The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (11 page)

Read The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life Online

Authors: Richard J. Herrnstein,Charles A. Murray

Tags: #History, #Science, #General, #Psychology, #Sociology, #Genetics & Genomics, #Life Sciences, #Social Science, #Educational Psychology, #Intelligence Levels - United States, #Nature and Nurture, #United States, #Education, #Political Science, #Intelligence Levels - Social Aspects - United States, #Intellect, #Intelligence Levels

Sources:

Brigham, 1932; Learned and Wood, 1938.

It is easy to see from the figure above why cognitive stratification was only a minor part of the social landscape in 1930. At any given level of cognitive ability, the number of people without college degrees dwarfed the number who had them. College graduates and the noncollege population did not differ much in IQ And even the graduates of the top universities (an estimate based on the Ivy League data for 1928) had IQs well within the ordinary range of ability.

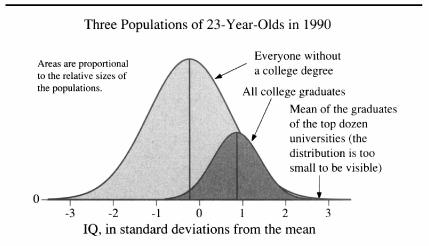

The comparable picture sixty years later, based on our analysis of the NLSY, is shown in the next figure, again depicted as normal distributions.

32

Note that the actual distributions may deviate from perfect normality, especially out in the tails.

Americans with and without a college degree as of 1990

The college population has grown a lot while its mean IQ has risen a bit. Most bright people were not going to college in 1930 (or earlier)—waiting on the bench, so to speak, until the game opened up to them. By 1990, the noncollege population, drained of many bright youngsters, had shifted downward in IQ While the college population grew, the gap between college and noncollege populations therefore also grew. The largest change, however, has been the huge increase in the intelligence of the average student in the top dozen universities, up a standard deviation and a half from where the Ivies and the Seven Sisters were in 1930. One may see other features in the figure evidently less supportive of cognitive partitioning. Our picture suggests that for every person within the ranks of college graduates, there is another among those without a college degree who has just as high an IQ—or at least almost. And as for the graduates of the dozen top schools,

33

while it is true that their mean IQ is extremely high (designated by the +2.7 SDs to which the line points), they are such a small proportion of the nation’s population that they do not even register visually on this graph, and they too are apparently outnumbered by people with similar IQs who do not graduate from those

colleges, or do not graduate from college at all. Is there anything to be concerned about? How much partitioning has really occurred?,

Perhaps a few examples will illustrate. Think of your twelve closest friends or colleagues. For most readers of this book, a large majority will be college graduates. Does it surprise you to learn that the odds of having even

half

of them be college graduates are only six in a thousand, if people were randomly paired off?

34

Many of you will not think it odd that half or more of the dozen have advanced degrees. But the odds against finding such a result among a randomly chosen group of twelve Americans are actually more than a million to one. Are any of the dozen a graduate of Harvard, Stanford, Yale, Princeton, Cal Tech, MIT, Duke, Dartmouth, Cornell, Columbia, University of Chicago, or Brown? The chance that even one is a graduate of those twelve schools is one in a thousand. The chance of finding two among that group is one in fifty thousand. The chance of finding four or more is less than one in a billion.

Most readers of this book—this may be said because we know a great deal about the statistical tendencies of people who read a book like this—are in preposterously unlikely groups, and this reflects the degree of partitioning that has already occurred.

In some respects, the results of the exercise today are not so different from the results that would have been obtained in former years. Sixty years ago as now, the people who were most likely to read a book of this nature would be skewed toward those who had friends with college or Ivy League college educations and advanced degrees. The differences between 1930 and 1990 are these:

First, only a small portion of the 1930 population was in a position to have the kind of circle of friends and colleagues that characterizes the readers of this book. We will not try to estimate the proportion, which would involve too many assumptions, but you may get an idea by examining the small area under the curve for college graduates in the 1930 figure, and visualize some fraction of that area as representing people in 1930 who could conceivably have had the educational circle of friends and colleagues you have. They constituted the thinnest cream floating on the surface of American society in 1930. In 1990, they constituted a class.

Second, the people who obtained such educations changed. Suppose that it is 1930 and you are one of the small number of people whose circle

of twelve friends and colleagues included a sizable fraction of college graduates. Suppose you are one of the even tinier number whose circle came primarily from the top universities. Your circle, selective and uncommon as it is, nonetheless will have been scattered across a wide range of intelligence, with IQs from 100 on up. Given the same educational profile in one’s circle today, it would consist of a set of people with IQs where the bottom tenth is likely to be in the vicinity of 120, and the mean is likely to be in excess of 130—people whose cognitive ability puts them out at the edge of the population at large. What might have been a circle with education or social class as its most salient feature in 1930 has become a circle circumscribing a narrow range of high IQ scores today.

The sword cuts both ways. Although they are not likely to be among our readers, the circles at the bottom of the educational scale comprise lower and narrower ranges of IQ today than they did in 1930. When many youngsters in the top 25 percent of the intelligence distribution who formerly would have stopped school in or immediately after high school go to college instead, the proportion of high-school-only persons whose intelligence is in the top 25 percent of the distribution has to fall correspondingly. The occupational effect of this change is that bright youngsters who formerly would have become carpenters or truck drivers or postal clerks go to college instead, thence to occupations higher on the socioeconomic ladder. Those left on the lower rungs are therefore likely to be lower and more homogeneous intellectually. Likewise their neighborhoods, which get drained of the bright and no longer poor, have become more homogeneously populated by a less bright, and even poorer, residuum. In other chapters we focus on what is happening at the bottom of the distribution of intelligence.

The point of the exercise in thinking about your dozen closest friends and colleagues is to encourage you to detach yourself momentarily from the way the world looks to you from day to day and contemplate how extraordinarily different your circle of friends and acquaintances is from what would be the norm in a perfectly fluid society. This profound isolation from other parts of the IQ distribution probably dulls our awareness of how unrepresentative our circle actually is.

With these thoughts in mind, let us proceed to the technical answer to the question, How much partitioning is there in America? It is done by expressing the overlap of two distributions after they are equated for size. There are various ways to measure overlap. In the following table

we use a measure called

median overlap,

which says what proportion of IQ scores in the lower-scoring group matched or exceeded the median score in the higher-scoring group. For the nationally representative NLSY sample, most of whom attended college in the late 1970s and through the 1980s, the median overlap is as follows: By this measure, there is only about 7 percent overlap between people with only a high school diploma and people with a B.A. or M.A. And even this small degree of overlap refers to all colleges. If you went to any of the top hundred colleges and universities in the country, the measure of overlap would be a few percentage points. If you went to an elite school, the overlap would approach zero.

| Overlap Across the Educational Partitions | |

|---|---|

| Groups Being Compared | Median Overlap |

| High school graduates with college graduates | 7% |

| High school graduates with Ph.D.s, M.D.s, or LL.B.s | 1% |

| College graduates with Ph.D.s, M.D.s, and LL.Bs | 21% |

Even among college graduates, the partitions are high. Only 21 percent of those with just a B.A. or a B.S. had scores as high as the median for those with advanced graduate degrees. Once again, these degrees of overlap are for graduates of all colleges. The overlap between the B.A. from a state teachers’ college and an MIT Ph.D. can be no more than a few percentage points.

What difference does it make? The answer to that question will unfold over the course of the book. Many of the answers involve the ways that the social fabric in the middle class and working class is altered when the most talented children of those families are so efficiently extracted to live in other worlds. But for the time being, we can begin by thinking about that thin layer of students of the highest cognitive ability who are being funneled through rarefied college environments, whence they go forth to acquire eventually not just the good life but often an influence on the life of the nation. They are coming of age in environments that are utterly atypical of the nation as a whole. The national percentage of 18-year-olds with the ability to get a score of 700 or above on the SAT-Verbal test is in the vicinity of one in three hundred. Think about the consequences when about half of these students are going to universities in which 17 percent of their classmates also had

SAT-Vs in the 700s and another 48 percent had scores in the 600s.

35

It is difficult to exaggerate how different the elite college population is from the population at large—first in its level of intellectual talent, and correlatively in its outlook on society, politics, ethics, religion, and all the other domains in which intellectuals, especially intellectuals concentrated into communities, tend to develop their own conventional wisdoms.

The news about education is heartening and frightening, more or less in equal measure. Heartening, because the nation is providing a college education for a high proportion of those who could profit from it. Among those who graduate from high school, just about all the bright youngsters now get a crack at a college education. Heartening also because our most elite colleges have opened their doors wide for youngsters of outstanding promise. But frightening too. When people live in encapsulated worlds, it becomes difficult for them, even with the best of intentions, to grasp the realities of worlds with which they have little experience but over which they also have great influence, both public and private. Many of those promising undergraduates are never going to live in a community where they will be disabused of their misperceptions, for after education comes another sorting mechanism, occupations, and many of the holes that are still left in the cognitive partitions begin to get sealed. We now turn to that story.

Cognitive Partitioning by Occupation

People in different jobs have different average IQs. Lawyers, for example, have higher IQs on the average than bus drivers. Whether they

must

have higher IQs than bus drivers is a topic we take up in detail in the next chapter. Here we start by noting simply that people from different ranges on the IQ scale end up in different jobs.

Whatever the reason for the link between IQ and occupation, it goes deep. If you want to guess an adult male’s job status, the results of his childhood IQ test help you as much as knowing how many years he went to school.

IQ becomes more important as the job gets intellectually tougher. To be able to dig a ditch, you need a strong back but not necessarily a high IQ score. To be a master carpenter, you need some higher degree of intelligence along with skill with your hands. To be a first-rate lawyer, you had better come from the upper end of the cognitive ability distribution. The same may be said of a handful of other occupations, such as accountants, engineers and architects, college teachers, dentists and physicians, mathematicians, and scientists. The mean IQ of people entering those fields is in the neighborhood of 120. In 1900, only one out of twenty people in the top 10 percent in intelligence were in any of these occupations, a figure that did not change much through 1940. But after 1940, more and more people with high IQs flowed into those jobs, and by 1990 the same handful of occupations employed about 25 percent of all the people in the top tenth of intelligence.

During the same period, IQ became more important for business executives. In 1900, the CEO of a large company was likely to be a WASP born into affluence. He may have been bright, but that was not mainly how he was chosen. Much was still the same as late as 1950. The next three decades saw a great social leveling, as the executive suites filled with bright people who could maximize corporate profits, and never mind if they came from the wrong side

of the tracks or worshipped at a temple instead of a church. Meanwhile, the college degree became a requirement for many business positions, and graduate education went from a rarity to a commonplace among senior executives.