The $100 Startup: Reinvent the Way You Make a Living, Do What You Love, and Create a New Future (5 page)

Authors: Chris Guillebeau

*

Jeremy Brown attended two years of technical school but left without graduating. After he founded a successful company, the school invited him back to speak to students as a “success story,” not realizing that his success had come from leaving the program to go out on his own. “The speech was a little awkward,” he says, “but the students liked it.”

†

Scott Adams, “How to Get a Real Education at College,”

The Wall Street Journal

, April 9, 2011.

.

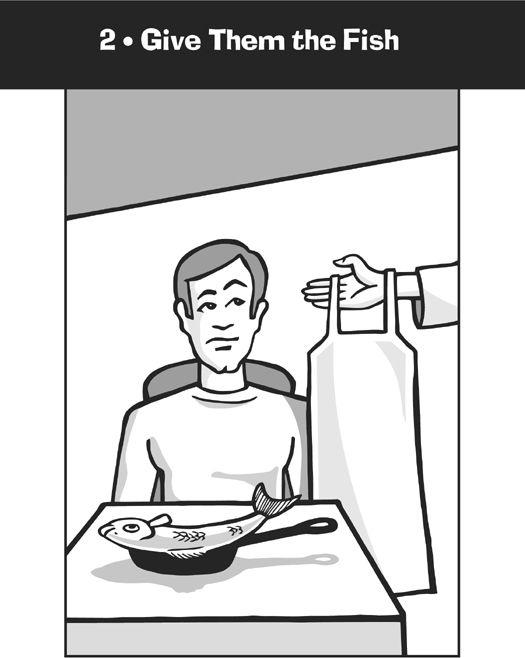

“Catch a man a fish, and you can sell it to him

.

Teach a man to fish, and you ruin

a wonderful business opportunity.”

—KARL MARX

A

long with some of the other stories mentioned briefly in

Chapter 1

, we’ll return to the Jamestown Coffee Company as we go along. But first, let’s consider a key principle of building your way to freedom through a

microbusiness

based on a skill, hobby, or passion. The hard way to start a business is to fumble along, uncertain whether your big idea will resonate with customers. The easy way is to find out what people want and then find a way to give it to them.

Another way to consider it is to think about fish.

Picture this scenario: It’s Friday night, and you head out to a nice restaurant after a long week of work. While you’re relaxing over a glass of wine, the waiter comes over and informs you of the special. “We have a delicious salmon risotto tonight,” he says. “That sounds perfect,” you think, so you order the dish. The waiter jots it down and heads back toward the kitchen as you continue your wine and conversation.

So far, so good, right? But then the chef comes out and walks

over to your table. “I understand you’ve ordered the salmon risotto,” she says as you nod in affirmation. “Well, risotto is a bit tricky, and it’s important we get the salmon right, too … Have you ever made it before?” Before you can respond, the chef turns around. “Tell you what, I’ll go ahead and get the olive oil started.… You wash up and meet me back in the kitchen.”

I’m guessing this experience has never happened to you, and I’m also guessing that you probably wouldn’t enjoy it if it did. After getting past the initial surprise (Does the chef really want me to come back into the kitchen and help prepare the food?), you’d probably find it very odd. You know that the food in the restaurant costs much more than it would in the grocery store—you’re paying a big premium for atmosphere and service. If you wanted to make salmon risotto yourself, you would have done so. You didn’t go to the restaurant to learn to make a new dish; you went to relax and have people do everything for you.

What does this scenario have to do with starting a microbusiness and plotting a course toward freedom? Here’s the problem: Many businesses are modeled on the idea that customers should come back to the kitchen and make their own dinner. Instead of giving people what they really want, the business owners have the idea that it’s better to involve customers behind the scenes … because that’s what they

think

customers want.

It’s all the fault of the old saying: “Give a man a fish and he’ll eat for a day. Teach a man to fish and he’ll eat for a lifetime.” This might be a good idea for hungry fishermen, but it’s usually a terrible idea in business. Most customers don’t want to learn how to fish. We work all week and go to the restaurant so that someone can take care of everything for us. We don’t need to know the details of what goes on in the kitchen; in fact, we may not even

want

to know the details.

A better way is to give people what they actually want, and the way to do that lies in understanding something very simple about who we are. Get this point right, and a lot of other things become much easier.

For fifteen years, John and Barbara Varian were furniture builders, living on a ranch in Parkfield, California, a tiny town where the welcome sign reads “Population 18.” The idea for a side business came about by accident after a group of horseback riding enthusiasts asked if they could pay a fee to ride on the ranch. They would need to eat, too—could John and Barbara do something about that? Yes, they could.

In the fall of 2006, a devastating fire burned down most of their inventory, causing them to reevaluate the whole operation. Instead of rebuilding the furniture business (no pun intended), they decided to change course. “We had always loved horses,” Barbara said, “so we decided to see about having more groups pay to come to the ranch.” They built a bunkhouse and upgraded other buildings, putting together specific packages for riding groups that included all meals and activities. John and Barbara reopened as the V6 Ranch, situated on 20,000 acres exactly halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Barbara’s story stood out to me because of something she said. I always ask business owners what they sell and why their customers buy from them, and the answers are often insightful in more ways than one. Many people answer the question directly—“We sell widgets, and people buy them because they need a widget”—but once in a while, I hear a more astute response.

“We’re not selling horse rides,” Barbara said emphatically. “We’re offering freedom. Our work helps our guests escape, even

if just for a moment in time, and be someone they may have never even considered before.”

The difference is crucial. Most people who visit the V6 Ranch have day jobs and a limited number of vacation days. Why do they choose to visit a working ranch in a tiny town instead of jetting off to lie on a beach in Hawaii? The answer lies in the story and messaging behind John and Barbara’s offer. Helping their clients “escape and be someone else” is far more valuable than offering horse rides. Above all else, the V6 Ranch is selling happiness.

On the other side of the country, Kelly Newsome was a straight-A student and an ambitious Washington, D.C., career climber. By the time she started college, she already had the goal of big career achievement in mind. From the top of her class at the University of Virginia School of Law, she went on to a high-paying job as a Manhattan lawyer—her dream for more than six years. Alas, Kelly soon discovered that dutifully checking the company’s filings for compliance with the Securities Act day in and day out wasn’t exactly what she had hoped for back in law school. After the high of scoring her dream job wore off and the reality of being a well-paid paper pusher set in, Kelly wanted a change.

Abandoning her $240,000-a-year corporate law gig five years in, Kelly left for a new position at Human Rights Watch, the international charity. This job was more fulfilling than the moneymaking job, but it also helped her realize that she really wanted to be on her own. Before the next change, Kelly took time off and traveled the world. Yoga had always been a passion for her, and during her time away, she underwent a two-hundred-hour training course, followed by teaching in Asia and Europe. The next step was Higher Ground Yoga, a private practice she founded back in Washington,

D.C. There were plenty of yoga studios in D.C., but Kelly wanted to focus on a specific market: busy women, usually executives, ages thirty to forty-five and often with young children or expecting. In less than a year, Kelly built the business to the $50,000+ level, and she’s now on track for more than $85,000 a year.

The practice has its weaknesses—during a big East Coast “snowpocalypse,” Kelly was unable to drive to her appointments for nearly three weeks, losing income for much of that time. Despite the lower salary and the problem of losing business during bad weather, Kelly says she wouldn’t return to her old career. Here’s how she put it: “One time when I was a lawyer, having just worked with an outstanding massage therapist, I said to her, ‘It must be so great to make people so happy.’ And it is.” Like Barbara and John in California, Kelly discovered that the secret to a meaningful new career was directly related to making people feel good about themselves.

Where Do Ideas Come From?

As you begin to think like an entrepreneur, you’ll notice that business ideas can come from anywhere. When you go to the store, pay attention to the way they display the signage. Check the prices on restaurant menus not just for your own budget but also to compare them with the prices at other places. When you see an ad, ask yourself: What is the most important message the company is trying to communicate?

While thinking like this, you’ll notice opportunities for microbusiness projects everywhere you go. Here are a few common sources of inspiration.

An inefficiency in the marketplace

. Ever notice when something isn’t run the way it should be, or you find yourself looking for something that doesn’t exist? Chances are, you’re not the only one frustrated, and you’re not the only one who wants that nonexistent thing.

Make what you want to buy yourself, and other people will probably want it too.

New technology or opportunity

. When everyone started using smart phones, new markets cropped up for app developers, case manufacturers, and so on. But the obvious answer isn’t the only one: Makers of nice journals and paper notebooks also saw an uptick in sales, perhaps in part because of customers who didn’t want everything in their lives to be electronic.

A changing space

. As we saw with Michael’s example in

Chapter 1

, car dealerships were going out of business, and he was able to rent his first temporary mattress space on the cheap. Not everyone would have thought of locating a mattress shop in a former car dealership, but Michael grabbed the opportunity.

A spin-off or side project

. One business idea can lead to many others. Whenever something is going well, think about offshoots, spin-offs, and side projects that could also bring in income. Brandon Pearce, whom we’ll see more of in

Chapter 4

, founded Studio Helper as a side project to his main business of Music Teacher’s Helper. It now brings in more than $100,000 a year on its own.

Tip: When thinking about different business ideas, also think about money. Get in the habit of equating “money stuff” with ideas. When brainstorming and evaluating different projects, money isn’t the sole consideration—but it’s an important one. Ask three questions for every idea:

a. How would I get paid with this idea?

b. How much would I get paid from this idea?

c. Is there a way I could get paid more than once?

We’ll look at money issues more in

Chapters 10

and

11

.

The stories of the V6 Ranch and Higher Ground Yoga are good examples of how freedom and value are related. In California, John and Barbara found a way to pursue the outdoor lives they wanted by inviting guests to make the ranch their escape. Meanwhile, even though Kelly makes less money (at least for now) in her new career, her health is better and she does work she enjoys—a trade-off she was happy to make. Freedom was Kelly’s primary motivation in making the switch, but the key to her success is the value she provides her clients.