Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists (3 page)

Read Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists Online

Authors: Scott Atran

But what is it that binds imagined kin into a “band of brothers” ready to die for one another as are parents for their children? That gives nobility and sanctity to personal sacrifice? What is the cause that co-opts the evolutionary disposition to survive?

NATURE AND NURTURE

That afternoon I began posing “switched-at-birth” scenarios to Farhin and his brother mujahedin on whether the children of Zionist Jews raised by mujahedin families since birth would become good Muslims and mujahedin or remain Zionist Jews. Nearly all mujahedin, leaders and foot soldiers alike, answered that the children would grow up to be good Muslims and mujahedin. They usually said that everyone’s

fitrah

(nature) is the same and that social surroundings and teaching make a person good or bad. This is how the alleged emir (leader) of Jemaah Islamiyah, Abu Bakr Ba’asyir, put it in an interview that I conducted with him in Cipinang prison in Jakarta:

Environment can change people’s

fitrah

—nature. Human beings have an innate propensity to

tauhid

—to believe in the one true God. If a person is raised in a Jewish environment, he’ll be Jewish. But if he’s raised in an Islamic environment, he’ll follow his

fitrah

—nature. Human beings are born in

tauhid,

and the only religion which teaches and nurtures

tauhid

is Islam. As I said, according to Prophet Mohammed, the only things that can change a child into becoming Jewish or Christian are his parents or his environment. If he is born in an Islamic environment, he’ll survive. His

fitrah

is safe. If he is born in a non-Islamic environment, his

fitrah

will be broken and he can be a Jew or a Christian. Human beings have

tauhid

since birth. However, in their life’s journey they could have an epiphany to be devout Muslims. In contrast, a Muslim who fails to resist the devil’s temptation can become an apostate.

American white supremacists and members of the Christian Identity movement, when asked the same question, more often give a different answer: Jews are born bad and always will be bad. It’s an essentialist take on human nature, of the biologically irreversible kind, that underlies a history of racism in the West.

Shortly before the last run that day of our hypothetical scenarios, Rohan Gunaratna, a Sri Lankan who heads a program in terrorism studies out of Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, received a text message on his cell phone from an informant in another

laskar

saying that I was to be “eliminated” that evening after dark. Rohan had helped me arrange entry into Poso, running interference with the Indonesian government and some of the mujahedin commanders who occasionally “consulted” for him. “Don’t worry, my friend,” he said, bobbing his head left and right. “We’ll get out of town before sundown. But this gives you time for a few more interviews.” With a grin like a Cheshire cat’s, he can sling his arms around the shoulders of killers and be calming. He’d make a good politician.

The previous day, a former mujahedin commander named Atok had warned me: “Don’t go up to Poso, our people shoot whites on sight. I would have shot you dead myself last year. But killing whites or Christians is not the best way to defend Islam.” I told him this change of heart was a relief, and he smiled wryly. Atok was tough as nails, but he positively melted when describing how finger-lickin’ good the chicken was at the Makassar Kentucky Fried Chicken, a favorite eatery and planning spot for Sulawesi’s top jihadis. Farhin and Rohan agreed that if we left at night and I sat between them in the backseat, I would be OK, and I trusted them. My guess is that one of the leaders of the Muslim charities I had been talking with didn’t want me snooping around anymore. The charities, like Kompak and even the local Red Crescent (the Islamic equivalent of the Red Cross) are very much involved in the sectarian fighting and sport their own militias.

Atok, a former commander of Muslim militia in Poso: “I don’t shoot whites on sight anymore.”

I came into Sulawesi as a French citizen (I’m a U.S. citizen too, but mujahedin don’t much like talking to Americans these days), but the text message implied that I had been Googled, which meant that whoever was after me knew that I was an American working on terrorism. Google can be a real bummer for anyone who wants to do fieldwork on the subject. I now have about twenty-four hours on the ground before someone does some Internet surfing and doesn’t like what he reads about me. It’s a new dimension of “fasttrack anthropology” for me, academically so frustrating, but I’ve also learned a lot in a day.

On the wooden deck of the restaurant where I was doing my interviews, overlooking a pastel seascape framed by low green hills, a radio was chanting sorrowful Koranic verses while two lovely young girls, their doe eyes framed by veils, fidgeted with a hi-fi belching out early Beatles. Dusk was coming and my pulse was racing. I’d started smoking kretek clove cigarettes to calm down, although I’m no smoker. Strange how the light at day’s end also calms and leads to reflection, especially in this soft evening air. I found myself back with my grandmother at a Beatles concert at New York’s Shea Stadium in the summer of 1965 with Ringo singing “Act Naturally,” then in the spring of 1971, when she stood up in the audience and yelled at Margaret Mead during a lecture at the American Museum of Natural History: “Why don’t you leave my grandson alone and let him be a doctor! Now you’ll get him cooked by cannibals!”

There’s a daredevil high to this sort of fieldwork, a feeling similar to what war correspondents feel, or at least those I’ve interacted with. Many people just pretend that dangerous and exciting things happen to them. I guess I share with some reporters not merely a dream of adventure, but an irresistible urge to live my dream and accomplish something by it, if only in witnessing what others cannot see but should.

But this line of work has its nightmarish moments. My interpreter, Huda, broke my reverie when he told me he’d been questioning a “retired” commander of Laskar Jihad, one of the first outside jihadi groups to come to Poso. “He said if a Christian would be raised by the mujahedin, the person would turn out fine, but a Jew comes from hell and is always a Jew.” That was the first time in Indonesia I had gotten that response. But the real stunner came next: “And he asked me if

you

are a Jew.”

“So what did you tell him?” I asked, aware what the answer would be but hoping it wouldn’t.

“I told him we’re all brothers in this world, so what does it matter if you’re a Jew?”

As the

laskar

commander trained his gaze on me, I said in light and measured tones: “Phone the car now, in English, like you’re asking for a cup of coffee.” I excused myself to go to the bathroom … and out the back door. It was sundown, and I was silently cursing up a storm for the mess I’d gotten myself into—for the umpteenth time vowing that I’d just stay home and tend my vineyards from now on—when Farhin and Rohan pulled up and I hightailed it out of there.

We bounced through the dusk along a pothole-loving road to the Christian town of Tentene, arriving on a beautiful night: the flat silhouette of Tentene’s surroundings made haunting by the sounds of night birds and tales of the

laskar.

The plan was to interview the clergyman in charge of the Central Sulawesi Christian Church, Rinaldy Damanik, a Batak from Sumatra. Farhin had fought and killed many Christians, but he now put on a shirt with flower patterns and sprinkled himself with cologne because … well, every red-blooded jihadi knows how wanton Christian girls are. I wondered if they would sense the bit of death that lingers about Farhin, or just his streak of the comic.

The Reverend Damanik had been arrested after the initial bout of sectarian violence in the region and taken to Jakarta. There he shared prison quarters in succession with Sayem Reda, one of Al Qaeda’s master filmmakers; with Imam Samudra, the convicted operations chief of the October 2002 Bali bombings; and with Abu Bakr Ba’asyir, the emir of Jemaah Islamiyah.

Damanik told me how he managed to sneak a Koran in to Sayem Reda after prison authorities had denied him one. “He thanked me and cried,” Damanik said. “He wasn’t really a bad man at heart.” Damanik also spent long hours with Imam Samudra, agreeing that the State was corrupt, but “I said to him that fighting corruption and abuse by killing tourists and people who had harmed no one was gravely wrong in his God’s eyes and mine. Imam Samudra said to me, as a joke or maybe not, that it’s a shame we didn’t meet and talk first, before the Bali bombing, when together we might have come up with a better strategy to change the government.”

I especially wanted to hear how the reverend and the emir got along, and also to get the former’s reaction to a ridiculous tale told on the Muslim side about the

kupukupu

(butterfly) battalion of bare-breasted Christian women who would wiggle at the Muslim men and lure them to their deaths. My jaw dropped into the coffee cup when the Rev. Damanik casually asked, “Would you like to meet one of the butterflies?” It turns out that they danced their own men to war, albeit with covered breasts. They even called themselves the Butterfly Laskar. Over time, Muslims and Christians have formed a whole zoo of

laskars

that reflect one another’s fantasies and fears: the

laskar labalaba

(spider army),

laskar man-goni

(bird army), the

laskar kalalaver

(bat army) that struck terror in the night.

I was even more surprised when Damanik told me how he had enjoyed the company of Ba’asyir, whom he sincerely respected. How Ba’asyir’s wife regularly brought them both fruit and seemed worried about the reverend’s health. Ba’asyir would confirm in the Cipinang Prison interview that the respect was mutual and strong, although he qualified the friendship that any Muslim could properly offer

kuffar

(infidels):

Yes, I was visited and was respected by him. I have a plan, if Allah allows me, to pay a visit to his house. That’s what I called

muamalah dunia

—daily relations in the secular life. Because Al Koran article sixty, verse eight says that “Allah encourages us to be kind and just to the people who don’t fight us in religion and don’t help people who fight us.” It means that we can help those who aren’t against us. On these matters we can cooperate, but we also have to follow the norms of Sharia…. So it is generally allowed to have business with non-Muslims. We can help each other; for example, if we are sick and they help us, then, if they become sick, we should help them. When they die we should accompany their dead bodies to the grave though we can’t pray for them.

Abu Bakr Ba’asyir had formally associated himself with Osama Bin Laden in 1998 (though he denied it and said the letter I had proving it so with his signature was a Mossad-CIA forgery). In 2003, Ba’asyir had been accused of plotting the assassination of then-Indonesian president Megawati Sukarnoputri and of helping to mastermind the 2002 Bali bombings. Ustaz (Teacher) Ba’asyir, as the other inmates and prison authorities reverently called him, was acquitted of both charges. I asked Ba’asyir (via an interpreter) the same sorts of questions about martyrdom and “rational choice” that I had asked would-be Palestinian martyrs and the Poso mujahedin. For example: “Would it be possible for an act of martyrdom to be aborted if the same results can be assured by other actions, like a roadside bomb?”

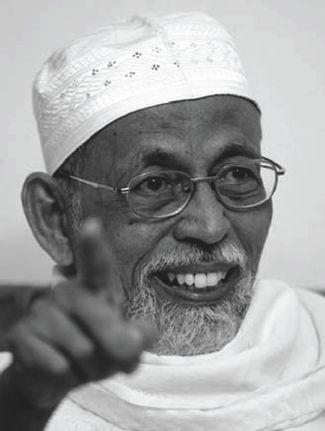

Abu Bakr Ba’asyir, alleged emir of Jemaah Islamiyah.

Other books

The Only Boy For Me by Gil McNeil

The Superhero's Son (Book 1): The Superhero's Test by Flint, Lucas

Dead Souls by Michael Laimo

Health At Every Size: The Surprising Truth About Your Weight by Linda Bacon

Counted With the Stars by Connilyn Cossette

This Is a Book by Demetri Martin

El juego de Sade by Miquel Esteve

078 The Phantom Of Venice by Carolyn Keene

One Good Turn: A Natural History of the Screwdriver and the Screw by Rybczynski, Witold

Breaking Her Rules by Katie Reus