Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (54 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

Before we leave St. John’s, we might read what one of the monks of the Studion wrote in praise of it some centuries ago, apparently in a moment of great happiness: “No barbarian looks upon my face, no woman hears my voice. For a thousand years no useless man has entered the monastery of the Studion, none of the female sex has trodden its court. I dwell in a cell that is like a palace; a garden, an olive grove and a vineyard surround me. Before me there are graceful and luxuriant cypress trees. On one hand is the great city with its market places and on the other the mother of churches and the empire of the world.”

Leaving the church we turn left and follow the winding path which leads us around to the south-eastern corner of its outer precincts. Here, at the edge of a vacant field, we find a small shed which gives access to a covered cistern which was once part of the Studion. It is quite impressive, containing 23 granite columns with handsome Corinthian capitals. Beside it is an ayazma, or holy well, with two columns.

After leaving the cistern we continue on in the same direction until we arrive at the railway line. There we turn left and follow the railway as far as the first underpass, from which a path leads us out to the sea-walls. There we turn right and in a few steps come to a portal called Narl

ı

Kap

ı

, the ancient Pomegranate Gate, whence a path takes us out to the Marmara road. Here we can stroll back towards town along the shore, enjoying a splendid view of the Stamboul skyline.

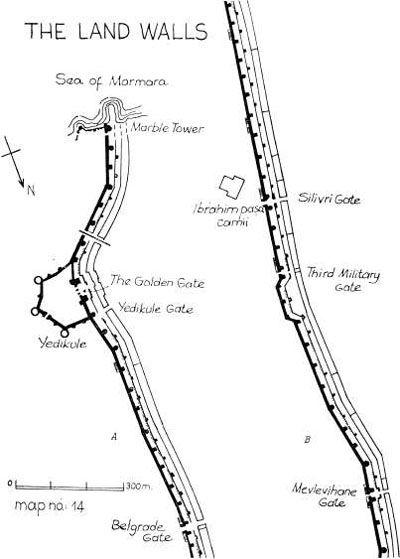

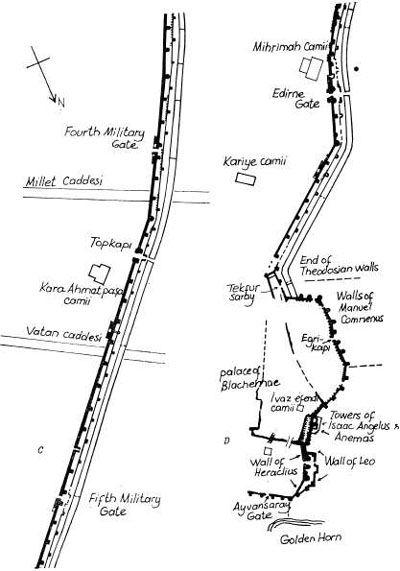

the Land Walls

The Byzantine land-walls extend from the Sea of Marmara to the Golden Horn, a total distance of about 6.5 kilometres. These walls protected Byzantium from its enemies for more than 1,000 years, and in that way profoundly influenced the history of medieval Europe. Although they are now in ruins, the walls of Byzantium are still a splendid and impressive sight, with towers and battlements marching across the hills and valleys of Thrace. Although a hike along the land-walls can be somewhat arduous, it is nevertheless quite rewarding, for on and around them we discover aspects of Stamboul which are not evident within the town itself. And in springtime this stroll can be extremely pleasant, when the walls and towers are covered with ivy, the terraces carpeted with fresh grass, and the moat colourful with wild flowers and blossoming trees.

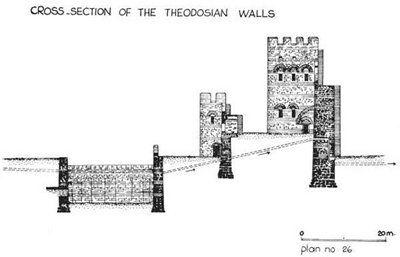

The land-walls were, for the most part, constructed during the reign of Theodosius II in the first half of the fifth century. The first phase of the Theodosian wall was completed in 413 under the direction of Anthemius, Prefect of the East. This consisted of a single wall studded with defence towers at regular intervals. However, in 447 a violent earthquake destroyed much of the wall, throwing down 57 defence towers. This happened at a very critical time, for Atilla the Hun was then advancing on Constantinople with his Golden Horde. Reconstruction of the wall began immediately under the direction of the new Prefect of the East, Constantine. The circus factions of the Hippodrome all worked together in one of their rare periods of cooperation, and within two months the walls had been rebuilt and were far stronger than before. For in addition to restoring and strengthening the original wall, Constantine added an outer wall and a moat. This stupendous achievement is commemorated by inscriptions in Latin and Greek on the Mevlevihane Gate, anciently known as the Gate of Rhegium. The Greek inscription merely gives the facts, the Latin one is more boastful; it reads: “By the command of Theodosius, Constantine erected these strong walls in less than two months. Scarcely could Pallas herself have built so strong a citadel in so short a span.” The pride is understandable, for the new defence walls saved the city from Atilla, the Scourge of God, who withdrew his forces and, instead, ravaged the western regions of the Roman Empire.

Even though they are in ruins, enough remains of the Theodosian walls to reconstruct their original plan. The main element in the defence system was the inner wall, which was about five metres thick at the base and rose to a height of 12 metres. This wall was guarded by 96 towers, 18 to 20 metres high, at an average interval of 55 metres; these were mostly square but some were polygonal. Each tower is generally divided into two floors which do not communicate with one another. The lower stories were used either for storage or for guardhouses; the upper rooms were entered from the parapet walk, which communicated by staircases with the ground and with the tops of the towers, where were placed engines for hurling missiles and Greek fire at the enemy. Between the inner and outer walls there was a terrace called the peribolos, which varied from 15 to 20 metres in breadth, and whose level was about five metres above that of the inner city. The outer wall, which was about two metres thick and 8.5 metres in height, also had 96 towers, alternating in position with those of the inner wall; in general these were either square or crescent-shaped in turn. Beyond this was an outer terrace called the parateichion, bounded on the outside by the counter-scarp of the moat which was a battlement nearly two metres high. The moat itself was originally about ten metres deep and 20 metres wide, and may have been flooded whenever the city was threatened. All-in-all it was a most formidable system of fortification – perhaps the most elaborate and unassailable ever devised. Had it not been for the invention of gunpowder and cannons these walls might never have been breached.

Most of the inner defence-wall and nearly all of its huge towers are still standing, although sieges, earthquakes and the ravages of time have left their scars. Although a few of the towers are relatively intact, most of them are split and shattered or have half-tumbled to the ground. The outer walls have been almost completely obliterated and the fragmentary remains of only about half of its towers can still be seen. Grass, bushes, vines and trees have everywhere overgrown the ruins and softened their outlines. There are little kitchen gardens and orchards flourishing in the moat and along the parateichion and the peribolos.

FROM THE MARBLE TOWER TO YED

İ

KULE

We will begin our tour in the south-western corner of the city, just beyond where we ended our last stroll in Samatya. Here the sea-walls along the Marmara joined the land-walls, anchored to them by the Marble Tower, the handsome structure which we see standing on a little promontory by the sea. This tower, 13 metres square at its base and 30 metres high, its lower half faced in marble, is unlike any other structure in the whole defence-system, and may have been part of an imperial sea-pavilion. Indeed the ruins beside it seem to indicate that it was part of a small castle. Beyond the tower there are the sunken remains of a mole which must have been part of the castle harbour.

A short way in from the shore highway, immediately to the north of the first tower of the inner wall, we see one of the ancient gateways of the city. This is called the Gate of Christ because of the laureate monogram XP above it. In the long stretch of the Theodosian walls there were only ten gates and a few small posterns. Five of the ten gates were public entryways and five were used by the military, such as the one which we see here (it was sometimes called the First Military Gate). The distinction was not so much in their structure as in the fact that while the public gates had bridges over the moat leading to the country beyond, the military gates did not, but gave access only to the fortifications. Until the end of the last century Stamboul was still a walled town and these gates were the only entryways to the city from Thrace, but in recent times the walls have been breached to permit the passage of the railway and of several modern highways. Nevertheless, nearly all the ancient city gates continue in use, as they have now for more than 15 centuries.

The first stretch of the Theodosian walls is rather difficult to inspect because of the obstacles presented by the railway and the various industries that are located here. But the stroll here is more pleasant than it was in times past, because in recent years the authorities have removed the noxious tannery that reeked here since early Ottoman times. As Evliya describes this malodorous tannery as it smelt in his time: “The overpowering reek prevents people of quality from taking up their abode here, but the residents are so used to the stench, that should they happen to meet any musk-perfumed dandy, the scent quite upsets them.”

The best route on the first part of this stroll is to walk along inside the walls from the Marmara highway as far as the railway; then, after crossing the tracks cautiously, one can walk along the highway outside the walls as far as the gate at Yedikule, where one can enter the city again.

YED

İ

KULE AND THE GOLDEN GATE

Yedikule, the Castle of the Seven Towers, is a curious structure, partly Byzantine and partly Turkish. The seven eponymous towers consist of four in the Theodosian wall itself, plus three additional towers built inside the walls by Mehmet the Conqueror. The three inner towers are connected together and joined to the Theodosian walls by four heavy curtain-walls, forming a five-sided enclosure. The two central towers in the Theodosian wall are marble pylons flanking the famous Golden Gate of Byzantium. The structure was never used as a castle in the usual sense, but two of the towers were used in Ottoman times as prisons; the others were used as storage places for a part of the State treasure.

To visit Yedikule we must first enter the city through a little gate just north of the castle. Though it was somewhat reconstructed in Turkish times, the Byzantine eagle above the arch on the inside proclaims its origins. This must always have been the public entrance to the city in this vicinity, as indeed it is today, for the Golden Gate itself seems to have been reserved for the emperor and for distinguished visitors and processions.

We enter Yedikule itself by a gate near the east tower; once inside the grounds we turn left to enter the tower. This is sometimes called the Tower of the Ambassadors, since in Ottoman times foreign envoys were often imprisoned there. Many of these unfortunates have carved their names and dates and tales of woe upon the walls of the tower in half a dozen languages. An inscription in French gives this advice in verse: “Prisoners, who in your misery groan in this sad place, offer your sorrows with a good heart to God and you will find them lightened.” The floors of the tower have fallen, but one climbs up by a staircase in the thickness of the wall. When at the top it is worthwhile walking around the

chemin de ronde

as far as the Golden Gate, for there is a fine view of the castle and the walls down to the sea, and, if it is spring, one finds a profusion of orchids, hyacinths and Roman anemones growing in the turf.