Talking with My Mouth Full (2 page)

Read Talking with My Mouth Full Online

Authors: Gail Simmons

Her kitchen was full of food. Not fussy or orchestrated, just come-as-you-are. That’s where we would all hang out. She was loud, casual, and always throwing things together.

We were not a religious family, but my parents cultivated a traditional Jewish home, celebrating the major holidays and observing rites of passage through the years the way their parents had before them, with way too much food and a little prayer. We went to synagogue a few times a year. My brothers and I were bar and bat mitzvahed. I went to Hebrew school three days a week from kindergarten through seventh grade.

Although we ate dinner together around the table almost every night, Shabbat dinner was special, no matter what else we had to do. Every Friday, we said blessings, caught up on our week, and welcomed guests to our family table. I always felt the emphasis wasn’t so much on religion as on deeply rooted tradition: family, food, and relaying the oral history of our people.

My mother still likes to say her kids were weaned on leek quiche and pâté. My mother has a thing for pâté. It’s always in her house. As children I don’t think we liked it much. I can never remember asking for it. My mother made a mean chopped liver, but I wouldn’t call it pâté. It was more of a coarse Jewish chopped chicken liver, pureed with onion and seasonings. She kept it in the refrigerator in a green ceramic pot with a lid.

But I can’t figure out what it is with my mother and French forced meat. When she would come to visit me in New York, before I was married and was living alone in my first apartment, she loved to take me grocery shopping, as mothers do. Sometimes she still goes shopping with me, and she can’t help herself: without fail she buys me pâté—duck, pork, or even veggie versions. Pâté is not something I typically keep in my house. Sure, I like it just fine when it’s served to me at a restaurant, but I can’t think of a time I’ve ever served pâté at home. I tell my mother this time and again, but to no avail. There it is in my fridge. I think in her head she sees it as an emblem of luxury. Maybe she thinks it’s something she’s treating me to. It’s a mental block. She’s in denial.

But I shouldn’t complain. We grew up in a plentiful, healthy eating environment. We ate around the table together every night at six thirty, after my father came home from work, and my mother would call us all downstairs in her booming voice, “ALAN, ERIC, GAIL! SUPPER!” Eating together was an absolute.

There was one exception: my first birthday. For the first few weeks after I was born, my parents had a baby nurse, Heather. She returned from time to time as we grew, to stay with us when our parents were on vacation. We loved it when she visited, because of the food she made and allowed us to eat: milkshakes, chocolate cake with vanilla and chocolate crisscross icing.

My parents’ first major vacation after I was born was a trip to Paris that coincided with my first birthday. It’s hard to imagine any of my friends in this day and age leaving their kid on such a momentous occasion, but as my mother’s birthday actually falls the day after mine, I guess it was her birthday, too, and they were desperate for a getaway. Pictures reveal that I did not seem to mind much. Heather made one of her famous chocolate cakes and I devoured it happily with my brothers.

With my brothers, and cake, on my first birthday

If my mother was the voice in the family, my father was the strong, silent type. I liken his looks to a cross between Clint Eastwood and Roger Moore. But his personality is more like my hero, Captain Jean-Luc Picard (Shakespearean actor Patrick Stewart to anyone over sixty and Professor Charles X of

X-Men

to anyone under thirty), serious and stoic.

When I was a little girl, people told me all the time how I looked just like my father. I would cry and run out of the room. I thought they were saying I looked like a boy—an adult boy at that! Now I realize how much my facial features really do mimic his—my eyes, the shape of my face, the dimples on my cheeks when I smile.

Inquisitive and soft-spoken, he’s played the recorder for more than forty years, and played the flute for many years before that. He still takes lessons once a week. He’s an avid environmentalist and sails often in the summer. He reads a book a week, sometimes more, enjoys bird-watching, scrapbooking, and long walks in nature. If he were single, he could write one hell of a personal ad!

My father rarely raises his voice. When we were growing up, it took a lot to make him angry, but when he was, you did not want to be around for it. There are only a few times I can remember when he was truly furious.

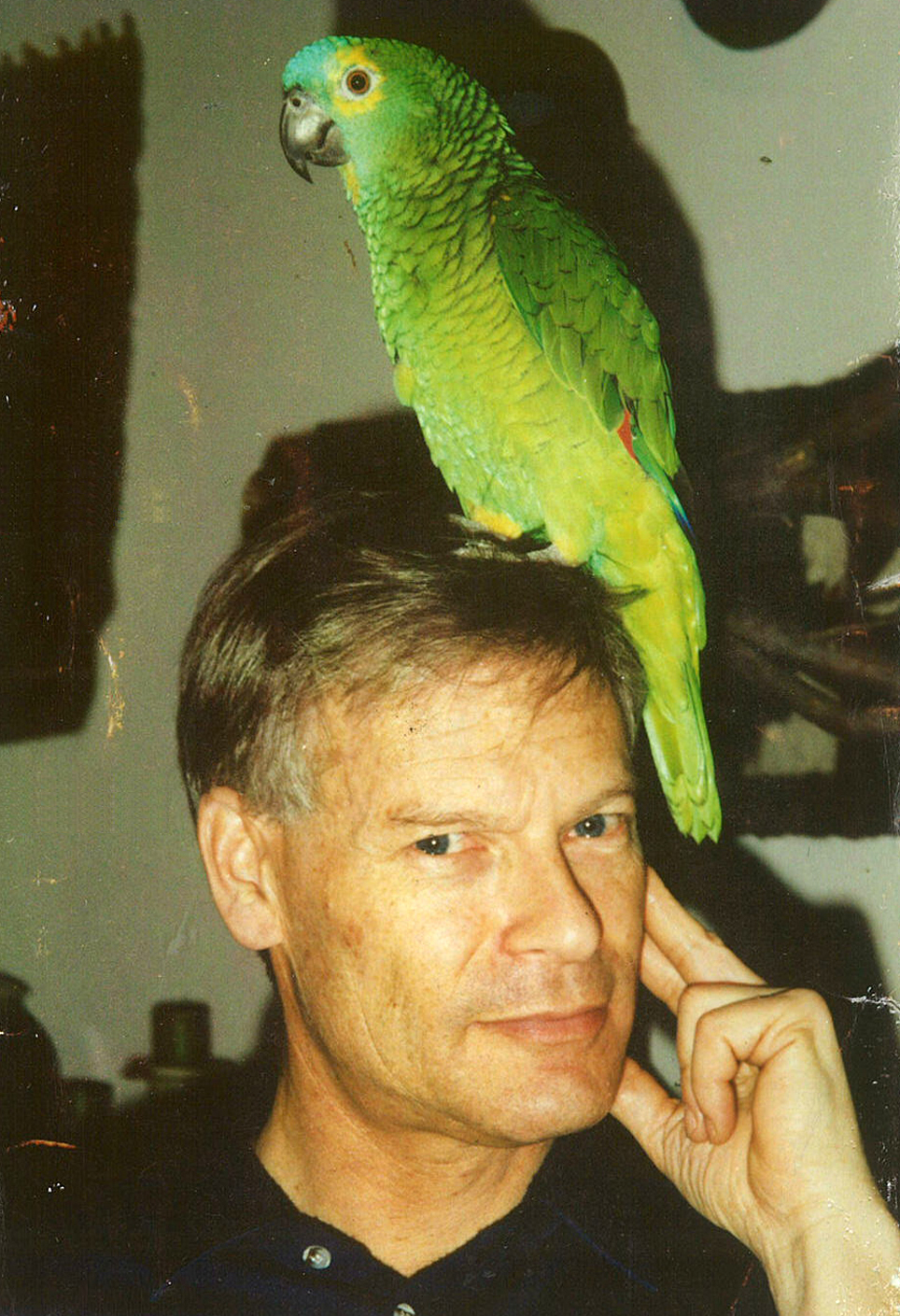

Perhaps most important in describing my father is that he has a parrot named Toby, with whom he has an insanely intense relationship. He (or she; we have no way of knowing Toby’s gender without performing surgery) is about twenty-two years old. But parrots can live past sixty, even in captivity. Suffice it to say, Toby’s in the will. In the absence of a mate, parrots bond with their caregiver. For life. So my father is the closest thing Toby has to a spouse. It’s not completely healthy. I justify it as my father’s answer to empty-nest syndrome.

My mother doesn’t like Toby much. Neither do my brothers and I. My dad calls it sibling rivalry. I call it downright crazy. Toby tolerates my mother because she feeds him, but he attacks most other people who come near my father. On one occasion, years ago, Toby bit right through my poor uncle Lou’s ear. Blood was spilled. A dog could have been put down for such an outburst. Dad, of course, just giggled and checked to make sure Toby was not hurt in the ordeal.

My father still resents the fact that my brother insists Toby has to stay in a cage when my nieces and nephew visit.

“Toby was here first!” is his response when he’s asked to put Toby away.

“No, Ivor,

I

was here first” is my mother’s rebuttal. Who can argue?

My mother has her own plans for Toby. “I’m teaching him to lie down in a skillet and say, ‘coq au vin.’ ”

My dad is certainly passionate about food, but being from another generation, he never learned how to cook. And because my mother was so adept in the kitchen, he soon grew spoiled. Not only was my mom genuinely talented, but also his standards started out pretty low, as his own mother was a terrible cook. She was an incredible woman, a piano teacher and a gifted knitter. I didn’t see her or my grandfather much, since they lived in South Africa, and she died when I was twenty-two. In the course of those twenty-two years I only spent about a dozen visits with her.

Dad and Toby

I’ll give my grandma the benefit of the doubt and say perhaps she just didn’t care much for food and cooking, as what came out of her kitchen was predictably horrid. I hadn’t actually experienced what my mom and dad meant by this firsthand until I was thirteen. My grandparents were getting older and couldn’t make the trip to Canada anymore. It was the year of my bat mitzvah, so my father and I went to visit them in South Africa as part of the milestone birthday present. Sadly, it turned out to be the last time I would see my grandfather. He died just a few years later.

They were still living in Bloemfontein, the town where my father had grown up. It’s located in the center of the country and is its judicial center and the capital of the Orange Free State—a landlocked town, not far from South Africa’s legendary diamond mines. At the time my father grew up, it was a heavily Afrikaans-influenced place, even though my father’s family was English-speaking.

On this particular visit, my grandmother made dinner for us. My Jewish guilt compels me to say up front that I love my grandmother dearly and cherish her memory. But, according to my mother, my grandmother would put a chicken in the oven at nine in the morning, go out for the day, and then take it out of the oven at six at night. I had thought she was joking, but she was exactly right. It was the most amazingly dry roast chicken I can remember. So tough that it stuck in my throat. There was no water on the table, and I had just eaten this giant piece of chicken that was impossible to swallow. I worried about choking. It felt like each bite was never going to end. Luckily, that was the only meal of hers I had to endure. On other visits, we ate elsewhere.

When my mother and father first met, she used to make him all sorts of elaborate meals and take him out to Indian and Italian, Chinese and French restaurants. She thought his mother had been an exemplary cook because he had such a sophisticated palate and such enthusiasm for good food. My father told her that, on the contrary, his mother’s cooking had barely kept him alive.

As a result, my father would do the dishes and the sewing in the house, but rarely the cooking. That said: my father did make four things when I was growing up that I remember fondly.

Dad’s homemade wine label

First of all, he made wine in our basement. Some of it was even pretty good. Lately he’s less into wine and more into beer, seeking out microbreweries wherever he goes, but from the time my parents met and into my childhood, he loved wine and made it himself. My mother even had wine labels printed for him as a gift:

CHATEAU SAINT IVOR, PRODUCE DE TORONTO, GRAND VIN DE SIÈCLE, APPELLATION CONTROLÉE.

The three foodstuffs my father made consistently when we were growing up bore no relation to one another. They were pickles, applesauce, and chocolate Cream of Wheat.

My dad’s full sour pickles are amazing and I now have the recipe. He made them every summer, from a bushel of Kirby cucumbers. He would store them in our cellar all year long. They were made with tons of garlic and dill weed, pickling spices, and salt. They’d sit fermenting for months and are still one of my most favorite snacks.

(Full disclosure: I will eat any kind of pickle I can get my hands on, but it’s rare that I can find a pickle as good as my father’s. I love how sour they are. He lets them sit so long that they aren’t bright and crunchy anymore. Totally fermented. I love pickles in New York, Jewish pickles like Gus’s, but I find them a touch salty and not quite sour enough. I love Second Avenue Deli pickles, too, but even their full sours are not quite as good as the Ivor Simmons specials.)

Then there’s his applesauce, which he made once a year, in the fall, the recipe for which I published in

Food & Wine

magazine a few years ago. I would come into the kitchen and see a big basket of apples. My father would be at the stove stirring and pureeing the applesauce, which he stored in our extra big freezer in the basement. There’s usually still applesauce in that freezer when I come home to visit, and I often smuggle a jar or two back with me to New York.

His applesauce is unlike any other I’ve had. It’s pureed until it’s silky smooth, and he adds the skin of Italian prune plums, so it takes on this beautiful deep pink color as it cooks.

We ate his applesauce with everything. On Hanukkah we had it with my mother’s famous dill latkes. Sometimes we would drizzle heavy cream into a bowl of it for dessert, or even for breakfast. It was decadent—sweet, tart, and super-smooth all at the same time.

The chocolate Cream of Wheat was something he’d make for my brothers and me on weekend mornings to give my mother a break in the kitchen. Cream of Wheat is the wheat equivalent of what’s traditionally called

mieliepap

in South Africa, grits or polenta here, made from cornmeal. My father grew up eating

mieliepap

for breakfast, adding milk or fruit to it. Instant Cream of Wheat became the easiest for him to make us, and he would add cocoa powder to it as a treat—never too much, never too sweet. It was special-occasion food, thick and chocolaty, and something I’ll always associate with him.