Ted & Me (12 page)

Authors: Dan Gutman

Visiting a Friend

T

ED STEERED THE BOAT BACK TO THE DOCK AND TIED IT UP

. He tucked a dollar bill into one of the seat cushions to pay for the gas we used. We climbed out and stashed the fishing gear back in his car. Soon we were off the dirt road and back on Route 1 heading south.

There wasn't much to look at for a few miles. Farms and farm stands mostly. We didn't talk much. As I looked out the window, I imagined that in the twenty-first century, this road would probably be jammed with fast-food joints and strip malls. Maybe Route 1 wouldn't even exist anymore. A superhighway might cover this area. It was kind of sad.

After a while, we began to see some houses, businesses, and bigger buildings. From reading the signs along the road, I realized we had reached the city of Baltimore.

“I gotta make a quick stop here,” Ted said suddenly,

pulling off the road.

What is it

this

time,

I wondered. Was he going to take out his shotgun for some target practice? He seemed to impulsively stop and do something completely different whenever he felt like it. It was getting late. Maybe we'd

never

get to Washington.

Ted pulled into a parking lot. The sign said

ST. LUKE'S HOSPITAL.

. As we got out of the car, he grabbed a baseball from the backseat.

“What are we doing here?” I asked.

“I need to visit a friend,” he replied. “It won't take long.”

There was no security guard in the lobby. Ted and I walked right in, and he led me down a series of hallways. He was looking for a room number.

“What's wrong with your friend?” I asked.

“Nobody knows,” Ted replied. “He's dying.”

He stopped outside Room 125 and opened the door a crack.

There were two beds in the room. One was empty, and a boy was lying in the other one. He looked younger than me, probably nine or ten. His eyes were closed, but he opened them when the door squeaked. He brightened when he saw Ted.

“Hey, knucklehead!” Ted said. “What's buzzin', cousin?”

“Nothin',” the boy answered weakly. I could barely hear him.

“This is my pal Stosh,” said Ted. “Stosh, this is Howie.”

I went to shake hands with the boy, but he could barely raise his arm. I picked his hand up for him and shook it.

“I brought you something, big guy,” Ted said, picking up a pen from the little table next to the bed. Then he signed the baseball and put it next to Howie.

“I heard on the radio that you did it,” Howie said.

“Did what?”

“Hit .400.”

“Oh, yeah,” Ted said. “.406. But who's counting? Hey, did they say anything on the radio about the alligator?”

Howie started laughing.

“It bit some kid's leg off!” Ted said, shaking his head. “Awful thing. At the knee. The kid's in terrible shape. Have you seen that alligator around here?”

Howie laughed some more.

“You always say that,” he said.

“What's this?” Ted said as he picked up some papers from the table. “Your homework? I see you left some of the answers blank.”

“What's the point?” Howie asked.

I knew what he was saying. Homework is a drag. I don't like doing it either; and if I knew that I was going to die soon, I sure wouldn't want to bother spending the time I had left doing homework.

“This stuff makes you smart,” Ted told Howie. “You don't want to grow up and become a dummy like me, do ya?”

Howie didn't answer. He didn't need to. They both knew he wasn't going to grow up.

“I'm tired,” he said, taking Ted's finger in his little hand.

“Hey, you got a good grip on you,” Ted said cheerfully. “How do you expect me to hit .400 next year with a crushed finger?”

Howie laughed. He kept holding Ted's finger. Ted reached into a pocket with his other hand and came out with a ten-dollar bill. He put it on Howie's bed next to the baseball.

“Tell your mom to buy you something nice with this,” he said.

Howie closed his eyes, still gripping Ted's finger. Ted told him about the World Series coming up between the Yankees and the Dodgers. He discussed the pitching matchups, and which hitters he thought would come through in a big game. He said he was rooting for the Yankees because they were the American League team, and besides, Dom DiMaggio's brother played for them.

Howie looked like he was asleep, but I wasn't sure. He kept holding on to Ted's finger, and it didn't look like he was planning on letting go anytime soon.

Ted kept talking softlyâabout baseball, the weather, food, movies he had seen, anything he could think of. Howie didn't respond, but he wouldn't let go of Ted's finger. At some point, I noticed a tear come out of Ted's eye and roll down his face.

Soon after, Ted fell asleep in the chair, with Howie still attached to his finger. It looked as though we would be spending the night there, so I climbed into the other bed and went to sleep.

An American Hero

“W

AKE UP

!”

This time Ted whispered it in my ear.

I was a little freaked out to open my eyes and find myself in a hospital bed. It took a few seconds to remember how I got there. Little Howie was asleep in the bed next to mine. He must have finally let go of Ted's finger. Ted gestured for me to follow him, and we tiptoed out the door.

Back in the car, Ted said it was only about 40 more miles to Washington. We were getting close. I started thinking about what I would say to President Roosevelt. That is, if we could manage to get inside the White House.

“How do you know they'll let us meet the president?” I asked.

“I'm Ted !@#$%! Williams, that's how.”

We got back on Route 1 heading south. I wasn't

paying much attention to the scenery passing by because I was too nervous thinking about what might happen to us in Washington. What if we got to the White House, and the security guard wasn't a baseball fan? Maybe he never heard of Ted. Or what if we got inside to see President Roosevelt, and he didn't believe me when I told him what's going to happen at Pearl Harbor? What if he thought I was crazy and had me thrown in jail or something? I just hoped that Ted's fame would overcome those problems. With luck, people would take one look at him and believe what we had to say.

We were driving through flat, endless farm country. Hardly any signs or people. The only stations the radio could pick up were filled with static. It seemed like a good time to talk to Ted about the

other

reason I had come to see him.

“I did some research on you,” I told him. “If you play baseball instead of joining the marines, you're likely to get about 500 at-bats each year. In four years, that would come to 2,000 more career at-bats.”

“So?” Ted asked.

“Well,” I continued, “if you hit one home run in every ten at-bats, you'll hit another 200 homers in your career. As it is, you're going to end up with 521 homers. But adding 200 more would bring the total to 721.”

“So?” Ted asked.

“Babe Ruth hit 714 in his career,” I told him. “So if you stay out of the military and play ball instead,

there's a good chance you'll retire with more homers than Ruth.”

Ted thought about that for a moment and then shook his head.

“I don't care about home runs,” he said, “and I don't care about beating Ruth either.”

“But the other night you told me your dream was to walk down the street and have people call you the greatest hitter who ever lived,” I said.

“I don't care about that anymore,” Ted replied.

“Why not?”

I was starting to panic. I must have done something, or said something, that changed his mind. Maybe I had messed up history without knowing it. Maybe I stepped on that twig in the forest.

“Hitting a baseball just doesn't seem so important anymore,” Ted told me. “If this Pearl Harbor thing is going to happen like you said, all those guys are going to die. I have to stop it. Some things are more important than hitting home runs.”

We drove on in silence for a few miles. I was thinking about all those people who were going to die. Ted was probably thinking about them too.

“You and me, we're lucky to be born here,” he said out of the blue. “It gave us the chance to be the best in the world at something. If I was born in some other country, I wouldn't have hit .400. I wouldn't be rich and famous. None of this would have happened.”

“You mean because they don't play baseball in other countries?” I asked.

Ted looked at me like I was stupid.

“The United States is the only country in the world where it doesn't matter who your parents are or how much money you have,” he told me. “A dirt-poor half-Mexican kid like me can grow up to become rich and famous. He can play ball or invent something, start a company or even become president.”

“That's what they say.”

“Because it's true,” Ted told me. “

That's

why this country is great. You know what the most important part of the word âAmerican' is? The last four letters: I C-A-N.”

As I let that sink in, the road took us into a small town with a few churches, a firehouse, and a ball field. There were people gathered on the field, lots of them. At first I thought there might be a game going on; but the people were standing all over the field, and some of them were carrying signs. We were too far away for me to read them.

“What's going on?” I asked.

“That's another reason why our country is great,” Ted said. “These folks are protesting something or other. The United States is one of the few places in the world where people have freedom of speech, y'know. If they protested like this in some other country, they'd get locked up.

This

is what America is all about.”

We had to slow down to a crawl because there were so many people milling around in the road. I

saw a big sign on the outfield fenceâ¦.

RALLY FOR AMERICA FIRST!

SPEAKING TODAY: CHARLES LINDBERGH

“Lucky Lindy!” Ted said excitedly. “He was my hero growing up. I was eight years old when he made the first solo flight across the Atlantic. He was

everybody's

hero. No wonder all these people are here.”

Ted pulled the car off to the side of the road and opened the door.

“Don't you think we should just keep on driving to Washington?” I asked.

“Plenty of time for that,” Ted replied. “How often do you get to see a real American hero? Come on!”

As we crossed the street and walked toward the rally, Ted told me something I didn't know about Charles Lindbergh. A few years back his baby, Charles Jr., was kidnapped in the middle of the night right out of his crib. The police found the boy's body a few months later. What a horrible thing to happen to anyone. I felt sorry for him. Lindbergh and his wife were so devastated that they went to live in England for a few years.

The rally was open to the public. I could hear chanting, and now we were close enough to read the signs the people were holding upâ¦

KEEP AMERICA OUT OF THE WAR!

LET EUROPE FIGHT ITS OWN BATTLES!

STAY OUT OF FOREIGN WARS!

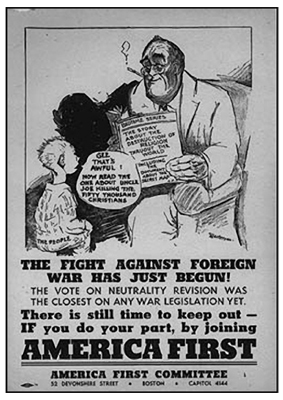

Some guy handed me a flyerâ¦.

I always thought everybody supported that war.

So it was an antiwar rally. I had heard about the antiwar movement during the Vietnam War, but I didn't know they had them before that. I always thought that back in the old days, Americans pretty much agreed on political stuff. Not like today when everybody seems to just argue about everything. Maybe I was wrong.

There was a stage with a podium on it set up near second base, some American flags, and a banner that said

DEFEND AMERICA FIRST

. Charles Lindbergh wasn't onstage yet, but the crowd was already pumped up. People were clapping, shouting at each other, and

passing out buttons and pamphlets.

“Let England and France fight their

own

wars,” shouted one guy.

“Let the Nazis wipe out the commies!” yelled somebody else. “Keep us out of it.”

As Ted and I moved through the crowd, I didn't have a good feeling. These people weren't peace-loving hippies. They looked angry. I patted my back pocket to make sure I still had my pack of new baseball cards, just in case I needed them.

A pretty woman wearing a

NO WAR

button stepped in front of Ted.

“Hey there, handsome,” she said, smiling, “did anybody ever say you look like Ted Williams, that baseball player?”

“Actually, miss,” Ted replied with a smile, “I

am

Ted Williams, that baseball player. And what's your name? I bet it's as pretty as you are.”

The girl said her name was Bonnie, and she just about fainted upon realizing that the guy she thought looked like Ted actually

was

Ted. She told him that he was her favorite player and that she had pictures of him all over her room. Ted started singing “My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean” while Bonnie fussed with her purse until she came up with a pen and a piece of paper.

“Can I have your autograph?” she begged. “Please? Please? Please?”

“I'll make a deal with you,” Ted told her. “I'll give you my autograph if you give me your phone number.”

“Sure thing, honey!”

Neither of them paid any attention to

me

, of course. Ted and Bonnie flirted with each other while he signed her paper.

As soon as he started writing on it, I heard people around us asking, “Who's that guy?” and “Is he somebody famous?” It didn't take long for people to realize it was Ted Williams. Scraps of paper and pens appeared almost as if by magic and were thrust in Ted's face from all sides. In seconds, he was surrounded by a crush of autograph seekers. It looked like he was almost as popular as Charles Lindbergh.

“It's Ted Williams!” some girl squealed. “The guy who hit .400!”

I wasn't sure what to do. Ted looked up over the heads of his admirers and caught my eye.

“I'll catch up with you later, Stosh,” he said.

I wandered around the crowd, trying to get closer to the stage. It would be cool to see the famous Charles Lindbergh close-up. There were more signs up front:

FREE SOCIETY OF TEUTONIA and FRIENDS OF NEW GERMANY.

Suddenly, on one side, the crowd broke out into cheers and applause. A man climbed up on the small stage. He was wearing a jacket and tie. As he stepped up to the microphone and a roar went up, I realized he was Charles Lindbergh.

“Lindy! Lindy! Lindy!”

He was a handsome man, and over six feet tall. He looked to be less than forty but seemed confident and sure of himself. I was close enough to see

that he had a dimple in his chin. Lindbergh waved and waited until the crowd calmed down before he started to speak.

Charles Lindbergh

“It is now two years since this latest European war began,” he said. “From that day in September 1939 until the present moment, there has been an ever-increasing effort to force the United States into the conflict.”

“Booooooooooooooo!”

shouted the crowd.

They weren't booing Lindbergh, I gathered. They were booing because they didn't want the United States to enter the war.

“We, the heirs of European culture, are on the verge of a disastrous war, a war within our own family

of nations, a war which will reduce the strength and destroy the treasures of the white race.”

“That's right!” somebody yelled.

What? I wasn't sure if I heard him right. Did he say “the white race”? In my time, people who use terms like “the white race” are usually white racists.

It took a minute for it to sink in that I was listening to a racist speech. We had learned about Charles Lindbergh's famous flight in school. But I didn't remember hearing that he was a bigot. Maybe I was absent that day.

“There are three important groups who have been pressing this country toward war,” Lindbergh continued, “the Roosevelt administration, the British, and the Jewish.”