Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists (4 page)

Read Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists Online

Authors: Scott Atran

Ba’asyir was the portrait of a self-assured man. He was surrounded by numerous acolytes, including convicted Jemaah Islamiyah bombers, and by prison guards who showed him deference and let him preach as he pleased from his hawk’s roost. Between the white skullcap and the knee upon which rested his chin, there were sprigs of mostly salt and some pepper hair, large spectacles, and a toothy grin that exuded vulpine gentility. I was booted out of the prison: “No whites now, too many coming in,” I was told. So I conducted the interview over two days by text-messaging my interpreter, Taufik, who was inside with a tape recorder.

This is a parable Ba’asyir told Taufik:

If there are better ways to carry out an action and we don’t have to sacrifice our lives, those ways must be chosen. Because our strength can be used for other purposes. The reason the

ulema

[learned clergy] allow this comes from a story of the Prophet Mohammed.

There was a young man who received magic training to be one of King Fir’aun’s magicians. Kings in the past had magicians. [Former Indonesian president] Suharto had many. When this magician became an old man, he was asked to find a replacement. In his search, he met a priest and learned from him.

He became a better magician after learning from the priest rather than from other magicians and started to spread the word, and he received the ability to heal blind people. He healed many people, including King Fir’aun’s blind minister.

Then, when this minister was able to see again, he offered to fulfill any request in his power that the magician might make. The magician replied that he hadn’t healed the minister, Allah had. “He is my lord and your lord. If you want to be cured and you admit the existence of Allah, you will be cured.” Then the minister went to his office.

King Fir’aun asked him, “Who has cured you?”

“The one who cured me was Allah.”

“Who’s Allah?”

“Allah is my God.”

Fir’aun was angry and tortured the minister, who admitted that he was told this by the magician who had healed him. Then this magician was told that he would be forced to abandon his conviction and to stop his activity. But this was a matter of principle for the magician, who did not want to abandon his conviction.

Many people tried to assassinate the magician. Finally, the magician said that if King Fir’aun wants to kill him, it’s easy. What Fir’aun needs to do is to gather many people in a field, put the magician in the middle, and shoot arrows into his body. But before doing that they must say, “Bismillah” [In the name of God]. When the arrows finally struck the magician, he died, but his mission to spread the word of Islam was accomplished. From this story, many

ulema

[clerics] agree to allow martyrdom actions as long as such actions will bring many benefits to the Islamic

ummat

[communities].

In The

Descent of Man,

8

Charles Darwin wrote:

The rudest savages feel the sentiment of glory…. A man who was not impelled by any deep, instinctive feeling, to sacrifice his life for the good of others, yet was roused to such action by a sense of glory, would by his example excite the same wish for glory in other men, and would strengthen by his exercise the noble feeling of admiration…. It must not be forgotten that although a high standard of morality gives but slight or no advantage to each individual man and his children over other men of the same tribe, yet that an increase in the number of well endowed men in the advancement of the standard of morality will certainly give an immense advantage of one tribe over another tribe.

Glory is the promise to take life and surrender it in the hope of giving greater life to some group of genetically bound strangers who believe they share an imagined community under God (or under His modern secular manifestations, such as the nation and humanity). It’s the willingness of at least some to give their last full measure of devotion to the imaginary that makes the imaginary real, a waking dream—and for others, a waking nightmare.

CHAPTER 2

TO BE HUMAN: WHAT IS IT?

Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, Or what’s a heaven for?

—ROBERT BROWNING, “ANDREA DEL SARTO,” 1855

O

n a second-floor walkup off a narrow alley in Gaza’s Jabaliyah refugee camp, I came to interview the family of Nabeel Masood. The neighborhood knew Nabeel as a kind and gentle boy, but he changed after the death of his two favorite cousins, who were Hamas fighters. No one remembers him wanting revenge for their deaths so much as a meaning. There had already been more than a hundred Palestinian suicide attacks before March 14, 2004, when Nabeel and his friend Mahmoud Salem from Jabaliyah, both of them eighteen, were dispatched by Muin Atallah (an officer in the Palestinian Preventive Security Service). Their mission, arranged jointly by Hamas and Fateh’s Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigades, was to attack the nearby Israeli port of Ashdod. Security officials believe the two were sent to launch a 9/11-style mega-terrorist attack and blow themselves up near the port’s bromine tanks.

Had they succeeded in this, the effects could have been devastating, with poisonous gases spreading to a 1.5-kilometer radius, killing thousands within minutes. As it was, they killed themselves and eleven other people. On March 22, 2004, Israel retaliated by assassinating Hamas founder and spiritual leader Sheikh Ahmed Yassin with rocket fire from a gunship as he was leaving a Gaza City mosque. Yassin’s successor as leader of Hamas, pediatrician Dr. Abdel Aziz al-Rantisi, called the Ashdod bombers heroes and promised more attacks like it. An Israeli missile struck him down in Gaza on April 17, 2004.

Nabeel Masood’s mother was crying softly and reading a letter when I walked in the door. She handed me the letter (written in English).

Letter of Appreciation and Admiration

Mr. and Mrs. Masood, it gives me great pleasure to inform you that your son Martyr Babeel

[sic],

has been doing well in English during the period he has spent in the 11th grade, call 3. He has passed his tests successfully. The thing I really appreciate. He was first in his class. He was distinguished not only in his hard studying, sharing, and caring, but also in his good morals and manhood. I would really like to congratulate you for his unique success in both life and the hereafter. I would like to thank from the bottom of my heart all who shared in building up Nabeel’s character. You should be proud of your son’s martyrdom.

With all my respect and appreciation.

Mr. Ismael Abu-Jared

The evening before he died, he had gone to the mosque, where he sat quietly alone for hours, then visited his friends in the neighborhood and came home. I asked Nabeel’s father: “Do you think the sacrifice of your son and others like him will make things better for the Palestinian people?”

“No,” he said. “This hasn’t brought us even one step forward.”

The boy’s mother only wanted back the pieces of her son’s body. His father had emptied the house because it is Israel’s policy to destroy the family home of any

shaheed,

or holy warrior, although he and his wife would have done anything to stop their son if they had known. “It can’t go on like this,” the father lamented. “There can only be two states, one for us and one for the Israelis.”

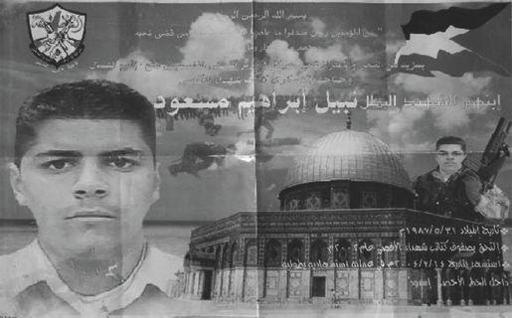

AI Aqsa Martyrs Brigade poster of Nabeel Masood, Ashdod suicide bomber.

I asked if he was proud of what his son had done. He showed me a pamphlet, specially printed by Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigades and endorsed by Hamas, praising the actions of his son and the two other young men who accompanied him.

“My son loved life. Here, you take it.” He pushed the pamphlet into my hands. “Burn it if you want. Is this worth a son?”

Outside in the narrow street, kids were playing fast-paced, acrobatic soccer off the high house walls, some marked with fading, ghostlike posters of the Martyr Nabeel. “What do you feel about what Nabeel did?” I asked.

“His courage will make us free!” exclaimed a boy, kicking the ball. Another boy echoed his words and gave a ferocious kick back.

Nabeel was, for one flaming moment, the hero every boy here wanted to be.

This kind of courage to kill and die is not innate. It’s a path to violence that has to be cultivated and channeled to a target. The culture of violent jihad is the landscape on which the path is trodden. Fellow travelers—mostly friends and some family—walk and furrow the path together. They leave pheromone-like tracers for those who come after, letters of love for their peers and heroic posters and videos with the thrill of guns and personal power made into an eternally meaningful adventure through sacred-book-swearing devotion to a greater community and cause.

I returned to Israel on a Friday evening. Unlike Jerusalem, which is quiet on the Jewish Sabbath, Haifa atop Mount Carmel was alight. Joyful groups of high school girls were scurrying everywhere. I asked three hitchhikers who were holding hands, just as my daughters do with their friends, if anything special was up. “Yes,” one girl said, very sweetly. “You’re not from Haifa; you see, it’s a weekend and holiday, and no school!” Hamas leaders contend that these young girls, too, merit death because they will become Israeli soldiers. The Hamas weekly,

Al Risala,

proclaimed in an editorial that “martyrs are youth at the peak of their blooming, who at a certain moment decide to turn their bodies into body parts—flowers.” In a moment of naive epiphany, I felt that if this blossoming young woman could just spend a little time with one of these young men from Gaza neither would need to die. But the wall grows between them each passing day, blocking all human touch.

Then I remembered something Nabeel’s father had said. I had written it down, but it hardly registered at the time: “My son didn’t die just for the sake of a cause, he died also for his cousins and friends. He died for the people he loved.” And my puzzling over that sentiment then became an overarching theme of study for this book.

BALTIMORE, OCTOBER 1962-NOVEMBER 1963

The day after President Kennedy’s October 22, 1962, Cuban missile crisis speech, I asked my mother, as she drove me home from school, what it was all about. I remember hearing the president talk about getting ready for “danger” and “casualties” but also a “God willing” to see things turn out right. “Ask your father when he gets home,” she said. I knew this time it wasn’t just me in trouble.

The next morning in school we had a “duck and cover” drill: A siren went off over the school intercom and we scurried under our desks with hands over our heads to protect ourselves from the flying glass an exploding atom bomb would surely produce. A new world war, I imagined, wouldn’t be much different from the one my father had been in. But because of atom bombs, I thought it would be a fast war that my family could survive inside a big steel filing cabinet with some water and an air hole. In the house we had an old copy of the

Life

magazine article, “H-Bomb Hideaway.” Only $3,000!

I heard my father’s car pull into the driveway. I remember very clearly—as clear as an old memory can be—my heart pounding as I asked: “Dad, is there going be an atomic war?” He looked at me with a strained but loving smile and ruffled my hair as he had when he told me that my baby brother, Harris, had been in a car accident and was in the hospital. “Only about a 20 percent chance, son.” (Many years later my father told me that during the crisis he had been asked to determine whether F-4 Phantom jets armed with Sparrow missiles could knock down Soviet nuclear missiles launched from Cuba. The answer: no.)

In

Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis,

Graham Allison and Philip Zelikow note that some interpreters of the Cuban missile crisis offer assurances to readers that “rational actors” worked predictably within an efficient “organizational behavioral paradigm” to save the day.

1

Hardly. Perusing the ExComm tapes, you do get an impression in hindsight that Jack and Bobby Kennedy were two of the only reasonable characters around. Not because they were clear about what was to be done, but because they were terribly unsure that the unassailably logical arguments for going to war were sane. If the president had listened to the generals and hawks—the ones with the best security credentials—then the Cubans, the Russians, and a great many of us would have been blown to kingdom come.

2

It was because the president and his brother cajoled an officer to delay word of the U.S. spy plane under his command having been shot at over Cuba that standard “rules of engagement” to massively retaliate weren’t triggered. Unbeknownst to the Americans, Soviet submarine B-59 also happened into history, armed with nuclear torpedoes that the ship’s commander, Valentin Savitsky, had targeted on a U.S. Navy vessel.

3

But chance and luck put Vasily Arkhipov, the sub’s chief of staff, on board, and it was he who, in most versions told, calmed the commander and spared the world.

4

Other books

A Perfect Home by Kate Glanville

Thomasina - The Cat Who Thought She Was God by Paul Gallico

Pickin' Murder: An Antique Hunters Mystery by Vicki Vass

Conquered: She Who Dares Book Two by LP Lovell

Lawless: Mob Boss Book Three by Michelle St. James

Life in the Lucky Zone (The Zone #2) by Patricia B. Tighe

MJ by Steve Knopper

Lillian Holmes and the Leaping Man by Ciar Cullen

Dark God by T C Southwell

The O’Hara Affair by Thompson, Kate