Talking with My Mouth Full (3 page)

Read Talking with My Mouth Full Online

Authors: Gail Simmons

One of my father’s most endearing traits is that he is a certified chocoholic. I say this in all seriousness. He has an addiction. When we were young, he would hoard chocolate, hiding the stuff around the house so his children would not find it. He kept most of it in his dresser drawer, hidden beneath a sea of navy dress socks. We always knew we could sneak chocolate from there when he went out. I would be surprised if he did not still keep it there in case of emergency. He especially loves dark chocolate, the darker the better: 70 percent and up. I have the exact same taste. Milk chocolate is not true chocolate as far as we are concerned. Dark chocolate is so much more pure and nuanced. You can taste the cocoa, the tannins, and the terroir. (Although I can assure you, my father and I never actually use the word “terroir” when we discuss our love for chocolate. We just like the bitter earthiness.)

He’s a fit man and very disciplined. At around five feet, eight inches, he weighs, at most, 150 pounds. He’s in amazing shape, always has been, and is incredibly regimented in what he eats. My father simply has more willpower than anyone I have ever met.

He eats the same thing every single morning to this day: hot cereal (a mixture of oats, bran, and flax) and two glasses of room-temperature water. He even brings the special hot cereal mixture with him when he travels. He sets everything out the night before.

My mother made his lunch every day of his working life. Although he was trained as a chemical engineer, for more than twenty-five years he had a trucking company that safely disposed of toxic and liquid waste. His office was in an industrial part of town where he could not get decent lunches, so my mother, who was already packing school lunches for us, would pack his as well. As far back as I can remember, my father’s lunch consisted of a sandwich of some kind, two pieces of fruit, and again, two glasses of water.

Then he’d have dinner with us, whatever my mother made, and end his day with two pieces of dark chocolate. He only allowed himself two pieces; otherwise, there would be no limit to how much he could consume. He loves hot chocolate, too, even in the summertime. He travels the world always on the lookout for hot chocolate. He makes himself a cup every single day, and whenever I am home he offers to make some for me, too.

A few years ago, my father had some routine blood work done. His doctor told him his glucose levels were a bit high, that he could be pre-diabetic, and that he couldn’t have chocolate or sweets for a year. My heart broke for him. This put him into a serious depression. Thank God he was told he could still have hot chocolate as long as it didn’t have too much sugar in it.

With my cup of hot chocolate I would sometimes grab a cookie from the cookie jar on our counter. My parents actually collect ceramics and have some wonderful pottery in their house, including this jar.

My mother keeps it on the counter to this day, as a symbol of plenty, a testimony to her bountiful kitchen. Once in a while my father will ask, “Why do we have this cookie jar? It’s just the two of us. These cookies have been in here for a year and a half. Our children aren’t here to eat them, and our grandchildren don’t eat them either. We should get rid of the cookie jar.”

But my mother isn’t listening. It’s like the pâté she’s always buying me. Despite our protests, the cookie jar remains.

Air-Dried Meat in the Glove Compartment

WE’RE ON SOUTH

Africa’s Garden Route, the popular coastal road, somewhere between Plettenberg Bay and Tsitsikamma National Park. An ostrich runs alongside the car. Klipspringer antelopes sun themselves by the side of the road. The landscape is lush and wet. It’s September, the beginning of African spring. We drive down a steep hill and enter a fog so thick that we can’t see more than five feet in front of us. We’re lost in a cloud hovering above the road. My father slows down the car in case there’s another in front of us—or worse, a stray baboon. We are silent, completely focused on the road. I reach into the glove compartment for a little comfort. I pull out a brown paper bag. Concealed inside is our last half pound of my favorite snack. Additional panic sets in as I realize this has to last us the rest of our trip. Sure, there’s biltong to be found at other roadside stalls, but this kind, from Joubert and Monty’s, is the gold standard of air-dried meat. I rip off a hunk and gnaw on it quietly as my father keeps his eyes on the road. We climb up a hill. Instantly, we emerge from the fog. The sun is shining. We breathe a joint sigh of relief and drive on.

Our house was always full of noise and life. We had a TV, but my parents only watched the news and

Masterpiece Theatre.

My parents never cared much for pop culture. Fad diets,

Three’s Company

, and Michael Jackson were not things they concerned themselves with. It was always up to us kids to discover for ourselves anything current besides world news. My father has only ever listened to baroque music and my mother only to classical (if slightly more modern than the 1400s) and classic jazz.

My father hated how much we children wanted to watch television. He couldn’t get us out from in front of it, so he made a rule: no television on weeknights. This drove us crazy. We complained constantly about how all our friends could watch whatever they wanted. To us it seemed sadistic of him to deny us what we, as teenagers, felt was our God-given right.

But it worked. We learned to ignore the fact that we were not in the loop on the latest shows or clothes or toys. We learned to play games or go outside instead. And we read.

I took drama classes and did quite a bit of acting in school, in plays like

Noises Off

and

Blithe Spirit

and musicals like

West Side Story, Sweet Charity

, and

Little Shop of Horrors.

Every summer from the age of ten I went to sleepaway camp, where we produced and performed large-scale productions of

Damn Yankees

,

A Chorus Line

, and

Hair.

We did an especially elaborate and memorable production of

Cats

, which I directed and choreographed, and which starred forty or so thirteen- and fourteen-year-olds.

I took dance classes, too: jazz, modern, tap, and ballet. I danced at recitals through much of my adolescence, but toward the end of high school the inevitable happened—my boobs grew. Not acceptable for a ballerina. This marked the end of that career path.

My parents were constantly throwing dinner parties. Both my parents chose to make their life away from their respective families. So they created their own family out of their friends in Toronto. Our house was full of interesting people, like my father’s first friend in the country, Louis, who is a jazz music fanatic and loves to scat. They remain the best of friends to this day. Uncle Lou’s wife, Sue, had a chain of bakeries when we were growing up, and besides my father and his chronic chocolate habit, she is undoubtedly the person most responsible for my love of desserts. Sweet Sue’s was the name of her bakery chain and she truly is.

My parents’ friends were our aunts and uncles, and their children were our cousins. There was no blood between us, but they were family all the same. They helped raise and nurture us in so many ways. Even my girlfriends still know them as Auntie Sandy, Aunt Sue, Auntie Marilyn, Aunt Rho, and Auntie Linda.

My mother was fiercely independent. Probably because of her parents’ divorce, which put my grandmother under immense emotional and financial stress in her later years, my mother felt strongly that she had to be her own woman. She never wanted to be defined by a man, or by anyone at all. Throughout her life, she had several dynamic careers, first as a publicist, then as a food writer and cooking teacher, and later as a manager of classical musicians.

At the same time she found a way to work from home when we were young. She made sure we were staying out of trouble and, of course, eating well. It’s incredible to me that even though she had a busy career, my mother managed to cook an ambitious dinner for us every night. It was a smart thing for her and a great luxury for us.

My mother redesigned and renovated her kitchen in 1982 so she could teach out of it. Here, she held weekly cooking classes for ten to fifteen people. Most of her students were local women, mothers and friends from the neighborhood, who heard about her by word of mouth. She taught kitchen basics, like how to roast a chicken and make soup stock. She offered classes with themes like making the most of offal (sweetbreads, tongue, chicken livers), improvising in the kitchen based on what’s in your fridge, winter or summer menus, or the best recipes for brunch.

One year, I even remember her teaching a cooking class for husbands, which felt revolutionary at the time. It culminated in a big dinner that they cooked together. My father even dressed up as a French maid to serve the food—he will probably never live it down!

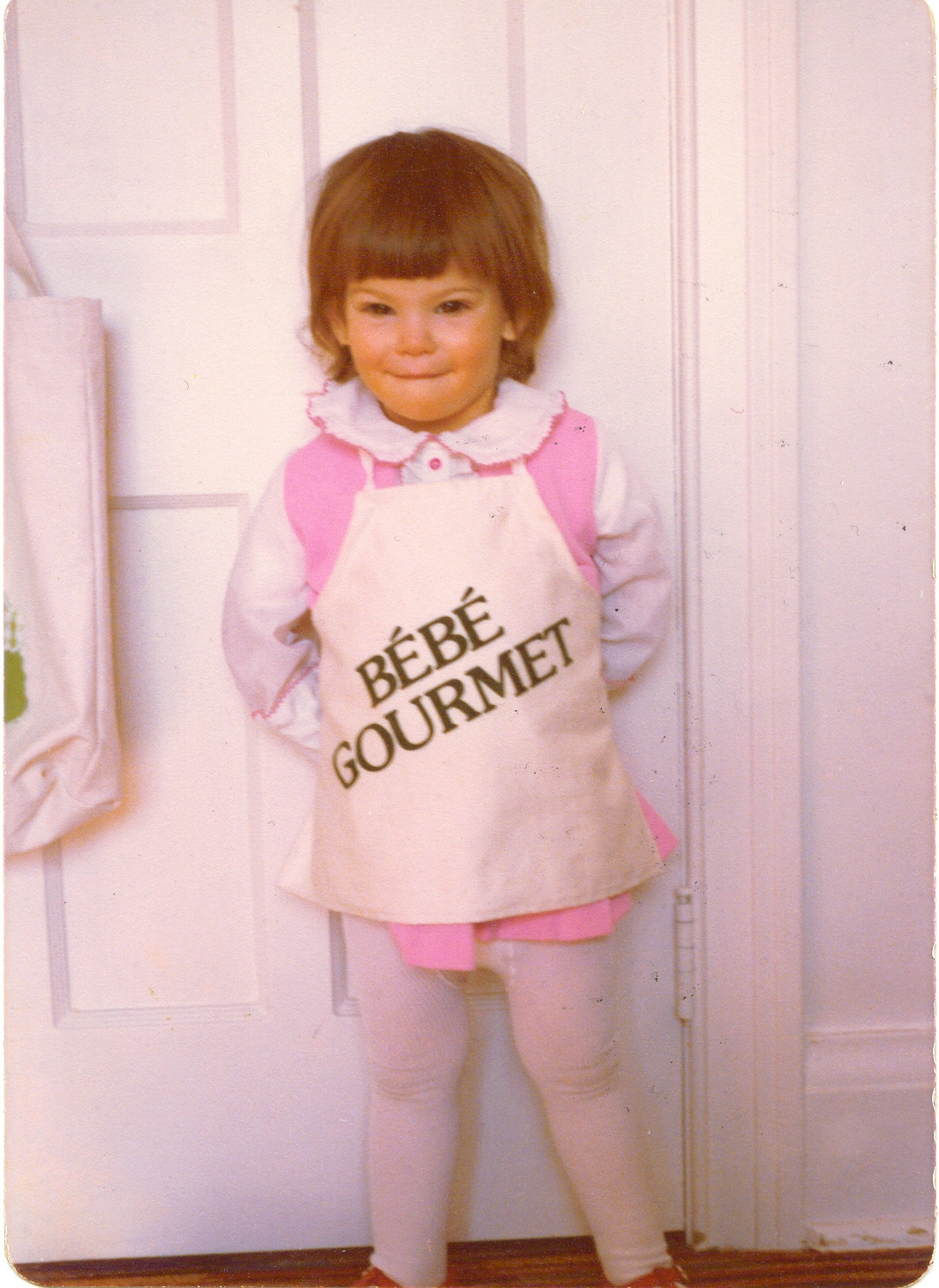

Mom at her crowded kitchen counter, with me as her little helper

For all of us, that kitchen was the place to be. When my parents entertain, everyone migrates there. It’s a warm, bustling place, full of action and excitement. It has always been the center of our home.

Thirty years later, the kitchen could use another renovation, but it’s still very much my mother’s domain. When I’m visiting, I don’t cook in it much. Her kitchen is her territory and I risk her wrath if I mess with it.

I do try to help my mom with family dinners, especially holiday meals, but it’s not easy. She tries to control everything I do. She hovers, hands me Herbes de Provence that have been in her cupboard since 1972, that I don’t want to use, and sticks her fingers in my vinaigrette. I get that it’s her space, but we have different styles. I have professional training, while my mother has instinctive flair. I haven’t had her years of practice cooking for a large family.

Mom’s cooking class final dinner with Dad serving in drag

I admit that I also drive her crazy doing things my way and giving her tips or suggestions that she doesn’t want to hear, like how to hold her knife properly, or that her olive oil is past its prime. She’ll put me in charge of roasting the vegetables for dinner, and I won’t do it until the last second. I can see the steam coming out of her ears because she wants me to be more organized.

Somehow, even though I have a culinary degree and have made my career in the food world, I haven’t actually cooked that often for my family. My brothers joke, “You’re a famous food personality in New York, but you’ve never actually made us a meal.”

My mother always pushed us to be more adventurous. When I was a little girl, she let me run around in her kitchen. I loved to raid her pantry and her dried spice and herb drawer. I would take out a hundred different ingredients to make soup—ketchup, dried oregano, pink peppercorns, Worcestershire sauce, whole-grain mustard, brown sugar, paprika, tomato paste, powdered garlic, fennel seeds, salt—fill a soup pot with water, and stand next to her on my wooden stool that had a grape scratch-and-sniff sticker on it.

I would stir, sprinkle, and season just like my mother. It was kind of disgusting. But the actions seemed so grown-up and I loved the feeling of cooking. Even if the dish was inedible, I felt the thrill of creating.

When I was six years old, my mother let me make scrambled eggs. I wasn’t tall enough to reach the stove, so I stood on that wooden stool; it was about a foot and a half high so I could see into the pot properly. To make it safer, my mother set up a double boiler—a bain-marie. Ours was made of a set of enamel pots, orange on the outside, cream-colored within.

I seasoned the eggs with a cinnamon-sugar mix and raisins. It seemed right at the time. Then I forced my parents to eat them. I realized at that moment that eggs were so much more complex than their simple form let on—a revelation I maintain to this very day. I had turned them from an inedible viscous fluid into a solid yellow food. I was making magic.

In addition to running her cooking school, my mother wrote about food for the

Globe & Mail

. Through her work, she befriended a man named Garfield who owned one of the great restaurants in Toronto’s Chinatown, called Sai Woo. She would often drop by before dinner service started or at the end of the night, when all the cooks and servers would be eating together. My mother noticed they would eat totally different food from what was on the menu. The smells and sight of it would make her drool with envy.

“Why is it that you serve one menu to us,” my mother would prod Garfield, “and you guys eat differently?”

“You don’t want that food,” he would say. “It’s not for you.”

Finally she convinced him to make her their more authentic dishes. And from then on whenever we went, we got only the good stuff: Singapore chow fun, crackling whole Peking duck, Chinese broccoli, and bok choy in oyster sauce. I remember dark, chewy mushrooms, seafood soup, and deep-fried bean curd. Delicious.

The main reason I adored going was that when I left, they always gave me a little box of rice candies. They didn’t really have much flavor. They were just gluten-y and sweet. Each candy was first wrapped in wax paper, which you took off, and then another layer of what looked like cellophane but which was actually edible rice paper. You could just pop one into your mouth and the paper would dissolve instantly. I thought it was the most fantastic candy ever. I would eat the entire box on the way home in the car.

Early on in my career, when family friends learned that I was pursuing work in the food world, they would enthuse, “You’re just like your mother!”

It had never occurred to me that I was following in her footsteps. It made me furious, as if destiny was beyond my control. Not to mention: What twenty-two-year-old wants to be told she’s just like her mother?

Looking back, I now realize it was the greatest compliment I could have been given. My parents raised us to try all sorts of new things, whether it was in tasting exotic foods, traveling to far-flung locations, reading books about the greater world, or forging our own, independent paths through life.

My mother instilled in me a love of her kitchen and an appreciation of home, but also the courage to leave it. She made it clear that food opens up the world to you. Food can be comforting, but it can also take you far outside your comfort zone. She taught me that a woman in the kitchen isn’t a symbol of domesticity, but of empowerment.

My brothers were always getting into some kind of trouble together. They were best friends and constant playmates growing up, though they grew to be very different people.

Alan, my elder brother, is a musician and was a huge musical influence on me. He can pick up any instrument and seduce it, from the guitar, piano, or harmonica to the bugle. He introduced me to the Beatles’

White Album

, to Led Zeppelin and their obscure

Lord of the Rings

references, and to Traffic’s

John Barleycorn Must Die

. Alan was never in the popular crowd. He was an artist, rebellious and independent and always a bit alternative. He was into drama and theater, but didn’t do well academically, either because he couldn’t focus or because he didn’t care. My parents pulled him out of public school after eleventh grade and put him in a small private school, where, finally, he thrived.