Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (30 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

The most distinctive aspect of the exterior of the Myrelaion is the array of half-cylindrical buttresses that project from the west façade and the sides of the narthex and naos, articulating the internal bay divisions. The dome sits on a high cylindrical drum penetrated by eight round-arched windows. The church and the funerary chapel beneath it are of the same design, namely the four-column type so common in the tenth and eleventh centuries, with a three-bay narthex to the west and to the east the apse flanked by the sacristy and the prothesis, the chapel where the Eucharist was kept.

The funerary chapel can be visited in the company of the imam. A fragmentary fresco can be seen in the bema, the lower part of a panel depicting a female donor kneeling before a standing figure of the Virgin Hodegitria.

The Rotunda was excavated in 1964–5 by R. Nauman and is described by Striker in his book on the Myrelaion. Its external and internal diameters are 41.8 and 29.6 metres, respectively, with walls of finely cut aslar blocks now standing to a maximum height of 3.4 metres. The roof was originlly supported by some 75 columns. The Rotunda seems to have been in ruins when Romanus decided to build his palace on its substructure, erecting his church and funerary chapel just next to it. During the excavations of 1964–6 a fragmentary sculpture in porphyry was discovered in the Rotunda by the Turkish archaeologist Nezih Firatl

ı

. Firatl

ı

showed that this fragment, which we have seen in the Archaeological Museum, was part of a foot of the group of the Tetrarchs that now stands outside the south-west corner of the Basilica of San Marco in Venice.

LALELI CAM

İİ

We now return to Ordu Caddesi where we are confronted by the imposing complex of Laleli Camii, built on a high terrace. This is a very frivolous mosque, perhaps the best of all the baroque mosques in the city. It was founded by Mustafa III and built between 1759 and 1763 by Mehmet Tahir A

ğ

a, the greatest and most original of the Turkish baroque architects.

Before we visit the mosque itself we might take a stroll through the galleries below it, a veritable labyrinth of winding passages and vaulted shops. In the centre, directly underneath the mosque, is a great hall supported on eight enormous piers, with a fountain in the centre and a café and shops round about. The whole thing is obviously a

tour de force

of Mehmet Tahir to show that he could support his mosque apparently on nothing!

The mosque itself is constructed of brick and stone, but the superstructure is of stone only; the two parts do not seem to fit together very well. Along the sides run amusing but pointless galleries, the arcades having round arches; a similar arcade covers the ramp leading to the imperial loge. The plan of the interior is an octagon inscribed in a rectangle, all but the western pair of supporting columns being engaged in the walls; the latter support a gallery along the west wall. All the walls are heavily revetted with variegated marbles, yellow, red, blue and other colours, which give a somewhat gaudy effect. In the west wall of the gallery there are panels or medallions of

opus sectile

, in which are used not only rare marbles but even semi-precious stones such as onyx, jasper and lapis lazuli. A rectangular projecting apse contains the mihrab of sumptuous marbles. The mimber is of the same materials, while the kürsü or preacher’s chair is a rich work of carved wood heavily inlaid with mother-of-pearl – altogether an extravagant and entertaining decor!

Like all of the other imperial mosques, Laleli Camii was surrounded by the many attendant buildings of a civic centre, some of which have unfortunately succumbed to time. On Ordu Caddesi there still remains the pretty sebil with bronze grilles and the somewhat sombre octagonal türbe in which are buried Sultan Mustafa III and his son, the unfortunate Selim III. On the terrace inside the enclosure is the imaret. This is an attractive little building with a very strange plan indeed, quite impossible to describe: it must be inspected. Unfortunately, the other institutions in the külliye – the medrese and the hamam – have disappeared.

The street just to the east of the mosque, Fethi Bey Caddesi, leads at the second turning on the left to a fascinating han which probably belongs to the Laleli complex. This was formerly known as Çukur Çe

ş

me Han

ı

, the Han of the Sunken Fountain, but its present residents call it Büyük Ta

ş

Han, the Big Stone Han. The plan of this too is almost indescribable. We enter through a very long vaulted passage, with rooms and a small court leading from it, and emerge into a large courtyard, in the middle of which a ramp descends into what were once the stables. Around this porticoed courtyard open rooms of most irregular shape, and other passages lead to two additional small courts with even more irregular rooms! One seems to detect in this the ingenious but perverse mind of Mehmet Tahir A

ğ

a. The han has now been restored and houses a restaurant and shops.

Leaving the han, we turn left and continue along Fethi Bey Caddesi for about 100 metres until it intersects Fevziye Caddesi; there we veer right and continue for another 100 metres until we come to

Ş

ehzadeba

ş

ı

Caddesi, where we turn left. The broad avenue on which we are now strolling follows the course of the ancient Mese, which turned to the north-west after leaving the Forum Tauri. The modern avenue takes its name from

Ş

ehzade Camii, the great mosque which we see looming up ahead. Before we visit the mosque, however, let us continue past it for a little way so as to look at two monuments of some minor interest.

THE BELED

İ

YE AND THE MEDRESE OF ANKARAVI

MEHMET EFENDI

Just past

Ş

ehzade Camii on the left side of the avenue we see the huge building of the Belediye, or Municipality, the headquarters of the civil government of Istanbul. Erected in 1953, it is of the glass and aluminium variety and not bad of its kind, except for a curious arched excrescence on the lower part of the building which looks like a hangar for airplanes. From the roof of the higher part, one has a fine view of the surrounding district. Behind this building is the little medrese of the

Ş

eyh-ül Islam Ankarav

ı

Mehmet Efendi, founded in 1707. This has recently been restored and is now used as part of the Economics Faculty of the University. It is a small and attractively irregular building, chiefly of red brick, with a long, narrow courtyard, at the far end of which is the lecture-hall reached by a flight of steps.

BURMAL

İ

CAM

İ

Crossing now to the opposite side of

Ş

ehzadeba

ş

ı

Caddesi, we find in front of the west wall of the

Ş

ehzade precinct a pretty little mosque, recently restored, called Burmali Cami. It was built about 1550 by the Kad

ı

(Judge) of Egypt, Emin Nurettin Osman Efendi. Although of the very simplest kind – a square room with a flat wooden ceiling – it has several peculiarities that give it a

cachet

of its own. Most noticeable is the brick minaret with spiral ribs, from which the mosque gets its name

(burmah =

spiral); this is unique in Istanbul and is a late survival of an older tradition, other examples of which are to be found at Amasya and elsewhere. Then the porch is also unique: its roof, which is pitched, not domed, is supported by four columns with Byzantine Corinthian capitals. The reuse of ancient capitals also occurred in the earlier architecture of Bursa and among the Selçuks, but it is very rare indeed in Istanbul. (Bayan Cahide Tamer, the architect who so ably restored the mosque, found the original Corinthian capitals so decayed and broken as to be unusable in the restoration, but she was able to find in the Archaeological Museum four others of the same type with which she replaced the originals.) Finally, the entrance portal is not in the middle but on the right-hand side. This is usual in mosques whose porches are supported by three columns only – so as to prevent the door being blocked by the central column – but here there seems no reason for it. The interior of the mosque has no special features.

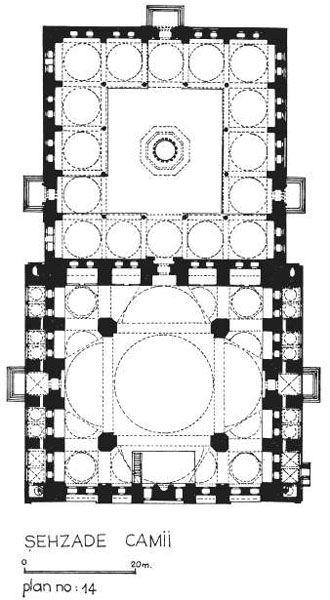

The great mosque of the

Ş

ehzade has been looming up before us for some time and we must now visit this magnificent complex systematically. The main entrances are on

Ş

ehzadeba

ş

ı

Caddesi. The complex consists of the mosque, several türbes, a medrese, a tabhane or hospice, a public kitchen and a primary school.

Ş

ehzade Camii, the Mosque of the Prince, was built by Süleyman the Magnificent in memory of his eldest son, Prince Mehmet, who died of smallpox in the 22nd year of his age in 1543. As Evliya Çelebi wrote of Prince Mehmet: “He was a prince of exquisite qualities and possessed of a piercing intellect and a subtle judgement. Süleyman, when laid up with the gout, had fixed on him in his mind to be a successor to his crown; but man proposes and God disposes; death stopped the way of that hopeful youth at Magnesia, from whence his body was brought to Constantinople.”

Süleyman was heartbroken at the death of his beloved son and sat beside Mehmet’s body for three days before he would permit burial to take place. When Süleyman recovered from his grief he determined to commemorate Prince Mehmet by the erection of a great mosque and pious foundations dedicated to his memory. Sinan was commissioned to design and build it and began work almost immediately, finally completing the project in 1548. Sinan himself called this his “apprentice work”, but it was the work of an apprentice of genius, his first imperial mosque on a truly monumental scale.

Sinan, wishing from the very first to centralize his plan, adopted the expedient of extending the area not by two but by four semidomes. Although this is the most obvious and logical way both of increasing the space and of centralizing the plan, the identical symmetry along both axes has a repetitive effect which tends towards dullness. Furthermore, the four great piers that support the dome arches are stranded and isolated in the middle of the vast space and their inevitably large size is thereby unduly emphasized. These drawbacks were obvious to Sinan once he had tried the experiment, and he never repeated it.

The interior, then, is vast and empty; almost alone among the mosques, it has not a single column; nor are there any galleries. Sinan has succeeded in minimizing the size of the great piers by making them very irregular in shape: contrast their not unpleasing appearance with the gross “elephant’s feet” columns of Sultan Ahmet. The general effect of the interior is of an austere simplicity that is not without charm: Milton’s very un-Horatian “plain in her neatness” might well describe it.

As if to compensate for this interior plainness, Sinan has lavished on the exterior a wealth of decoration such as he uses nowhere else. The handsome courtyard avoids the defect of that of the Süleymaniye (see Chapter 10) by having all four porticoes at the same height, at the expense of sacrificing to some extent the monumentality of the western façade. The

ş

ad

ı

rvan in the centre is said by Evliya to be a contribution of Murat IV. The two minarets are exceptionally beautiful: notice the elaborate geometrical sculpture in low relief, the intricate tracery of their two

ş

erefes, and the use of occasional terra-cotta inlay. The cluster of domes and semidomes, many of them with fretted cornices and bold ribbing, crowns the building in an arrangement of repetition and contrast that is nowhere surpassed. It was in this mosque, too, that Sinan first adopted the brilliant expedient of placing colonnaded galleries along the entire length of the north and south façades in order to conceal the buttresses, an arrangement which, as we will see, he used with even greater effect at the Süleymaniye: here the porches have but one storey, while at the Süleymaniye they have two. This is certainly one of the very finest exteriors that Sinan ever created; one wonders why he later abandoned, or at least greatly restrained, these decorative effects.