Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (26 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

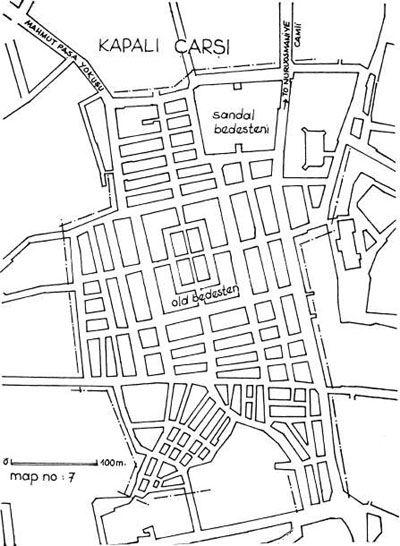

The Bazaar was established on its present site and covering almost the same area by Sultan Mehmet II, a few years after the Conquest. Although it has been destroyed several times by fire, the most recent in 1954, the Bazaar is essentially the same in structure and appearance as it was when it was built four centuries ago. The street-names in the Bazaar come from the various guilds that have worked or traded in those same locations now for centuries. Some of these names, such as the Street of the Turban-Makers and the Street of the A

ğ

a’s Plumes, commemorate long-vanished trades and remind us that much of the fabled Oriental atmosphere of the Bazaar has vanished in recent decades. A century ago the Bazaar was more quaint and picturesque, and stocked with more unusual and distinctive wares than it is today. But even now, in spite of the intrusion of modern shoddy and mass-made goods, there is still much to be found that is ancient and local and genuine. Shops selling the same kind of things tend to be congregated together in their own streets: thus there is a fine colonnaded street of oriental rug-merchants, whose wares range all the way from magnificent museum-pieces to cheap modern imitations. Here too are sold brocades and damasks, antique costumes, and the little embroidered towels so typically Turkish. There are streets of jewellers, goldsmiths and silversmiths, of furniture-dealers, haberdashers, shoemakers and ironmongers. In short, every taste is catered to; one has but to wander and inspect and bargain. Bargaining is most important; nobody expects to receive the price first asked, and part of the fun consists in making a good bargain. Almost all of the dealers speak half a dozen languages, and there is little difficulty in communication. But time is essential: a good bargain can rarely be struck in a few moments – often it requires a leisurely cup of Turkish coffee, freely supplied by the dealer.

In the centre of the Bazaar is the great domed hall known as the Old Bedesten. This is one of the original structures surviving from Fatih’s time. Then, as now, it was used to house the most precious wares, for it can be securely locked and guarded at night. Some of the most interesting and valuable objects in the Bazaar are sold here: brass and copper of every description, often old and fine; ancient swords and weapons, antique jewellery and costumes, fine glassware, antique coins, and classical and Byzantine pottery and figurines. As we might expect, not all of the antiquities sold in the Bedesten are authentic. Nevertheless, many of the imitations are of excellent workmanship, for the craftsmen who made them often belong to the same guild as those who did the originals, using the same tools and techniques as their predecessors.

If we leave the Bedesten through the Gate of the Goldsmiths we will notice above the outer portal the figure, in low relief, of a single-headed Byzantine eagle. This was the imperial emblem of the Comneni dynasty, which ruled over Byzantium in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. This has suggested to some that the Old Bedesten was originally of Byzantine construction, although most scholars are agreed that it was built in Fatih’s time. In his

Seyahatname

, Evliya Çelebi describes this eagle and gives us his own original view of its significance: “Above the Gate of the Goldsmiths there is represented a formidable bird opening its wings. The meaning of the symbol is this: ‘Gain and trade are like a wild bird, which if it is to be domesticated by courtesy and politeness, may be done so in the Beclesten’.”

The Gate of the Goldsmiths opens onto Inciciler Soka

ğ

ı

, the Street of the Pearl-Merchants. If we follow this street and take the third turning on the right, we will soon come to one of the gateways of the Sandal Bedesteni. This is often called the New Bedesten because it was built some time after Fatih’s Bedesten, perhaps early in the sixteenth century, when the great increase in trade and commerce required an additional market and storehouse for valuables. The Sandal Bedesteni is far less colourful in its activities than the Old Bedesten, for it is almost empty most of the time. But for that reason we can examine its splendid structure more easily, with its 12 massive piers, in four rows of three each, supporting 20 brick domes. The best time to visit the Sandal Bedesteni is on Monday and Thursday at one o’clock in the afternoon, when the rug auctions are held. These auctions take place in what looks like a little odeum in the centre of the Bedesten, where rug merchants and spectators, many of them canny Anatolians, sit and bid upon the rugs, carpets and kilims which the sellers exhibit on the floor. At those times one can recapture something of the old Oriental atmosphere of the Covered Bazaar.

We leave the Kapal

ı

Çar

ş

ı

by the door at the far end of the Bedesten. Turning right on the street outside, we see on our left an arcade of finely built shops which forms the outer courtyard wall of Nuruosmaniye Camii. These shops were originally part of the Nuruosmaniye külliyesi and their revenues were used to help pay for the upkeep of the mosque and its dependencies. These shops have recently been restored in an attractive manner and are now once again performing their original function.

NURUOSMAN

İ

YE CAM

İİ

At the end of the arcade of shops we come on our left to the gate of the courtyard of Nuruosmaniye Camii, just opposite Çar

ş

ı

Kap

ı

, one of the main entryways to the Kapal

ı

Çar

ş

ı

. This is one of the most attractive mosque courtyards in the city, shaded by plane-trees and horse-chestnuts, with the mosque on the left and the various buildings of the külliye – the medrese, library, türbe and sebil – scattered here and there irregularly. The courtyard is a busy one, situated as it is beside one of the main gates of the Bazaar, and is much frequented by beggars and peddlers. Now and then one sees here one of the itinerant folk-musicians called

a

ş

ı

klar

, who recite and sing their own poetry and songs while playing upon the

saz.

The

a

ş

ı

klar

follow a tradition which is many centuries old, and are among the last survivors of the wandering bards and minstrels of the medieval world. Their songs and poems are concerned with all aspects of Turkish life, including politics, which is why they are so often in trouble with the police. But in the end the

a

ş

ı

klar

(their name literally means ‘Lover’) always sing to their peasant audiences ballads of life and love in Anatolia, and so their songs are generally sad.

Nuruosmaniye Camii was begun by Sultan Mahmut I in 1748 and finished in 1755 by his brother and successor, Osman III, from whom it takes its name, the mosque of the Sacred Light (Nur) of Osman. It was the first large and ambitious Ottoman building to exemplify the new baroque style introduced from Europe. Like most of the baroque mosques, it consists essentially of a square room covered by a large dome resting on four arches in the walls; the form of these arches is strongly emphasized, especially on the exterior. In plan, the present building has an oddly cruciform appearance because of the two side-chambers at the east end, and it has a semicircular apse for the mihrab. On the west it is preceded by a porch with nine bays, and this is enclosed by an extremely curious courtyard which can only be described as a semicircle with seven sides and nine domed bays! At the north-east corner of the mosque an oddly-shaped ramp, supported on wide arches, leads to the sultans loge. (Note that a large number of the arches here and elsewhere in the building are semicircular instead of pointed in form, as they are generally in earlier mosques.) The whole structure is erected on a low terrace to which irregularly placed flights of steps give access.

Nuruosmaniye Camii is altogether an astonishing building, not wholly without a certain perverse genius. But its proportions are awkward and ungainly and its oddly-shaped members seem to have no organic unity but to be the result of an arbitrary whim of the architect. (He seems to have been a Greek by the name of Simeon.) Also the stone from which it is built is harsh and steel-like in texture and dull in colour. All things considered, the mosque must be pronounced a failure, but a charming one.

Leaving the mosque courtyard by the gate at the far end, we turn left on the street outside. A little way along, just past the first turning on the left, we veer right into a picturesque little square, one side of which is lined with old wooden houses. This is the outer courtyard of Mahmut Pa

ş

a Camii, one of the very oldest mosques in the city. Mahmut Pa

ş

a Camii is interesting not only because of its great age, but because it is a very fine example of the typical Bursa style of mosque structure. Built in 1462, only nine years after the Conquest, it was founded by Fatih’s famous Grand Vezir, Mahmut Pa

ş

a. This distinguished man was of Byzantine origin: his paternal grandfather, Philaninos, had been ruler of Greece with the rank and title of Caesar. Mahmut Pa

ş

a’s contemporary, the historian Kritovoulos, gives this attractive picture of him: “This man had so fine a nature that he outshone not only all his contemporaries but also his predecessors in wisdom, bravery, virtue and other good qualities... He was enterprising, a good counselor, bold, courageous, excelling in all lines, as the times and circumstances proved him to be. For from the time he took charge of the affairs of the great Sultan, he gave everything in this great dominion a better prospect by his wonderful zeal and his fine planning as well as by his implicit faith in and good-will toward his sovereign.” He was in addition a great patron of learning and the arts, especially poetry. He was put to death by the Conqueror in 1474.

The general plan of the mosque resembles fairly closely that of Sultan Murat I at Bursa. Essentially it consists of a long rectangular room divided in the middle by an arch, thus forming two square chambers each covered by a dome of equal size. On each side of the main hall runs a narrow, barrel-vaulted passage which communicates both with the hall and with three small rooms on each side. To the west a narthex or vestibule with five bays runs the width of the building and is preceded by a porch with five bays.

Let us look at some of the details. The porch is an unfortunate restoration, in which the original columns have been replaced by, or encased in, ungainly octagonal piers. Over and beside the entrance portal are several inscriptions in Arabic and Osmanl

ı

(Old Turkish) verse giving the dates of foundation and of two restorations, one in A.H. 1169 (A.D. 1755) and another in A.H. 1244 (A.D. 1828). The ugly piers are undoubtedly due to this last restoration, since they are characteristically baroque. The entrance portal itself clearly belongs to the same period. On entering one finds oneself in the narthex – a most unusual feature for a mosque, found only once or twice at Bursa and at the Beyazidiye here. The vaults of the narthex are interesting and different from one another. The central bay has a square vault heavily adorned with stalactites. In the first two bays on either side smooth pendentives support domes with 24 ribs; while in the two end ones the domes are not supported by pendentives at all, but by a very curious arrangement of juxtaposed triangles so that the dome rests on a regular 16-sided polygon. Other examples of this odd and not unattractive expedient are found in the west dome of Murat Pa

ş

a Camii (see Chapter 16) and in one or two other mosques which belong to the same early period.