The $100 Startup: Reinvent the Way You Make a Living, Do What You Love, and Create a New Future (4 page)

Authors: Chris Guillebeau

Others pursued partnerships that allowed each person to focus on what he or she was best at. Fresh out of design school and disillusioned with their entry-level jobs, Jen Adrion and Omar Noory began selling custom-made maps out of an apartment in Columbus, Ohio. Patrick McCrann and Rich Strauss were competitors who teamed up to create a community for endurance athletes. Several of our stories are about married couples or partners building a business together.

But many others chose to go it alone, with the conviction that they would find freedom by working primarily by themselves. Charlie Pabst was a successful architect with a “dream job” as a

store designer for Starbucks. But the desire for autonomy overcame the comfort of the dream job and the free lattes: “One day I drove to work and realized I couldn’t do it anymore, called in sick, drafted my two-week notice, and the rest is history.” Charlie still works as a designer, but now he works from home for clients of his choosing.

We’ll view these stories as an

ensemble

: a group of individual voices that, when considered together, comprise an original composition. In sharing how different people have set themselves free from corporate misery, the challenge is to acknowledge their courage without exaggerating their skills. Most of them aren’t geniuses or natural-born entrepreneurs; they are ordinary people who made a few key decisions that changed their lives. Very few of our case studies went to business school, and more than half had no previous business experience whatsoever. Several dropped out of college, and others never went in the first place.

*

In sharing these stories, the goal is to provide a blueprint for freedom, a plan you can use to apply their lessons to your own escape plan. Throughout the case studies, three lessons of micro-entrepreneurship emerge. We’ll focus on these lessons in various ways throughout the book.

As we’ll examine it,

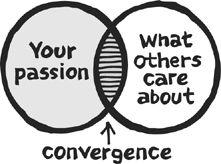

convergence

represents the intersection between something you especially like to do or are good at doing (preferably both) and what other people are also interested in. The easiest way to understand convergence is to think of it as the overlapping space

between what you care about and what other people are willing to spend money on.

Consider these circles:

Not everything that you are passionate about or skilled in is interesting to the rest of the world, and not everything is marketable. I can be very passionate about eating pizza, but no one is going to pay me to do it. Likewise, any individual person won’t be able to provide a solution to every problem or be interesting to everyone. But in the overlap between the two circles, where passion or skill meets usefulness, a microbusiness built on freedom and value can thrive.

Many of the projects we’ll examine were started by people with

related

skills, not necessarily the skill most used in the project. For example, teachers are usually good at more than just teaching; they’re also good at things such as communication, adaptability, crowd control, lesson planning, and coordinating among different interest groups (children, parents, administrators, colleagues). Teaching is a noble career on its own, but these skills can also be put to good use in building a business.

The easiest way to understand skill transformation is to realize

that you’re probably good at more than one thing. Originally from Germany, Kat Alder was waitressing in London when someone said to her, “You know, you’d be really good at PR.” Kat didn’t know anything about PR—she wasn’t even sure it stood for “public relations”—but she knew she was a good waitress, always getting good tips and making her customers happy by recommending items from the menu that she was sure they would like.

After she was let go from another temporary job at the BBC, she thought back on the conversation. She still didn’t know much about the PR industry, but she landed her first client within a month and figured it out. Four years later, her firm employs five people and operates in London, Berlin, New York, and China. Kat was a great waitress and learned to apply similar “people skills” to publicizing her clients, creating a business that was more profitable, sustainable, and fun than working for someone else and endlessly repeating the list of daily specials.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, success in entrepreneurship isn’t necessarily related to being the best at any particular activity. Scott Adams, the creator of the

Dilbert

comic series, explains his success this way:

I succeeded as a cartoonist with negligible art talent, some basic writing skills, an ordinary sense of humor and a bit of experience in the business world. The “Dilbert” comic is a combination of all four skills. The world has plenty of better artists, smarter writers, funnier humorists and more experienced business people. The rare part is that each of those modest skills is collected in one person. That’s how value is created.

†

To succeed in a business project, especially one you’re excited about, it helps to think carefully about all the skills you have that could be helpful to others and particularly about the combination of those skills.

Bringing the first two ideas together, here is the not-so-secret recipe for microbusiness alchemy:

Passion or skill + usefulness = success

Throughout the book, we’ll examine case studies by referring to this formula. Jaden Hair forged a career as the host of

Steamy Kitchen

, a cooking show and website featuring Asian cuisine. From an initial investment of $200, cookbooks, TV offers, and corporate sponsorship have all come her way due to the merging of passion and usefulness. The recipes Jaden shares with a large community on a daily basis are easy, healthy, and very popular—when I met her at an event she was hosting in Austin, I could barely get through the throngs of admirers to say hi. (Read more of Jaden’s story in

Chapter 2

.)

Elsewhere, Brandon Pearce was a piano teacher struggling to keep up with the administrative side of his work. A programming hobbyist, he created software to help track his students, scheduling, and payment. “I did the whole project with no intention of making it into a business,” he said. “But then other teachers started showing interest, and I thought maybe I could make a few extra bucks with it.” The few extra bucks turned into a full-time income and more, with current income in excess of $30,000 a month. A native of Utah, Brandon now lives with his family at their second home in

Costa Rica when they aren’t exploring the rest of the world. (Read more of Brandon’s story in

Chapter 4

.)

In the quest for freedom, we’ll look at the nuts and bolts of building a microbusiness through the lens of those who have done it. The basics of starting a business are very simple; you don’t need an MBA (keep the $60,000 tuition), venture capital, or even a detailed plan. You just need a product or service, a group of people willing to pay for it, and a way to get paid. This can be broken down as follows:

1. Product or service: what you sell

2. People willing to pay for it: your customers

3. A way to get paid: how you’ll exchange a product or service for money

If you have a group of interested people but nothing to sell, you don’t have a business. If you have something to sell but no one willing to buy it, you don’t have a business. In both cases, without a clear and easy way for customers to pay for what you offer, you don’t have a business. Put the three together, and congratulations—you’re now an entrepreneur.

These are the bare bones of any project; there’s no need to overcomplicate things. But to look at it more closely, it helps to have an

offer

: a combination of product or service

plus

the messaging that makes a case to potential buyers. The initial work can be a challenge, but after the typical business gets going, you can usually take a number of steps to

ramp up

sales and income—if you want to. It helps to have a strategy of building interest and attracting attention,

described here as

hustling

. Instead of just popping up one day with an offer, it helps to craft a

launch event

to get buyers excited ahead of time.

We’ll look at each of these concepts in precise detail, down to dollars-and-cents figures from those who have gone before. The goal is to explain what people have done that works and closely examine how it can be replicated elsewhere. The lessons and case studies illustrate a business-creation method that has worked many times over: Build something that people want and give it to them.

There’s no failproof method; in fact, failure is often the best teacher. Along the way, we’ll meet an artist whose studio collapsed underneath him as he stood on the roof, frantically shoveling snow. We’ll see how an adventure travel provider recovered after hearing that the South Pacific island they were taking guests to the next morning was no longer receiving visitors. Sometimes the challenge comes from too much business instead of too little: In Chicago, we’ll see what happens when a business struggles under the weight of an unexpected two thousand new customers in a single day. We’ll study how these and other brave entrepreneurs forged ahead and kept going, turning potential disasters into long-term successes.

The constant themes in our study are freedom and value, but the undercurrent to both is the theme of change. From his home base in Seattle, James Kirk used to build and manage computer data centers around the country. But in an act of conviction that took less than six months from idea to execution, he packed up a 2006 Mustang and left Seattle for South Carolina, on a mission to start an authentic coffee shop in the land of biscuits and iced tea. Once he made the decision, he says, all other options were closed: “There was one moment very early on when I realized, this is what I want

to do, and this is what I am going to do. And that was that. Decision made. I’ll figure the rest out.”

As we’ll see, James later got serious about making a real plan, but the more important step was the decision to proceed. Ready or not, he was heading for a major change, and it couldn’t come soon enough. A few short months later, Jamestown Coffee opened for business in Lexington, South Carolina. James and his new staff had worked ten-hour days for several weeks to prepare for the opening. But there it was: a ribbon to be cut, the mayor on hand to welcome the business to the community, and a line of customers eager to sample the wares. The day had come at last, and there was no looking back.

KEY POINTS

Microbusinesses aren’t new; they’ve been around since the beginning of commerce. What’s changed, however, is the ability to test, launch, and scale your project quickly and on the cheap.

To start a business, you need three things: a product or service, a group of people willing to pay for it, and a way to get paid. Everything else is completely optional.

If you’re good at one thing, you’re probably good at other things too. Many projects begin through a process of “skill transformation,” in which you apply your knowledge to a related topic.

Most important: merge your passion and skill with something that is useful to other people.