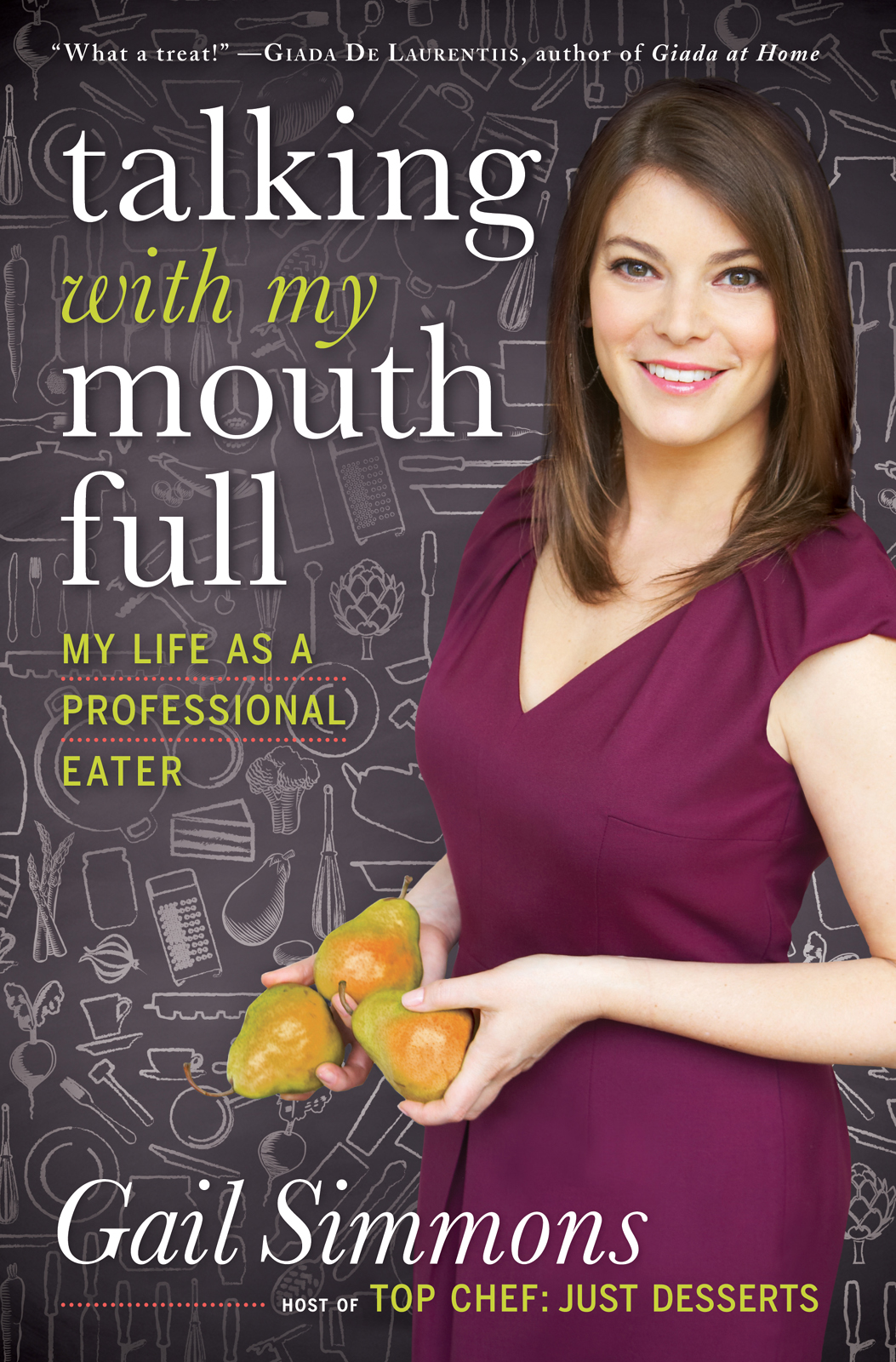

Talking with My Mouth Full

Read Talking with My Mouth Full Online

Authors: Gail Simmons

Dedication

For Jer

Contents

Â

Â

Eat. Write. Travel. Cook.

I love to eat. Not in a gluttonous way. Not in a pack-it-in-as-much-as-you-can-as-fast-as-you-can sort of way. I love the ritual of eating. How the way you hold your knife and fork (or chopsticks or fingers), and what you choose to put between them, determines so much about who you are, where you are from, how you came to be eating this very meal.

I love how everyone in the world has a different palate, different likes and dislikes, nuanced phobias or aversions, obsessions or cravings, which shape the way we nourish ourselves. I love how, like a thumbprint, no two people’s noses and tongues perceive smell and taste the same way. I, for one, have come to realize that I much prefer salty, savory foods in the morning. Runny poached eggs with spicy Sriracha, hearty grain toast and butter, avocado, smoked salmon, bacon.

I am pretty democratic in my love of food and its applications for lunch and dinner. I love vegetables and fruit as much as I love meat. I love fish, seafood, and whole grains. I absolutely love dessert. Not a lot, not every day. But most days certainly, I adore a bite or two of something rich and sweet at the end of the last meal of the day. Or as a midday snack. Ice cream. A simple fruit tart, especially when the fruit caramelizes on the outside but is still a bit juicy within. A chocolate éclair.

I also know I love vinegar and I love chilies: pickles and heat. I love creamy, pungent cheeses. Maple syrup. Fresh corn that you can basically eat raw. Peaches (my favorite white peaches are Opals, and Cal Reds are the juiciest you will ever taste). Spaghetti alla carbonara. I love dark chocolate. So does my father. But I love how it’s possible that one of my two older brothers, raised eating largely the same meals as me for the first two decades of their lives, doesn’t eat vinegar and the other doesn’t eat chocolate.

From an early age, I knew my biggest interest was food, but what could I do with this information? No teacher at school suggested I might be able to make a living as an eater. Back then, our cultural obsession with food wasn’t nearly the juggernaut it is today. Reality TV was just in its infancy when I graduated from college in the late 1990s, so the thought of judging professional chefs on national television would have never entered my mind.

On the eve of adulthood, my friends would declare with confidence: “I’m going to medical school.” “I’m going to law school.” “I’m doing an MBA.” “I’m getting a master’s in art history.” “I’m going to law school.” “I’m going to law school, too!”

Nothing against law school, but how did they know? Was I the only person without a clue about the next step? It sure felt that way. My parents and my friends’ parents expected great things from their children, and great things usually involved postgraduate degrees. Graduate school is great if you know what you want to do. But I didn’t have the foggiest idea. None of the things my friends were doing interested me.

Especially

law school.

I felt at the time like the only one in my crowd—full of so many bright, strong young women—who really didn’t know what she wanted to be. So where did that leave me?

Well, after college, it left me back at home, in my parents’ basement to be exact, where I spent a month or two feeling sorry for myself and depressed. I was lost. I couldn’t believe that not one professor or advisor, in four years of attending one of the best colleges in the country, ever said, “Let’s start planning for when you leave here.” I couldn’t believe I’d never thought about it myself. Then one day at a family dinner, my mother, who was starting to worry, made me sit down with the accomplished daughter of one of her closest friends. She was about ten years my senior. She listened to my dilemma.

Then she handed me a pen and said, “Make a list of what you like to do. Not jobs. Just anything that comes into your mind.”

On a random piece of paper, I wrote: “Eat. Write. Travel. Cook.”

It seemed like a ridiculous exercise. But this wonderful woman (who now works for the Food Network Canada, of all places) smiled.

“See?” she said, pointing at my paper. “You’re not lost. What’s your mom so worried about?”

Like an eerie fortune cookie, that scrap became the trajectory of my life.

What do I do for a living? I eat endlessly as a judge on

Top Chef

, write and talk as a food authority in the media, travel the country and beyond for

Food & Wine

, and regularly cook at events, online, and on television. Without a map, I’ve actually managed to turn my curiosity, enthusiasm, and passion into the life of my dreams. Fifteen years ago, I never could have imagined all that could add up to such a satisfying life.

That’s at least in part because the job didn’t exist yet. How could any of us have known—even as recently as the 1990s—that a love of good food and the people who make it would spawn an industry so much larger and more layered than just chefs and restaurants?

It hit me more than ever the night of

Top Chef

’s Season 3 finale, which we shot at the top of Aspen Mountain. We ate the final dinner from 4:30 to 8:30 p.m. It was August—hot and beautiful, with zero humidity. There was a three-hour break while the crew reset. In the meantime, Bravo’s senior vice president of programming, Andy Cohen, came up and interviewed us for a short video that appeared on the show’s website.

The sun went down and it was soon below freezing at the top of the mountain, ten thousand feet above sea level. We had blankets on our laps under the table. It was absurd how cold it was.

The cameras rolled on Judges’ Table from 11:33 p.m. to 4:06 a.m. But we could still not agree on the season’s winner. Finally our producers sent all but one of the camerapeople home, and for another hour we continued to debate between chefs Hung Huynh and Dale Levitski. They literally forced us to sit in a room together until we all were unanimous in our decision. If there’s even one judge holdout, he or she has to relent and be comfortable with the outcome before we can continue.

We agreed that Dale had higher highs and lower lows. But Hung had been more consistent throughout his meal. Two of Dale’s dishes, scallops with purslane and grapes and lamb with eggplant, tomatoes, and squash, left a substantial impact on us, but his foie gras mousse and his lobster with gnocchi in curry jus were quite flawed. Hung’s were technically precise, beautifully presented, like his pristine shrimp with palm sugar, cucumber salad, and coconut foam, but not always as exciting. They didn’t hit us in the face with flavor the way Dale’s two dishes did.

Our question came down to this: Would you rather have really exciting food that sometimes misses the mark by a mile, or would you rather have a consistently good, well-crafted meal? Tom and I were down for consistency and Padma and Ted Allen were arguing for excitement.

We were freezing and exhausted. In the end, we decided that the sign of a more mature chef was a consistent experience, and picked Hung.

As the sun rose all around us, we knew we had to walk away. It was six in the morning by the time we headed back down the mountain.

As I watched the sunrise from the gondola, I realized my job was about to change the course of two young chefs’ lives.

All because I loved to eat.

My Mother’s Kitchen Counter

MY MOTHER BAKES

plum tarts every year in late August. The smell fills the house. As they bake, the juicy plums sink into the vanilla cake base. I’m smitten by the smell, the vanillaness of it. My mother’s kitchen counter overflows with bowls and vessels. So many that it is often hard to find room to cook. There are ten different kinds of vinegars and oils. A smattering of porcelain teapots. A giant wooden bowl shaped like a carrot, always filled with peanuts in their shells. A little glass cloche containing soft runny cheese. A bowl of dried fruit—pears, apples, prunes, and apricots. A beige ceramic butter dish with soft butter, one of hundreds of ceramic pieces my parents have collected over the years. Clementines in winter. Peaches in summer. Wasabi peas. Spiced pumpkin seeds. Whole walnuts, hazelnuts, and almonds alongside an ornate silver nutcracker. A loaf of zucchini bread with flecks of green.

A magnet on our refrigerator read: “A gourmet is just a glutton with brains.” It served as the family motto.

I grew up in a four-bedroom redbrick house built in 1948, in the picturesque central Toronto neighborhood of Cedarvale. It was a real

neighborhood,

even though it was in the middle of a bustling metropolis, less than a fifteen-minute drive from downtown. It was an upper-middle-class community, with a large Jewish population. The three sizable synagogues within walking distance of my house made parking on any observed holiday a treacherous task. There was a big apple tree in the backyard, perfect for climbing, and a little door under the stairs with a sign that read

PRIVATE: ALAN & ERIC’S HIDEAWAY,

belonging to my older brothers. They let me hide out there, too.

My father, Ivor, is from South Africa, and my mother, Renée, is a Montrealer. They moved to Toronto independently and met and married in 1966. They created an adventurous environment for us in that house. Shelves of books, including every last Hardy Boys novel and fairy-tale anthology, lined the tiny passageway between my and my brothers’ rooms. They would visit me via this passageway to torment or entertain me, depending on the night.

Like so many Canadian kids, my brothers and their friends played hockey in the streets, throwing me in as goalie when they were down a player or two. We rode our bikes to school. We had lemonade stands every summer, with pink juice thawed from frozen concentrate tins, and annual street-long yard sales. On Halloween the neighborhood dressed itself up, with haunted houses and jack-o’-lanterns, cauldrons bubbling over with dry ice on the neighbors’ front lawns, and yards of cotton, subbing in for cobwebs, draping their windowpanes. Not surprisingly, my best costume of all was when I was ten years old and dressed as my favorite Canadian chocolate bar, Mirage. I fashioned it out of a cardboard box painted dark brown and a yellow garbage bag.

Forgive me for assuming you don’t know, but for non-Canadians: Toronto is the economic capital of Canada. The Greater Toronto Area is home to more than 5.5 million people, with influences from all over the globe and one of the world’s greatest Chinatowns outside of, well, China. It is often cited as the safest large metropolitan area in North America. I am always amazed at how few people know that it is the fifth-largest city on the continent, behind only Mexico City, New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago. The CN (Canadian National) Tower, one of the tallest freestanding structures ever built, dominates the skyline. I often tell friends who have never been to Toronto that it is similar to Chicago in feel. It’s also situated on one of the Great Lakes, Lake Ontario, but somehow we screwed up the waterfront by constructing a massive highway that barrels right through it. Americans love to talk about how clean Toronto is, which drives my mother crazy because she feels that it’s no longer true.

And yet, our neighborhood was more or less spotless, and the schools were good. I went to Cedarvale Community School. It was small, with about three hundred children, and hosted a huge annual spring fair that, until late into my teens, was my single favorite day of the year. For me, the most important part of that fair was always the Make Your Own Cupcake booth. Go figure.

I’ve always thought the way my parents got together was very romantic. They married rather late for the time period. My mother was twenty-seven. My father was twenty-nine. My mom’s friends were all married with kids by the time she met my father.

Like me, my mother had two older brothers, Mel and Bernie. Her father was a hardworking and entrepreneurial Polish immigrant who made his fortune in the

schmatta

business (Yiddish for the garment industry). During the Depression and into World War II, he made an impressive living manufacturing inexpensive women’s dresses.

This allowed him to buy an architecturally iconic house on auction in a very exclusive part of Montreal called Westmount. The original owner, Emile Berliner—inventor of the disk record gramophone and early versions of the microphone and the helicopter, among other things—died in 1929.

When they moved in, in 1939, the parks had signs that read

NO JEWS AND NO DOGS.

But here was my mother’s family living in the heart of the neighborhood in a beautiful old home.

For a time, they had a Chinese chef named Chang, who taught my mother how to cook and the rituals of eating Chinese food. My grandmother, an excellent cook herself, used to come home at the end of the day to find my four-year-old mother sitting cross-legged on the counter of the kitchen, bowl up to her chin, expertly shoveling rice into her mouth or slurping noodles with chopsticks. Chang also introduced my mother to steamed pork buns, or char siu bao, which somehow became one of my many childhood nicknames, often shortened to Char Siu or “Chash.”

My mother’s parents were unhappy together for the better part of thirty years and finally divorced when my mother was in her last year of college; she moved into the residence hall at McGill University to get away from all the drama. She had entered college at the age of sixteen, and when she graduated at twenty she pursued a master’s degree in European politics at the Collège d’Europe in Bruges, Belgium. Then she traveled through Europe and Israel, meeting up with people along the way, one of whom was Leonard Cohen, my uncle Bernie’s oldest childhood friend. She says they weren’t romantically involved, but I’m suspicious. Because, come on, how can you travel abroad with Leonard Cohen and not be enchanted by him?

She stayed in Israel for a brief period, then moved to New York and got a job as a guide at the United Nations, where she had to walk dozens of miles a day giving tours to visitors—in heels. The guides were from dozens of countries and spoke countless languages. By sheer coincidence, one of the other guides at the time was none other than Madhur Jaffrey, now the best-known Indian food authority in the West. She’s written the most influential Indian cookbooks in English and since those days has become a notable actor both in India and here.

After less than two years, my mom, in her mid-twenties and still single, moved to Toronto to be near her brother Bernie and her best friend, Linda. She got a job in public relations for the Toronto Symphony and took her work very seriously. At the time Linda was trying to have a baby.

“I bet I can have a baby before you find a husband,” Linda dared my mother.

“No way,” my mother said. “One hundred bucks on the table.”

Well, as luck would have it, just a few months later Linda was pregnant.

“Now I have less than nine months to find a husband,” my mother thought.

My father was a South African chemical engineer who studied at the University of Cape Town and three years after graduation saved up just enough for a boat to England, arriving there not knowing a soul. Before he left he got a business degree through the University of South Africa and a job in London designing petroleum refineries, which transferred him to Toronto after just over a year.

Two years after moving to Canada, my father, who was now in market research at Falconbridge Limited, a natural resource and mining company, attended a conference of the American Management Association in Chicago. There he met a man from Cleveland who used to live in Toronto and knew my uncle Bernie.

“You’re single and Jewish in Toronto?” he said, getting right down to business. “I know someone whose sister is also single and Jewish in Toronto. We should set you up.”

My father called my mother in the middle of the workday to ask her out. When she answered the phone, the first thing he said was, “Am I interrupting you? Is this a bad time?”

My mother stared back at the phone in shock. This was the spring of 1966, and no man had ever thought to ask her that question before. It was destiny.

Linda was by now almost nine months pregnant. The pressure was on.

Charmed by my father’s discretion and foreign accent, my mother made a date with him for dinner the following week. While he was on his way to pick her up, Linda went into labor. She called my mother to ask, “Can you pick my parents up at the airport? They’re flying in from Montreal. Now.”

My mother didn’t cancel the date. When he arrived at her door, she said, “We can’t go out to dinner, but will you come with me to the airport?” They picked up Linda’s parents and took them to the hospital. And that was my parents’ first date.

Linda’s son Michael was born that night. He’s exactly six months older than my parents’ marriage. They wed in December of that same year. The bet was a wash.

Once married, my parents had some trouble conceiving. This was well before there was advanced fertility technology. Adoption was much easier, so they adopted my two older brothers, two wonderful baby boys, sixteen months apart.

Five years later, my mother was not feeling well, so she went to her doctor thinking she was coming down with the flu.

The doctor did some tests and reported, “Actually, you’re pregnant.”

My parents, the newlyweds

My mother was beside herself. The next several months were a bit of a circus. My father called my mom “a moving target.” She had just managed to get both her boys off to school and was preparing to get back into the workforce full-time, to be her own person once again. And then I came along—a miracle or a mistake, depending on whom you ask.

She had only one pregnancy craving: she would wake up in the middle of the night demanding chocolate éclairs. I feel like that explains a lot.

The story goes that my parents, feeling blessed to have a healthy baby daughter after having two sons, named me Abigail, meaning: “the father rejoices.” My brothers and I joke that we are all firstborns and we are all mistakes. But we found ourselves, through luck and the mysterious power of the universe, in a family where we were all much loved.

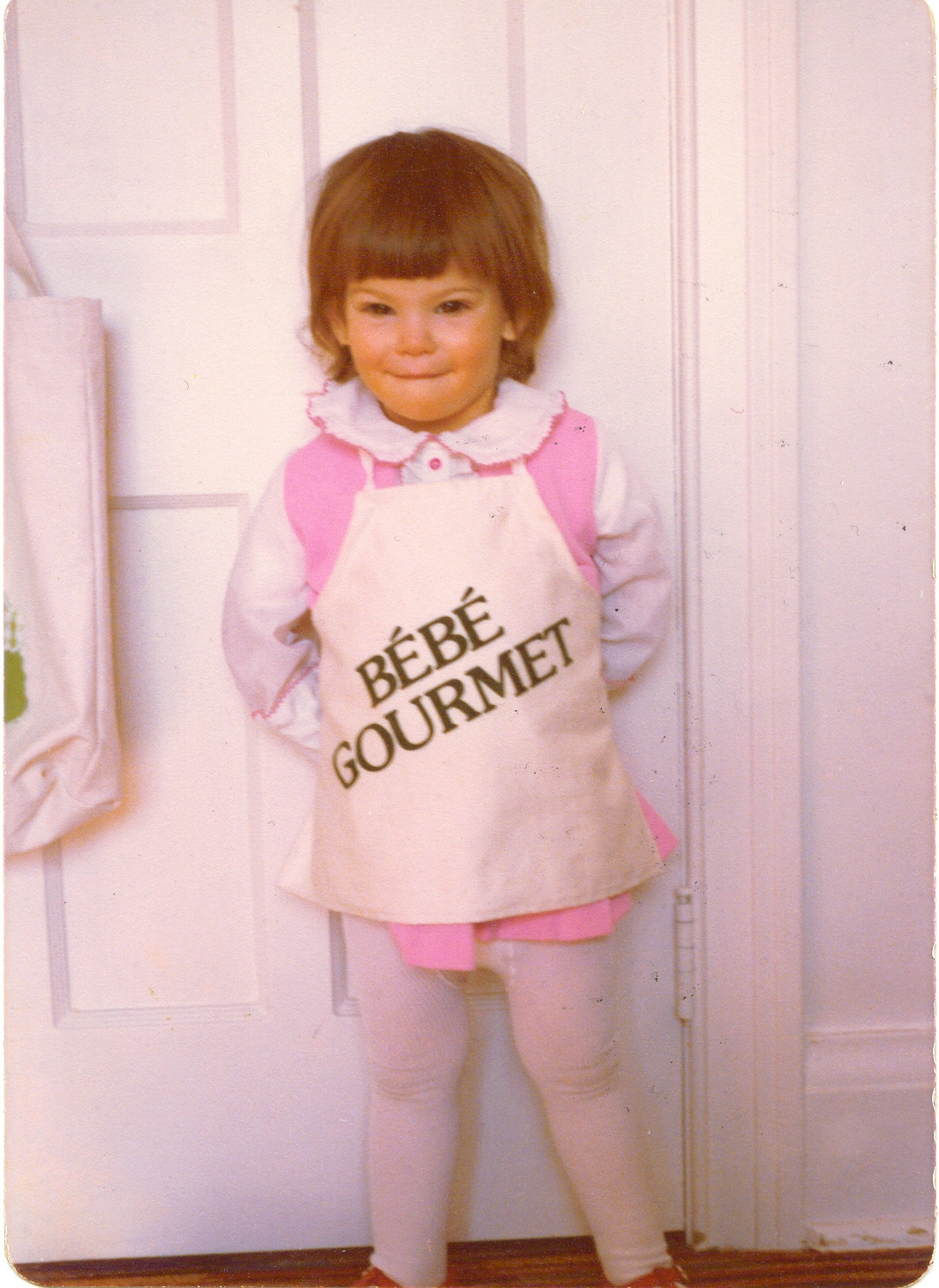

My mother had a lot of nicknames for us, because a nursery school teacher once told her: “A child who is loved has many names.” Besides Char Siu Bao, my family and close friends have always called me Snip, short for The Snippet. There was a picture taken of me when I was about two years old, on my stomach and elbows in the grass, with my hair in pigtails. The grass is almost higher than I am, and my father once said I looked like a little snippet of grass. It stuck.

To say I came from a food-loving family is an understatement—both my parents, despite their very different backgrounds, grew up loving food.

My mother was a bombshell when she was younger, with jet-black hair, porcelain skin, and serious cleavage (I may have inherited that last trait from her). To this day, she has the most amazing, insurance-worthy Tina Turner legs. I feel good about my legs, but my mother’s legs, even now in her seventies, are ridiculous.

The Snippet

Our personalities are pretty similar. She’s opinionated—sitting across from her at dinner, be prepared to hear in detail her views on the decline of the Paris bistro—and amazingly trustworthy. She’s also tough. Growing up we could not get away with anything around her. We really did not want to cross her. She played bad cop and enforced the law, but at the heart of it all, she was a nurturer.

Everyone I knew went to my mother for advice. Our house was a safe haven for everyone in the neighborhood, especially my friends who struggled with their own family issues. She made them all feel comfortable and welcome. And she cooked: poached Arctic char with lemon and herbs, swiss chard, butternut squash soup.