Talking with My Mouth Full (12 page)

Read Talking with My Mouth Full Online

Authors: Gail Simmons

Through Jeffrey, I had also come to know Daniel Boulud, the iconic French chef who ruled the Upper East Side. We’d worked on a couple of stories with him, and Jeffrey dined at Daniel as often as possible. So I paid him a visit to see if he could offer any advice.

Daniel Boulud is charming and larger than life. The few times I had been in a room with him, I was mesmerized by his charisma. His marketing director, Georgette Farkas, was always generous with me, too. She seemed to appreciate the job I did keeping Jeffrey on track.

I wanted to meet with Daniel and Georgette, if only to pick their brains. After all, they were infinitely connected and the food world worshipped them. Georgette said, “I wish we could hire you. I’m drowning. We have three book projects in the works. I need help on our restaurant openings, public relations, marketing and special events, Daniel’s travel . . . But we can’t afford to hire anyone right now.”

They put me in touch with Dorie Greenspan, a contributing editor at

Bon Appétit

and esteemed cookbook author. Among her many accomplishments: she had written Daniel’s

Café Boulud Cookbook

and the English version of

Chocolate Desserts

by Pierre Hermé, a man viewed by many as the single greatest pastry chef in the world. She gave me great advice and put me in touch with a cookbook editor at Simon & Schuster, who offered me a job as an assistant editor. But still no visa. It just wasn’t working.

Frustrated and tired of my dismal prospects in New York, I decided to take a ten-day vacation to visit friends in Los Angeles and San Francisco and catch my breath. It was the first vacation I’d taken on my own in many years. On the last few days of my trip I noticed that my glands were swollen and my throat was extremely sore. I flew back to New York on Christmas Eve. When I got out of bed on Christmas Day, Jeremy gasped, “What’s wrong with you?”

My body was covered in small red dots. I had a fever. We called my doctor, but no one was around. We had to go to the ER. It was a virus, but no one knew what it was. I was sick. My visa was expiring. I had no job. I flew home to Toronto. It took six weeks to get better. It turned out I had Epstein-Barr virus—the Jewish cousin of mononucleosis, but angrier.

This was another living-in-my-parents’-basement moment.

Meanwhile, I had left Jeremy in New York, finishing his master’s degree and working part-time at a record label.

Toward the end of my recovery in Canada, I got a call from Jeffrey saying he’d received a message on his answering machine. He liked to screen his calls. He never deleted the messages, and his machine was always full. Somehow, Georgette from Daniel’s office had gotten through saying she was trying to contact me. I called her back immediately.

“We’re ready to hire now. Are you free?”

The sky opened up and the culinary angels started singing. Again.

“I am so free,” I said. “You have no idea how free I am. But . . . I need a visa.” I dropped the V bomb and held my breath.

“Oh, that’s no problem,” she said casually.

A substantial portion of Daniel’s kitchen was in the United States on a visa as well. Many employees were Mexican or Somali. Many were European: French, Swiss, Austrian, or Belgian. There were a few Japanese and one or two Americans thrown in for good measure. They had an immigration lawyer on retainer.

I was going back to New York.

Champagne on Arrival

THE SMELL FROM

the baker’s oven next door wafts into my office, and I walk over for another butter roll. Each one is a little bigger than a golf ball, with a perfect cube of butter and a pinch of flaky gray sea salt buried deep in the center. I bite into the warm dough, and find the salty, buttery core. It’s made from the most humble ingredients of all: flour, water, butter, salt. But in a master’s hands, they become the most exquisite, most luxurious midday snack in the world.

The entire front-of-house staff at Daniel’s restaurant would assemble in the dining room every night, six days a week, at 5 p.m., before dinner service. At this meeting, Daniel Boulud or his chef de cuisine would talk about the night’s specials. It was the calm before the storm.

Standing around were up to fifty people, including the runners and busboys, the maître d’s, captains, assistant captains, and reservationists—an army, perfect in their uniforms. Daniel has 110 seats in the dining room, so the ratio is close to two to one, diners to service staff.

Michael Lawrence, the then general manager, would read through the list of reservations: “Bruno, in your section you have Howard Stern at table 25 and Bill Cosby at table 19.”

The reservation chart was tagged with levels of VIP. On these kinds of lists, importance is usually designated by X’s: “PX,” “PXX.” Some names may have the term “COA” beside them; this stands for “champagne on arrival.”

Michael would end every meeting by looking out at the room. “People, remember: this is a ballet, not a rodeo.”

And every night it was. It was theater at its highest level. Watching the calculated choreography between the customer, the captain, the sommelier was such a wondrous experience. I now use Michael’s phrase all the time, whenever I feel myself becoming unmoored. It reminds me to stay focused. Be graceful. Know that this is not a brutish sport. This is a dance.

For almost three years, I worked in the line of fire, so to speak, managing special events and projects in-house for Daniel, Café Boulud (New York and Palm Beach), and DB Bistro Moderne. All are temples of haute cuisine, among the most sophisticated and creative restaurants in the country.

Daniel, the East Side flagship, has been named one of the top ten restaurants in the world; it earned four stars in the

New York Times

(the highest rating the paper bestows) and has landed the number one ranking in New York’s famous Zagat survey.

Everything about Daniel is decadent. The main dining room at the time resembled an Italian palazzo filled with thousands of fresh flowers. You entered from a grand foyer on Sixty-fifth Street. To the right was an intimate lounge with lushly upholstered chairs and low tables. Beyond it was a private dining room. Just past the lounge was the restaurant’s bar. Then, past the maître d’ and reservation desk was the entrance to the main dining room.

There were two seating levels. We called them the “pool” and the “balcony.” The ceiling of the foyer, lounge, and bar was made of hand-painted wood in the most luxurious colors: deep rust, cobalt blue, blood red. The velvet furniture matched. The huge floral arrangement at the front of the restaurant was always evocative of the season. It changed every week and always took my breath away. The small bouquets on each table echoed the large one.

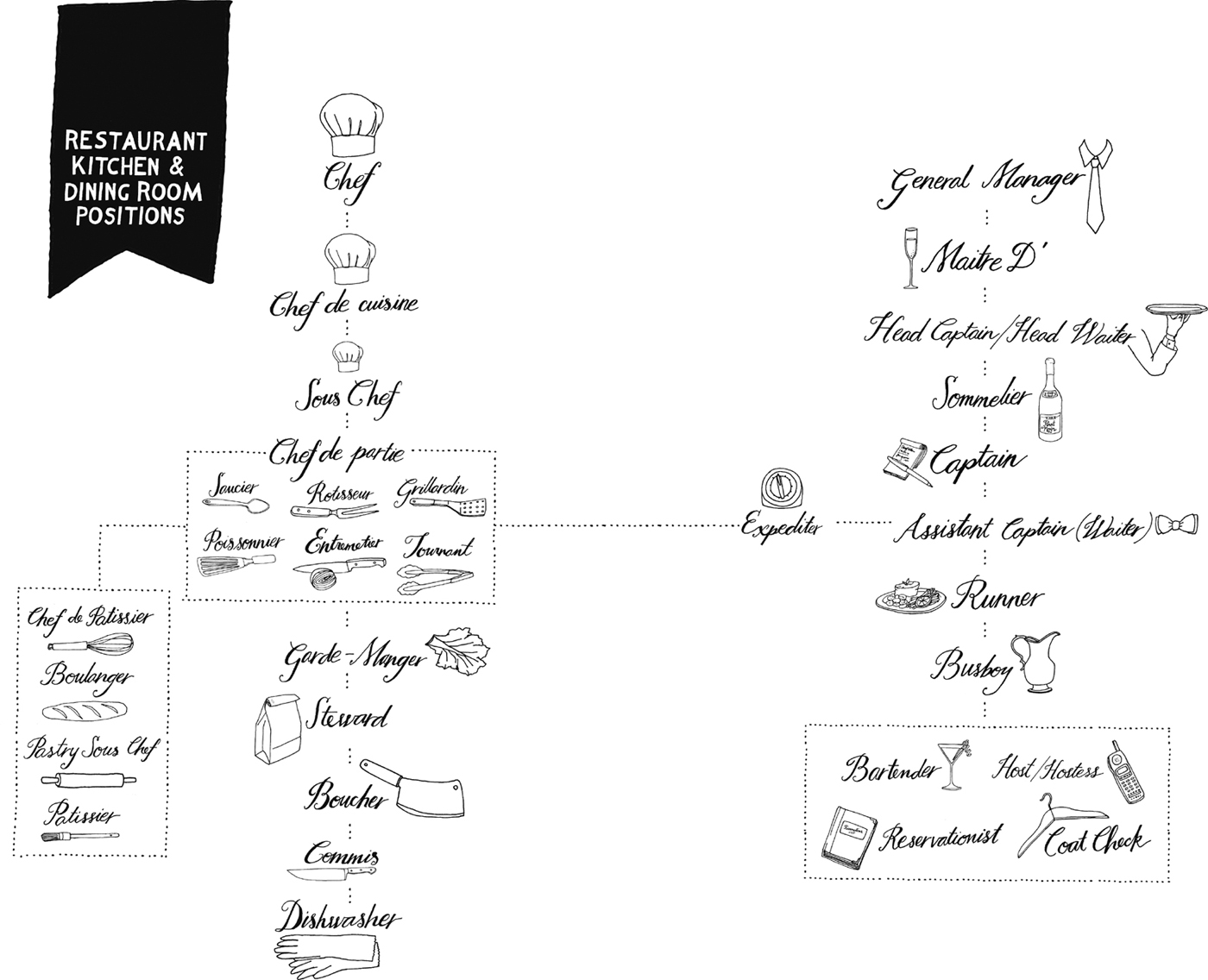

The front-of-house (industry-speak for everyone who works in the dining room with guests, from coat check to general manager) is a brigade the same way the kitchen is. If you’re coming up as part of the front-of-house staff, you start as a busboy, setting and clearing the tables, pouring the water, serving the bread. Then you become a runner. Runners deliver food from the kitchen to the table, keeping in mind the positions of every seat in the room. Assistant captains, also known as waiters, do the actual serving of food and drinks.

Captains take the guests’ orders, as if the positions at each table were numbers on a clock. They make recommendations and oversee all the other service staff in their designated section of the dining room to make sure the meal flows perfectly for their guests. At Daniel, the assistant captains set down the plates at the table and lift off their cloches simultaneously so that everyone’s food is served at the same time and the right temperature. Above the captains are the maître d’s. The head maître d’ handles the reservation service. He makes sure that everyone is seated at the right place and VIPs are treated appropriately, that every occasion is timed correctly and celebrated, and everyone leaves with a smile. When I worked there, the head maître d’ was a charming young Austrian with perfectly styled hair and suit, and a knack for charming even the most jaded of guests in the room.

To ensure perfect timing, an expediter stands at the pass (the counter where the food is picked up that divides the kitchen chaos from the waitstaff ). As soon as you start your third course, the expediter knows to fire the fourth. Guests are at various stages of their meals, so it can be an incredibly complex orchestration.

The waiters at Daniel were real professionals, and I was in awe of them. I had never spent time in the front-of-house before. The kitchen is one thing, I was perfectly comfortable there, but the front-of-house was a different universe altogether. The chefs train and toil. They hone their craft. And the servers do, too. There is often an animosity between the front and back of the house. The front gets the tips, and they have to answer for any mistakes made in the kitchen. The chefs don’t, and they live in fear that the waiters will get something wrong.

The waiters at Daniel made significant salaries. These were no part-time actors. This was a full-time, dedicated job. You had to know and taste everything. The wine list had more than sixteen hundred selections. You had to know the characteristics of each bottle and understand how they all paired with any given dish.

There were also three sommeliers on the floor at all times. The wine cellar was actually two floors below the dining room. We had the skinniest sommeliers in New York, because they had to run up and down two flights of stairs countless times a night.

Everyone at Daniel was hands-on, especially the man himself. Even though it was an international company, it was family-owned and operated. Daniel lived in the apartment over the restaurant. He was there every night and noticed every detail.

The administrative offices, where I worked, lay deep in the recesses of that culinary oasis, through four immense kitchens, just above the twenty-five-thousand-bottle wine cellar. My official job title was special events manager under Georgette, the PR and marketing director for Daniel’s restaurants and projects. Under her guidance, I handled all the events Daniel himself appeared at—for charity, for promotion, and for press. I worked on the marketing of all his restaurants, everything from the design of the Christmas card and business cards to the strategy for his line of knives and cast-iron pots.

There was a lot to keep me busy—three cookbooks already written, with three more on the way; another restaurant opening; and numerous TV, magazine, and charity appearances. My job wasn’t my only challenge. If you think it’s hard not to gain weight on

Top Chef,

you should have seen our workplace.

My goal was not to stay thin—an impossibility. It was basic survival: just trying to get through a day without making a total pig of myself, when the opportunities were endless. Each week presented a new set of obstacles for my willpower, and my stomach, while at the same time introducing me to a new batch of heavenly delights and what I called “educational research adventures.” I actually kept a food diary one random October day in 2003. Here it is:

9:07 a.m.

Arrive at the office; walk through the vast prep kitchens, pastry station, and bakery to my desk. Stocks are simmering, butchers are butchering, and chocolate ganache is swirling in its bowl. I grab a piece of fruit from a walk-in refrigerator larger than my Greenwich Village apartment to start things off on a positive note. Fetch my morning coffee, with milk and sugar, from a half-empty, lukewarm urn tucked in between the ice machine and the vegetable prep area.

10:15 a.m.

The bakers are first to start work each morning, arriving as early as 4 a.m. to begin mixing, proofing, and finally baking the bread for all of Daniel’s New York eateries. A waft of freshly baked goodness floats aimlessly across my desk from their bakery, just steps away . . . walnut raisin loaves, olive rosemary rolls, butter and garlic, hot Parmesan buns. I grab a fresh croissant from the cooling rack and run back to my desk undetected. It’s all downhill from here. . . .

11:34 a.m.

Sandro, the pastry sous-chef, is experimenting with a new batter for citrus meringue cookies—I pass his workstation on my way to a meeting and look at him longingly. He lets me taste it.

12:15 p.m.

“Family Meal” is served. Since the restaurant has close to 150 employees, many of whom work tirelessly in twelve-hour shifts without much time for a break, we are provided with two meals daily (lunch and an early dinner before service begins). Today’s lunch is paella with chicken, olives, and roasted red peppers; heirloom tomato salad with pea shoots and balsamic vinegar. I fill my plate with rice and salad and stand near the main counter of the service kitchen, an immaculate 1,750-square-foot space designed by the chef himself and used for the cooking, garnishing, and plating of all dishes during dinner.

This kitchen accounts for only a small portion of the total back-of-house—a term referring to the behind-the-scenes areas of a restaurant. Besides the kitchen, it includes the locker rooms, the massive wine cellar, storage for everything from printed material to dining room equipment, the administrative offices, and the stewards’ offices. The stewards coordinate all ordering and deliveries in and out of the restaurant. All around me chefs are preparing for dinner: slicing, broiling, peeling, stirring. Chef de cuisine Alex Lee calls me over to where he is standing behind the counter and gently places something in my hand—a thin slice of white truffle from Alba, Italy, the first of the season. I love my job.

3:23 p.m.

My stomach is rumbling again. I take a short break from my computer and wander toward the Chocolate Room, a closetlike space behind our office, kept strictly at 60°F (15°C), which stores our fragile, handmade chocolates and sugar garnishes. Pastry chef Eric Bertoïa is coating a fresh batch of perfect truffles with the restaurant’s insignia stenciled in edible gold leaf. These precious morsels are served as petits fours at the end of the meal—a last bite of sweetness before diners go on their way. He smiles knowingly and hands me two dark chocolate pieces: one filled with banana and one with praline. How can I resist?

4:30 p.m.

The second family meal is served: spaghetti and meatballs with salad. I take a pass reluctantly (unlike most people here, I leave work before midnight and can eat dinner out), but still manage to steal a bite from the general manager’s plate as he dashes off to the waitstaff’s predinner meeting. (The general manager is the top of the front-of-house brigade, the way that the chef de cuisine is the top of the back-of-house brigade.) Every demand is addressed, from birthday celebrations to favorite tables, strategic ring placement for marriage proposals, food allergies, and specific dining tastes—Bill Clinton likes frog’s legs; Woody Allen enjoys the energy around him when he sits in the center of the room; while Whoopi Goldberg prefers to dine at our tented, more private corner tables.

5:12 p.m.

Walking past the dining room to the kitchen, I encounter Pascal, the fromager (our cheese expert, in charge of buying all the cheeses for the restaurant, as well as educating the staff on their rich, subtle differences). He is placing today’s treasures on a rolling cart used for cheese selection during dinner. Guests may choose to include a cheese plate in their meal, between the savory and sweet courses. It is Pascal’s job to always have at the ready a range of cheeses from around the world to present to them, paired with fresh and dried fruits, nuts, honey, or wines. He cuts off the edge of a soft, pungent Livarot from Normandy that we discreetly share. No one can deny that I’m getting an education!

6:52 p.m.

Katherine, the in-house recipe editor, tester, and jill-of-all-trades, is trying out a dish for Daniel’s latest cookbook: Rocky Road ice-cream sandwiches! Not the ones wrapped in waxed paper either—these are thick and gooey, with a brownie on the bottom and a vanilla streusel cookie on top. I dive in, giddy with excitement. Upstairs the kitchen is in full swing and I can hear Chef Daniel making his rounds in the dining room. He’s saying hello to his regular guests, greeting an out-of-town chef who is here for the first time, making sure everyone is blissfully satiated. Downstairs the Rocky Road ice cream is starting to drip from my hands onto the files on my desk.