Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (27 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

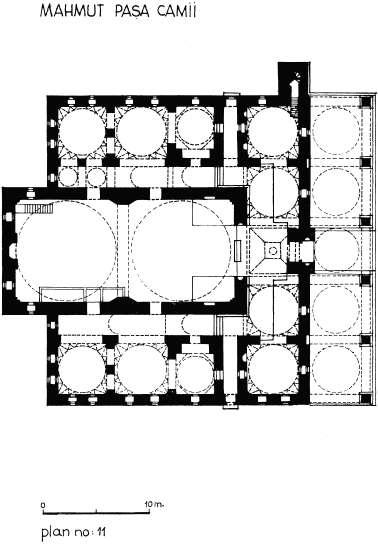

The two large domes of the great hall of the mosque have smooth pendentives, rather than the stalactited ones usually found in these early mosques. The mihrab and mimber and in general all the decoration and furniture of the mosque are eighteenth century or later and rather mean in appearance. This is a pity since it gives the mosque a rather unattractive aspect, so that one finds it difficult to recapture its original charm. In the small side-chambers some of the domes have smooth pendentives while others are stalactited. The function of these side-rooms, almost universal in mosques of this type, was for long a puzzle. The solution has been provided by Semavi Eyice, who shows that they were used, here and elsewhere, as a tabhane, or hospice, for travelling dervishes.

Leaving the mosque, we retrace our steps to the intersection outside the courtyard. There, down a short alley on the left, we see a little graveyard in which stands Mahmut Pa

ş

a’s magnificent and unique türbe. The türbe is dated by an inscription to A.H. 878 (A.D. 1474), the year in which the unfortunate man was executed. It is a tall octagonal building with a blind dome and two tiers of windows. The upper part of the fabric on the outside is entirely encased in a kind of mosaic of tile-work, with blue and turquoise the predominating colours. The tiles make a series of wheel-like patterns of great charm; they are presumably of the first Iznik period (1453–1555), and there is nothing else exactly like them in Istanbul.

Leaving the türbe, we take the narrow street directly opposite, K

ı

l

ı

çç

ı

lar Soka

ğ

ı

, the Street of the Sword-Makers. This is one of the most fascinating byways in the city, and is one of the very few surviving examples of an old Ottoman bazaar street. The left side of the street is lined with an arcade of ancient shops which were once part of the külliye of Nuruosmaniye Camii. On the right side of the street we pass a number of shops and ateliers which are part of the Çuhac

ı

lar Han

ı

, the Han of the Cloth-Dealers. The Çuhac

ı

lar Han

ı

was built in the first half of the eighteenth century by Damat Ibrahim Pa

ş

a, Grand Vezir in the reign of Sultan Ahmet III. It is not as grand as some of the other old hans in this neighbourhood; nonetheless it adds to the distinctively Ottoman character of the surrounding streets. We enter the han through an arched gateway halfway down the street and find ourselves in the cluttered inner courtyard, which is lined with an arcade of shops and ateliers. If we leave the han by the portal in the far left-hand corner, we will find ourselves just opposite one of the gates of the Kapal

ı

Çar

ş

ı

. We turn right here and after a few steps we pass through an arched gateway over the street and enter Mahmut Pa

ş

a Yoku

ş

u, one of the principal market streets of Stamboul.

About 250 metres down Mahmut Pa

ş

a Yoku

ş

u, we come to a turning on the left where we see an imposing domed building. This is a part of the Mahmut Pa

ş

a Hamam

ı

, one of the two oldest baths in the city, dated by an inscription over the portal to A.H. 871 (AD. 1476). (The Gedik Ahmet Pa

ş

a Hamam

ı

, described in Chapter 7, may possibly be a year or so older, but it is not dated.) This was originally part of the Mahmut Pa

ş

a Külliyesi, and, as always in these interdependent pious foundations, its revenues went to the support of the other institutions in the complex. Like most of the great hamams, it was originally double, but the women’s section was torn down to make room for the neighbouring han. We enter through a large central hall (17 metres square) with a high dome on stalactited pendentives; the impressive size of the camekân is hardly spoiled by the addition of a modern wooden balcony. The so

ğ

ukluk is a truly monumental room covered by a dome with spiral ribs and a huge semidome in the form of a scallop shell; on each side are two square cubicles with elaborate vaulting. The hararet is octagonal with five shallow oblong niches, and in the cross-axis there are two domed eyvans, each of which leads to two more private bathing cubicles in the corners. Like all of Mahmut Pa

ş

a’s buildings, his hamam is a very handsome and well-built structure. For a time it fell into disuse and then served as a storage depot, but it has been restored and now serves as a market hall.

On leaving the hamam a somewhat complicated detour leads to an interesting monument. We take Sultan Oda Soka

ğ

ı

, the street which leads off to the right from Mahmut Pa

ş

a Yoku

ş

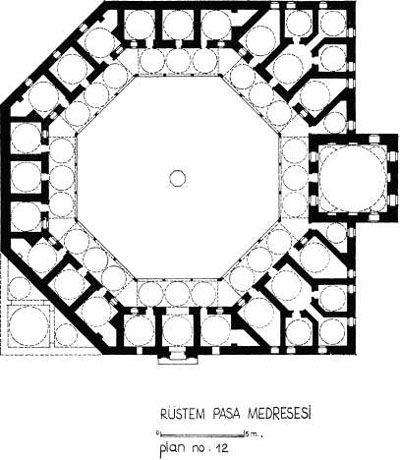

u directly opposite the hamam, and follow it for about 200 metres to its end; then we turn left and then left again at the second turning. This brings us to the medrese of Rüstem Pa

ş

a, designed by Sinan and erected, according to an inscription, in 1550. It has a unique plan for a medrese. The courtyard is octagonal with a columned portico of 24 domes and a

ş

ad

ı

rvan in the centre. Behind this the cells are also arranged in an octagonal plan, but the building is made into a square on the exterior by filling in the corners with auxiliary rooms – baths and lavatories. One side of the octagon is occupied by the lecture hall, a large domed room which projects from the square on the outside like a great apse. This fine and unique medrese has been beautifully restored.

BYZANTINE SUBSTRUCTURE ON

CEMAL NADIR SOKA

Ğ

I

From here we can extend our detour to another interesting monument nearby. (This is part of the charm and trouble of strolling through Istanbul: one is continually being diverted by the prospect of another fascinating antiquity around the next corner.) Leaving the medrese, we retrace our way for a few steps and take the first turning on the left. This almost immediately brings us to a step street, Hakk

ı

Tar

ı

k Us Soka

ğ

ı

. At the bottom of the steps we turn left on Cemal Nadir Soka

ğ

ı

and immediately to our left we see a massive retaining wall with two iron doors and barred windows. (The doors are locked, but can usually find a local who has the key.) This is perhaps the most astonishing Byzantine substructure in the city, consisting of a congeries of rooms and passages, 12 in all, every size and shape. There is a great central hall, 16 by 10.5 metres in plan and about six metres high, whose roof is supported by two rows of six columns, with simple but massive bases and capitals. From this there opens another great room, 13 by 6.7 metres, that ends in a wide apse. A series of smaller chambers, one of them oval in shape, opens from each of these large rooms and from the passages that lead off in all directions. The whole thing is like an underground palace and must clearly have been the foundation of something very grand indeed. However, all attempts to identify this structure with some building mentioned in Byzantine literature have been inconclusive.

We now retrace our steps back to where our detour began, outside the Mahmut Pa

ş

a Hamam

ı

. There we continue downhill along Mahmut Pa

ş

a Yoku

ş

u to look at some of the old hans which line the streets of this neighbourhood. There are literally scores of ancient hans in this district. Evliya Çelebi mentions by name more than 25 that already existed by the middle of the seventeenth century, and many others were built during the next 100 years; some go back to the time of the Conquest and many are built on Byzantine foundations.

KÜRKÇÜ HANI

About 100 metres downhill from the Mahmut Pa

ş

a Hamam

ı

we see an arched gateway on the left side of the street; this is the entrance to the Kürkçü Han

ı

, the Han of the Furriers. This, too, is a benefaction of Mahmut Pa

ş

a and is the oldest surviving han in the city. Unfortunately, part of it is in ruins or has disappeared and the rest is dilapidated and rather spoiled. Originally it consisted of two large courtyards. The first, nearly square, is 45 by 40 metres, and had about 45 rooms on each of its two floors; in the centre was a small mosque, now replaced by an ugly block of modern flats. The second courtyard to the north was smaller and very irregularly shaped because of the layout of the adjacent streets. It had about 30 rooms on each floor and must have been very attractive in its irregularity; unfortunately it is now almost completely ruined.

BÜYÜK YEN

İ

HAN AND KÜÇÜK YEN

İ

HAN

Leaving the Kürkçü Han

ı

, we continue down Mahmut Pa

ş

a Yoku

ş

u and turn left at the next street, Çakmakç

ı

lar Yoku

ş

u. Just beyond the first turning on the left, we come to a massive gateway which leads to another Ottoman han: this is the Büyük Yeni Han, which means literally the Big New Han. It is called new because it was built in 1764, just a youngster in this ancient town, and big because it is: the second largest in the city after the Büyük Valide Han, which we will see presently

.

Its great courtyard must be over 100 metres in length but very narrow and tall. Unfortunately, it has been divided in the middle by what appears to be a later construction which much diminishes its impressive length. Nevertheless, its three storeys of great round-arched arcades are very picturesque. It was built by Sultan Mustafa III and is one of the best extant examples of the baroque han.