porticoed piazza surrounded by the buildings of the University of Constantinople, the central law courts of the empire, the principal public library, and a large outdoor book market. Thus the Augustaeum and its immediate neighbourhood were at the very hub of life in the ancient city. Today the square is no longer a civic centre, but it is still a very central starting point for visting the antiquities on the First and Second Hills of the old city.

At the south-western corner of the Augustaeum, at the beginning of the modern Divan Yolu, there stood a monument called the Miliarum Aureum, the Golden Milestone, known more simply as the Milion. Excavations in 1965 unearthed a fragment of the Milion beside the Ottoman suterazi, or water-control tower, just to the right at the beginning of Divan Yolu. The fragment, a tall marble stele, was part of a four-sided ceremonial archway surmounted by statues of Constantine the Great and his mother Helena, holding between them the True Cross.

The Milion, like its namesake in the Roman Forum, was the point of departure for the great roads which ran out of the city and was the reference point for their milestones. Here began the Mese, or Middle Way, the main thoroughfare of ancient Constantinople, which followed the course of the modern Divan Yolu. The Mese, which was flanked for a good part of its length with marble porticoes, led westward from the Milion along the ridge between the First and Second Hills, atop which it passed through the Forum of Constantine. Continuing westward, along the route of the Modern Yeniçeriler Caddesi, the Avenue of the Janissaries, the Mese then ran along the ridge between the Second and Third Hills and entered the Forum of Theodosius, on the site of the present-day Beyazit Square. Beyond there, the Mese divided into two branches, one of which extended west and the other south-west. The western branch passed through the Gate of Charisius, where it joined the Roman road to Adrianople, now known as Edirne. The other branch passed through the famous Golden Gate and linked up with the Via Egnatia, which marched through Thrace, Macedonia and Epirus to the Adriatic. The main thoroughfares of modern Stamboul follow quite closely the course of these Roman roads built more than 15 centuries ago.

The thoroughfare between Haghia Sophia and Beyazit Square continued to be one of the principal arteries of the town in Ottoman times, for it was the main road from Topkap

ı

Saray

ı

to the centre of Stamboul. For that reason it is lined with monuments of the imperial Ottoman centuries, as well as some ruined remnants of imperial Byzantium. It is called Divan Yolu, the Road of the Divan, because of the procession of dignitaries that passed along it whenever there were meetings of the Divan, or imperial council, in the Second Court of Topkap

ı

Saray

ı

.

THE BAS

İ

L

İ

CA CISTERN

The first monument on our itinerary is a short way down Yerebatan Caddesi, the street that leads off half-right from Aya Sofya Meydan

ı

at the beginning of Divan Yolu. Almost immediately on the left we come to a small building which is the entrance to an enormous underground cistern, Yerebatan Saray, or the Underground Palace. Restoration of the cistern began in 1985 and it opened to the public in 1988.

The structure was known in Byzantium as the Basilica Cistern because it lay underneath the Stoa Basilica, the second of the two great squares on the First Hill. The Basilica Cistern was built by Justinian after the Nika Revolt in 532, possibly as an enlargement of an earlier cistern of Constantine. Throughout the Byzantine period the Basilica Cistern was used to store water for the Great Palace and the other buildings on the First Hill, and after the Conquest its waters were used for the gardens of Topkap

ı

Saray

ı

. Nevertheless, general knowledge of the cistern’s existence seems to have been lost in the century after the Conquest, and it was not rediscovered until 1546. In that year Petrus Gyllius, while engaged in his study of the surviving Byzantine antiquities in the city, learned that the people in this neighbourhood obtained water by lowering buckets through holes in their basement floors; some even caught fish from there. Gyllius made a thorough search through the neighbourhood and finally found a house through whose basement he could go down into the cistern, probably at the spot where the modern entrance is located. As Gyllius writes, referring to the Stoa Balica as the Imperial Portico:

The Imperial Portico is not to be seen, though the Cistern remains. Through the inhabitants’ carelessness and contempt for everything that is curious it was never discovered except by me, who was a stranger among them, after a long and diligent search for it. The whole area was built over, which made it less suspected that there was a cistern there. The people had not the least suspicion of it, though they daily drew their water out of the wells that were sunk into it. By chance I went into a house where there was a way down to it and went aboard a little skiff. I discovered it after the master of the house lit some torches and rowed me here and there through the pillars, which lay very deep in water. He was very intent on catching his fish, with which the Cistern abounds, and speared some of them by the light of the torches. There is also a small light that descends from the mouth of the well and reflects on the water, where the fish usually come for air.

The Cistern is three hundred and thirty-six feet long, a hundred and eighty two feet broad, and two hundred and twenty-four Roman paces in circumference. The roof, arches and sides are all brickwork covered with terra-cotta, which is not the least impaired by time. The roof is supported by three hundred and thirty six pillars. The space of the intercolumniation is twelve feet. Each pillar is over forty feet, nine inches high. They stand lengthwise in twelve ranges, broadways in twenty-eight… There is an abundance of wells that empty into the Cistern. When it was filling in the winter time I saw a large stream of water filling from a great pipe with mighty noise until the pillars were covered up with water to the middle of the capitals. This Cistern stands west of the Church of St. Sophia a distance of eighty Roman paces.

Ninety of the columns in the south-west corner were walled off in the nineteenth century. The columns are topped by Byzantine Corinthian capitals; these have imposts above them which support little domes of brick in a herringbone pattern. One of the columns on the left side is carved with a curious peacock-eye or lopped branch design. This identifies it as part of the triumphal arch in the Forum of Theodosius I on the Third Hill (see Chapter 9), where fragments of identical columns were excavated in 1965. In the far left corner of the cistern, at a slightly lower level, one of the columns is mounted on ancient classical bases supported by the heads of Gorgons, one of them upside down and the other on its side. (The Gorgons in Greek mythology were three sisters, one of whom, Medusa, was slain by Perseus.) These Gorgon heads and the two we have seen outside the Archaeological Museum were, as we have noted, originally in the Forum of Constantine, whose site we will see later on this itinerary.

FIRUZ A

Ğ

A CAM

İİ

On leaving Yerebatan Saray, we retrace our steps and return once again to the beginning of Divan Yolu; 100 metres or so up Divan Yolu and on its left side, we see a tiny mosque, one of the oldest in the city. It was constructed in 1491 for Firuz A

ğ

a, Chief Treasurer in the reign of Sultan Beyazit II. Firuz A

ğ

a Camii is of interest principally because it is one of the few examples in Istanbul of a mosque of the “pre-classical” period, that is, of those built before 1500. This is the architectural style which flourished principally in the city of Bursa when it was the capital of the Ottoman Empire, before the Conquest. In form, Firuz A

ğ

a Camii is quite simple, consisting merely of a square room covered by a windowless dome resting on the walls, the so-called single unit type of mosque. The building is preceded by a little porch of three bays, typical of the single-unit Bursa mosques, while the minaret, unusually, is on the left-hand side. The tomb of the founder, in the form of a marble sarcophagus, is on the terrace beside the mosque. Firuz A

ğ

a Camii is an elegant little building, perhaps the most handsome of the early mosques of its type in the city.

THE PALACES OF ANT

İ

OCHUS AND LAUSUS

Just beyond Firuz A

ğ

a Camii, there is a little park which borders an open area excavated some years ago. The ruins which were exposed in these excavations are so fragmentary that it is difficult to determine their identity. It is thought that what we see here are the ruins of two adjacent palaces, those of Antiochus and Lausus, two noblemen of the early fifth century. The grandest of these is the palace of Antiochus, an hexagonal building with five deep semicircular apses with circular rooms between the apses. In the early seventh century, this palace was converted into a martyrium for the body of St. Euphemia when it was taken from Chalcedon to Constantinople. This lady was a virgin, martyred in Chalcedon in about the year 303. We learn from the Anonymous Englishman, writing in 1190, that St. Euphemia performed an astonishing miracle during the Oecumenical Council at Chalcedon in 451. According to his account, the two opposing parties in the Council, the Orthodox and the Monophysites, decided to resolve their dispute about the nature of Christ by placing their formulas in the saint’s casket and letting her decide. A week later they opened the casket and found the Orthodox formula upon her heart and that of the Monophysites lying under her feet, thus bringing victory to the Orthodox party. The martyrium is elaborately decorated with paintings in fresco, representing scenes from the life and especially the gaudy martyrdom of St. Euphemia, and a striking picture of the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste; these are preserved in rather bad condition under a shed beside the Law Courts. They were at first ascribed to the ninth century but the latest study places them in the late thirteenth. Unfortunately, the shed covering the frescoes is closed permanently and the paintings can no longer be seen by the public.