Ted & Me (11 page)

Authors: Dan Gutman

If You're Gonna Do Something, Do It Right

F

ISHING

?

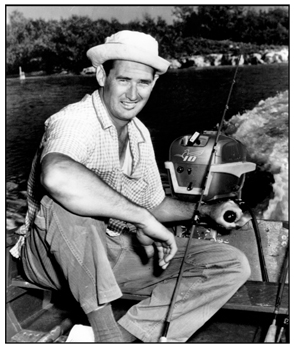

If there was one thing that Ted Williams liked as much as he liked baseball, I found out, it was fishing.

“A guy on the Yankees told me there was great fly-fishing at Big Gunpowder Falls River in Maryland,” Ted said as we bumped down the dirt road. “I always wanted to come here.”

We drove a couple of miles until we reached the river. Ted pulled over. He looked excited as we got out of the car, like a little kid going to an amusement park for the first time.

He opened the back, and on top of everything else in there was a shotgun.

“You keep a shotgun in your car?” I asked. “Isn't that dangerous?”

“Only to the stuff I shoot,” Ted replied.

I have nothing against guns myself. Some of my friends at home like to shoot. But I must have made a face or something.

“Animals die,” Ted said as he rooted around in the back of the station wagon, “and nature's more ruthless than bullets. Some folks pay a butcher to do their killing. I'd rather do it myself.”

He found what he was looking for: a goofy-looking tan hat, which he put on his head. Then he smeared some grease on his lips and sprayed smelly bug spray all over both of us.

Besides the shotgun, the back was filled with fishing rods, a tackle box, bags of feathers, a bunch of boxes of Quaker Oats, and a telescope. I assumed that he got paid by Quaker Oats to endorse the product. But a

telescope

?

“I like to watch the stars,” he explained.

He took out some of the fishing gear, and I followed him down to the water. We seemed to have the whole river to ourselves. There was a little motorboat tied up to a wooden dock. Ted looked both ways and then climbed into the boat as if it was his own.

“Isn't this stealing?” I asked.

“Borrowing,” he said. “Get in.”

I had done a little fishing with my dad when I was younger, but I'd never tried fly-fishing before. Ted explained that you don't use a lure or a sinker, and you don't use a worm. You use a little “fly,” which weighs next to nothing and is made of animal fur, feathers, tinsel, and other stuff to attract fish.

Ted opened his tackle box and showed me a bunch of colorful flies he had made himself. They looked sort of like insects but with hooks sticking out of the bottom. He chose one and expertly tied it to the line. The rod was in two pieces, and he screwed the pieces together. Then he pulled the cord to start the motor, and we headed out on the water. Ted said he had the feeling that this river was full of trout.

We headed out on the river.

He cruised around for a few minutes until he found a spot he liked. He had only brought one fishing rod

out of his car, so I figured this would be a relaxing time for me. I leaned back and put my hands behind my head.

“Get up!” Ted barked. “You don't fish sitting down. Didn't your dad teach you

anything

?”

“Okay! Okay!” I said, jumping to my feet.

“If you're gonna do something, do it right,” Ted said, handing me the rod. “I don't care what it is. Hitting a baseball, catching a fish, whatever.”

The rod was long, maybe eight feet, and much lighter than my fishing pole back home. But the line was heavier. Ted showed me how to “shake hands” with the rod and to point my thumb at the target.

Because there's no lure or sinker to provide weight, fly-fishing requires a different kind of cast. You have to sort of throw the line itself, and the weight of the line carries the hook. Ted took the rod from me to demonstrate.

“Watch,” he said as he brought the rod up over his head. “Backcastâ¦and frontcast.”

He effortlessly flicked the fly forward, then back over his shoulder, and then forward again. The fly would curl over the line in a smooth arc and settle gently on the water. There was something beautiful about it.

I noticed that he fished right-handed. Ted told me that he also wrote, threw, and did pretty much everything with his right hand. The only thing he did lefty was hit a baseball.

“Here, you try,” he said.

I took the rod and tried to do it like he did it. Of course, I failed. The fly flew into the boat, and the hook caught on Ted's shirt. But for a change, he didn't get mad. He just removed the hook and told me to try again.

“Keep a relaxed grip on the rod,” he instructed. “Don't break your wrist at all. Use your forearm.”

“Like this?”

“There you go,” Ted said. “Now you're cooking with gas.”

I was starting to get the hang of it. Ted looked across the water, his hands on his hips, while I flicked the line back and forth, perfecting my cast. He was staring at the river with the same intensity he stared at a pitcher about to go into a windup.

“Cast it over there,” Ted told me, pointing. “Trout like to face upstream. That's where their food comes from. They like to hang around where the fast and slow water mix.”

He maneuvered the boat to change the angle while telling me to bend my knees, check the drag on the line, and cast the fly where he wanted it. He may have had no patience with people, but he had plenty of patience with fish. Fishing seemed to calm him down.

Not me. After five minutes, I was bored and ready to give up. It didn't look like there were any trout out there. We were wasting our time, and I said so.

“I don't like failure,” Ted said.

“Ever.”

I kept casting out the fly, but I didn't feel any

nibbles. My arms were getting tired.

“I see one,” Ted said suddenly.

“Where?”

“Over there,” he said. “See it? See that stitch on the surface of the water? It looks like a zipper.”

I didn't see anything. But I remembered reading in one of my baseball books that Ted Williams had incredible eyesight, better than 20â20. Maybe he could see things that normal people couldn't. I handed him the rod, and he took over.

He was staring intently at the water, flicking the line back and forth as he tried to land the fly on a specific spot where he had seen the fish.

“You

know

you want it,” Ted said as if the fish could understand English. “Come on. Take it, baby.

Take

it.”

And then, suddenly, the line got taut.

“Got 'im!” Ted shouted.

The tip of the rod bent. Ted held the line in one hand to control the tension. Then he pulled in the fly line with his reel hand while he pinched the line with his rod hand. I could see the fish now. It was struggling to escape, darting back and forth.

“He's going left!” Ted said excitedly. “Look at him! Oh, he's a beauty! He's going right now. Watch him, he's gonna jump.”

As if on command, the fish exploded out of the water and up in the air. Ted played it, worked it, reeled it in slowly, talking the whole time.

“He's getting a little tired now,” he said. “He might

have one good burst of energy left in him. I'm gonna let him run, wear himself outâ”

Right after he said that, the most amazing thing happened. The fish came swimming toward us, leaped out of the water, and landed right in the boat!

I freaked out, falling backward and landing on the tackle box. Stuff went flying everywhere. Ted was right. It

was

a beautiful fish. Maybe two feet long. The boat was rocking back and forth, and I was afraid that Ted was going to fall into the river. The fish was probably as freaked out as I was. He didn't know

what

was going on. Ted threw his head back and was laughing like it was the funniest thing he had ever seen.

“Grab him!” he yelled.

“I can't! He's flopping all around!”

“Get the hook out of his mouth!” Ted yelled.

“

You

get the hook out of his mouth!”

I must admit, I always thought it was kind of gross to take a hook out of a fish's mouth. When I used to go fishing with my dad, he always did it for me because I found the whole process to be a little disgusting.

“Here, let

me

do it,” Ted said, dipping his hands into the water. “Trout are delicate. If your hands are dry, you might pull off his scales.”

The fish had stopped flopping around on the bottom of the boat. Ted picked it up and held it tenderly, like it was a baby. He carefully removed the hook and brought the fish to the side of the boat.

“You're gonna let him go?” I asked.

“He put up a good fight.”

Ted lowered the fish into the river, turning it to face upstream, he said, so water could wash through its gills and revive it. He held it there.

“If you let it go too soon,” he said, “it won't have the energy to swim. It'll sink to the bottom and suffocate.”

After thirty seconds or so, the fish began to wriggle around in Ted's hands.

“He's gonna make it,” Ted said. “He's all right.”

Ted let the fish go, and we watched it swim away.

He was calm again. Being with Ted was like hanging out with Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. I thought he was going to switch gears and start yelling at me because of my pathetic fishing skills, but he didn't.

“You're not half bad with a rod and reel,” he said. “How are you with a bat? You play ball?”

“Oh, yeah,” I told him. “Back home, baseball is the only game I play.”

“What do you hit?” Ted asked.

“Around .270.”

He spit in the water, a disgusted look on his face. I guess that to a guy who can hit .400, somebody who can't even hit .300 must look really pathetic.

“How many homers?” he asked me.

“I only had a couple,” I admitted. “One of them was inside the park.”

“Inside the park?” Ted said, looking even more disgusted. “You're a big, strong kid. You should be

driving the ball over the wall. What's your problem?”

“I don't know,” I told him. “I strike out, ground out a lot.”

“Lemme see your batting stance.”

“Right here in the boat?” I asked.

“Of

course

right here in the boat!” Ted shouted. “Where else are you going to do it?”

I got into my stance, being careful to put my weight over the middle so I wouldn't tip the boat. Ted looked me up and down, then shook his head sadly and spit into the water again.

“No wonder you hit .270!” he said. “You're dancing around like you got ants in your pants. Who told you to hit like that?”

“My coach,” I said.

“Your coach is an idiot,” Ted declared. “What position did

he

play?”

“He was a pitcher,” I said.

“A

pitcher

?” Ted said the word “pitcher” as if it was something you scraped off the bottom of your shoe. “There's only one thing in this world that's dumber than a pitcher.”

“What?” I asked.

“

Two

pitchers!” Ted said. “Pitchers should never be allowed anywhere

near

a bat much less teach kids how to use one.”

I considered telling Ted about the designated hitter rule, but I didn't want to push my luck.

“It's about time you learned how to hit a baseball properly, Junior,” he told me.

“Right here?” I asked. “In the boat?”

“Of course right here in the boat!” he exclaimed.

I was about to get a personal hitting lesson from the greatest hitter in the world.

The Happy Zone

“H

ITTING A BASEBALL

,” T

ED TOLD ME

, “

IS THE SINGLE MOST

difficult thing to do in sports.”

We were sitting in the little boat, in a cove where the water was still. The air smelled clean, cleaner than I remembered it in my time. Birds were chirping. It was nice. Ted pulled a couple of packages of crackers out of his pocket and shared them with me.

“Think about it,” he said. “For starters, they give you a round ball and a round bat and tell you to hit it square. The difference between a line drive and a pop-up is just a fraction of an inch on the bat. To make things even more difficult, the pitcher could be throwing a fastball, curve, change-up, or some other !@#$%! pitch he's got up his sleeve. He could throw it inside, outside, high, low; or he might just try to

brain

you with it. Then there are nine very athletic guys in the field trying to catch any ball you hit, and they've

got big gloves on their hands. Plus, there's thousands of idiots in the stands screaming that you're a bum. That's why the best hitters in the game fail seven out of every ten times they come to bat.”

“Or six, in your case,” I said.

Ted ignored my compliment. Maybe he didn't like compliments.

“Because you're a good kid, I'm going to tell you everything I know about hitting a baseball. Now, do you know what the Bernoulli principle is?”

“The

what

?”

“How do you expect to hit a curveball if you never heard of the Bernoulli principle?”

Ted told me that Daniel Bernoulli was an eighteenth-century Swiss mathematician who figured out why objects move through air or water the way they do.

“When a ball spins, the flow of air around it becomes turbulent,” he explained. “One side of the ball is spinning in the same direction as air rushing by, and the other side of the ball spins against the air flow. This causes a difference of air pressure between the two sides of the ball, and the ball moves in the direction of least resistance.”

I had

no

idea what he was talking about.

“You gotta know this stuff!” he hollered.

“Okay, okay!”

I couldn't believe I was getting a physics lesson from Ted Williams. The guy never even went to college.

“There are three keys to hitting,” Ted told me.

“The first one is that you need to get a good ball to hit. Now, do you know where your happy zone is?”

“Uh, that's kind of personal,” I said.

“No, you idiot!” Ted exploded. “Look, home plate is 17 inches wide. That's seven baseballs. Even a moron like you knows it's easier to hit a pitch that's over the center of the plate than one that's on the corner. The middle of the plate is your happy zone.”

“But I can't control where the pitcher is going to throw the ball,” I said.

“Sure you can!” Ted said. “That brings me to the second key to hitting: use your head. It's not just about muscles and reflexes. You want to

force

the pitcher to put the ball in your happy zone.”

“How do I do that?” I asked.

“By refusing to swing at a bad ball,” Ted said. “If you swing at a pitch that's one inch off the plate, the next time you come up, the pitcher will throw it

two

inches off the plate. Then three inches. Pitchers will learn they don't have to throw strikes to you, and you'll never get a good pitch to hit. So if you swing at bad pitches, you make trouble for yourself down the road.”

“Okay, I'll only swing at pitches in my happy zone,” I said.

“Right. Do you know why home run hitters strike out more than singles hitters?” Ted asked.

“Because they swing harder?” I guessed.

“No! Because they're

stupider

,” Ted said. “They go after more bad pitches. That's dumb. Don't chase bad

balls. Don't give away strikes. Use your head.”

“Okay, got it,” I said. “Use my head.”

“That also means you need to use the rules of the game,” Ted continued. “You've got three strikes and four balls to make the situation into what you want it to be. So if the count is 0 and 2, you're almost sure to get a pitch off the plate. Don't swing at that junk. But if the count is 2 and 0, the pitcher doesn't want to throw ball three, so you're gonna get a fastball close to your happy zone. Bet on it. Know the count. Use the count. Use your head.”

At that point, Ted reached into his back pocket and pulled out a little black address book.

“What's that?” I asked. “A list of your girlfriends?”

“No!” Ted yelled at me. “It's a list of every pitcher in the American League. What they throw. When they throw it. Their strengths. Their weaknesses. If you want to be successful at something, you have to know

everything

about it.”

Ted told me he would notice the heights of the different pitcher's mounds in various ballparks and write them in his little black book. He studied the wind patterns of every ballpark. He knew which batter's boxes sloped up a little and which ones sloped down. While the other players would sit in the clubhouse playing cards before the game, he would sit by himself in the dugout and study the pitcher warming up. Every day, he pored over the box scores in the newspaper searching for some little tidbit of information that might help him when he came to bat.

“You gotta know this stuff,” Ted told me. “Is the wind blowing in or out? Is it a damp day? The ball won't travel as far. And you have to constantly make adjustments. If you ground out a lot, that means you're swinging too early. If you pop up a lot, you're swinging too late. Use your head.”

He was throwing so much information at me, and so quickly, it was hard to absorb it. But it all made sense, and I was trying to take in every word.

“Okay,” I said, “so the first key to hitting is to get a good ball to hit. The second key is to use my head. What's the third key?”

“The third key is to be quick,” Ted said. “Tell me, how heavy is your bat?”

“Thirty-two ounces,” I replied. My coach, Flip, had told me that was the right weight for my age and size.

“Are you out of your mind?” Ted sputtered. “I use a 32-ounce bat, and I'm a lot stronger than you are. Look, the pitcher's mound is 60 feet and 6 inches away. If a pitcher throws 90 miles per hour, the ball will reach the plate about a half a second after it leaves his hand. So you have a

fraction

of a second to make up your mind whether or not to swing.”

“So you're saying I should switch to a lighter bat?” I asked.

“Of

course

!” Ted exclaimed. “You can swing it quicker. And if you have a quicker swing, you can wait longer before deciding whether or not to commit. And the longer you wait, the less chance you're going

to get fooled by the pitch. Bat speed is

everything

.”

Ted told me to stand up and show him my batting stance again. When I did, he pushed and pulled at my arms and legs to get them into the proper position.

“Weight balanced,” he said. “Knees bent and flexible. Keep your head still. Hold your bat upright, almost perpendicular. It feels lighter that way. Grip the bat firmly. And when you pull the trigger, you want to swing in a slight uppercut.”

“My coach told me I'm supposed to swing level,” I said.

“I already told you, your coach is a moron,” said Ted. “The pitcher's mound is 15 inches higher than home plate. The pitcher releases the ball a foot over his head. And gravity makes the ball go

down

. How are you gonna hit it squarely if you swing level? You have to swing

up

at it.”

Everything Flip had taught me, it seemed, was wrong. Flip never pretended to be an expert in hitting. His advice usually boiled down to “See the ball. Hit the ball.” But Ted was analytical, even scientific, about hitting a baseball. He was the same way about fishing, and he would become the same way about flying a fighter plane. Probably, it was the same way he was about everything.

“One last thing,” he said. “Did you ever hear that joke about how to get to Carnegie Hall?”

“Practice,” I said.

“It's the same thing with hitting,” Ted told me.

“There are thousands of kids out there who have natural ability. Practice is what separates good players from great ones. There's no substitute for hard work. When I was your age, I practiced until my blisters bled.”

My batting lesson was over. Ted yanked the cord to start the motor. My head was spinning from all he had told me:

the Bernoulli principleâ¦Get a good pitch to hitâ¦. Use your headâ¦. Be quickâ¦. Use a lighter batâ¦. Swing up at the ballâ¦. Practice until your fingers bleed.

“Let's get out of here,” Ted said as we

putt-putt

ed upstream. “We have to get to Washington to tell the president about that Pearl Harbor thing, and I hear he goes to bed early.”