The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (13 page)

Read The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life Online

Authors: Richard J. Herrnstein,Charles A. Murray

Tags: #History, #Science, #General, #Psychology, #Sociology, #Genetics & Genomics, #Life Sciences, #Social Science, #Educational Psychology, #Intelligence Levels - United States, #Nature and Nurture, #United States, #Education, #Political Science, #Intelligence Levels - Social Aspects - United States, #Intellect, #Intelligence Levels

One source of circumstantial evidence that ties success in major business to intelligence is the past and present level of education of business executives.

19

In 1900, more than two-thirds of the presidents and chairmen of America’s largest corporations did not have even a college degree—not because many of them were poor (few had risen from out-right

poverty) but because a college degree was not considered important for running a business.

20

A Wall Street tycoon (himself a Harvard alumnus) writing in 1908 advised parents that “practical business is the best school and college” for their sons who sought a business career and that, indeed, a college education “is in many instances not only a hindrance, but absolutely fatal to success.”

21

The lack of a college education does not mean that senior executives of 1900 were necessarily less bright than their counterparts in 1990. But other evidence points to a revolution in the recruitment of senior executives that was not much different from the revolution in educational stratification that began in the 1950s. In 1900, the CEO of a large company was likely to be the archetype of the privileged capitalist elite that C. Wright Mills described in

The Power Elite:

born into affluence, the son of a business executive or a professional person, not only a WASP but an Episcopalian WASP.

22

In 1950, it was much the same. The fathers’ occupations were about the same as they had been in 1900, with over 70 percent having been business executives or professionals, and, while Protestantism was less overwhelmingly dominant than it had been in 1900, it remained the right religion, with Episcopalianism still being the rightest of all. Fewer CEOs in 1950 had been born into wealthy families (down from almost half in 1900 to about a third), but they were continuing to be drawn primarily from the economically comfortable part of the population. The proportion coming from poor families had not changed. Many CEOs in the first half of the century had their jobs because their family’s name was on the sign above the factory door; many had reached their eminent positions only because they did not have to compete against more able people who were excluded from the competition for lack of the right religion, skin color, national origin, or family connections.

In the next twenty-five years, the picture changed. The proportion of CEOs who came from wealthy families had dropped from almost half in 1900 and a third in 1950 to 5.5 percent by 1976.

23

The CEO of 1976 was still disproportionately likely to be Episcopalian but much less so than in 1900—and by 1976 he was also disproportionately likely to be Jewish, unheard of in 1920 or earlier. In short, social and economic background was no longer nearly as important in 1976 as in the first half of the century. Educational level was becoming the high road to the executive suite at the same time that education was becoming more dependent

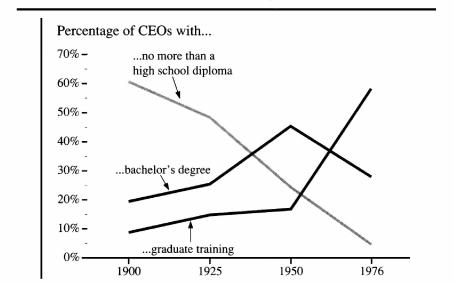

on cognitive ability, as Chapter 1 showed. The figure above traces the change in highest educational attainment from 1900 to 1976 for CEOs of the largest U.S. companies.

In fifty years, the education of the typical CEO increases from high school to graduate school

Source:

Burck 1976, p. 172; Newcomer 1955, Table 24.

The timing of the changes is instructive. The decline of the high school-educated chief executive was fairly steady throughout the period. College-educated CEOs surged into the executive suite in the 1925-1950 period. But as in the case of educational stratification, the most dramatic shift occurred after 1950, represented by the skyrocketing proportion of chief executives who had attended graduate school.

24

By 1976, 40 percent of the Fortune 500 companies were headed by individuals whose background was in finance or law, fields of study that are highly screened for intelligence. So we are left with this conservative interpretation: Nobody knows what the IQ mean or distribution was for executives at the turn of the century, but it is clear that, as of the 1990s, the cognitive screens were up. How far up? The broad envelope of possibilities suggests that senior business executives soak up a large proportion of the top IQ decile who are not engaged in the dozen

high-IQ professions. The constraints leave no other possibility. Here are the constraints and the arithmetic:

In 1990, the resident population ages 25 to 64 (the age group in which the vast majority of people working in high-IQ professions fall) consisted of 127 million people.

25

By definition, the top IQ decile thus consisted of 12.7 million people. The labor force of persons aged 25 to 64 consisted of 100 million people. The smartest working-age people are disproportionately likely to be in the labor force (especially since career opportunities have opened up for women). As a working assumption, suppose that the labor force of 100 million included 11 million of the 12.7 million people in the top IQ decile.

We already know that 7.3 million people worked in the high-IQ professions that year and have reason to believe that about half of those (3.65 million) have IQs of 120 or more. Subtracting 3.65 million from 11 million leaves us with about 7.4 million people in the labor force with IQs of 120 or more unaccounted for. Meanwhile, 12.9 million people were classified in 1980 as working in executive, administrative, and managerial positions.

26

A high proportion of people in those positions graduated from college, one screen. They have risen in the corporate hierarchy over the course of their careers, which is probably another screen for IQ. What is their mean IQ? There is no precise answer. Studies suggest that the mean for the job category including all white-collar and professionals is around 107, but that category is far broader than the one we have in mind. Moreover, the mean IQ of four-year college graduates in general was estimated at about 115 in 1972, and senior executives probably have a mean above that average.

27

At this point, we are left with startlingly little room for maneuver. How many of those 12.9 million people in executive, administrative, and managerial positions have IQs above 120? Any plausible assumption digs deep into the 7.4 million people with IQs of 120 or more who are not already engaged in one of the other high-IQ professions and leaves us with an extremely high proportion of people of the labor force with IQs above 120 who are already working in a high-IQ profession or in an executive or managerial position. One could easily make a case that the figure is in the neighborhood of 70 to 80 percent.

Cognitive sorting has become highly efficient in the last half century, but has it really become

that

efficient? We cannot answer definitely yes, but it is difficult to work back through the logic and come up with good reasons for thinking that the estimates are far off the mark.

It is not profitable to push much further along this line because the uncertainties become too great, but the main point is solidly established in any case: In midcentury, America was still a society in which a large proportion of the top tenth of IQ, probably a majority, were scattered throughout the population,

not

working in a high-IQ profession and

not

in a managerial position. As the century draws to a close, some very high proportion of that same group is concentrated within those highly screened jobs.

The Economic Pressure to Partition

What accounts for the way that people with different levels of IQ end up in different occupations? The fashionable explanation has been education. People with high SAT scores get into the best colleges; people with the high GRE, MCAT, or LSAT test scores get into professional and graduate schools; and the education defines the occupation. The SAT score becomes unimportant once the youngster has gotten into the right college or graduate school.

Without doubt, education is part of the explanation; physicians need a high IQ to get into medical school, but they also need to learn the material that medical school teaches before they can be physicians. Plenty of hollow credentialing goes on as well, if not in medicine then in other occupations, as the educational degree becomes a ticket for jobs that could be done just as well by people without the degree.

But the relationship of cognitive ability to job performance goes beyond that. A smarter employee is, on the average, a more proficient employee. This holds true within professions: Lawyers with higher IQs are, on the average, more productive than lawyers with lower IQs. It holds true for skilled blue-collar jobs: Carpenters with high IQs are also (on average) more productive than carpenters with lower IQs. The relationship holds, although weakly, even among people in unskilled manual jobs.

The magnitude of the relationship between cognitive ability and job performance is greater than once thought. A flood of new analyses during the 1980s established several points with large economic and policy implications:

Test scores predict job performance because they measure g, Spearman’s general intelligence factor, not because they identify “aptitude” for a specific job. Any broad test of general intelligence predicts proficiency in most common occupations, and does so more accurately than tests that are narrowly constructed around the job’s specific tasks.

The advantage conferred by IQ is long-lasting. Much remains to be learned, but usually the smarter employee tends to remain more productive than the less smart employee even after years on the job.

An IQ score is a better predictor of job productivity than a job interview, reference checks, or college transcript.

Most sweepingly important, an employer that is free to pick among applicants can realize large economic gains from hiring those with the highest IQs. An economy that lets employers pick applicants with the highest IQs is a significantly more efficient economy. Herein lies the policy problem: Since 1971, Congress and the Supreme Court have effectively forbidden American employers from hiring based on intelligence tests. How much does this policy cost the economy? Calculating the answer is complex, so estimates vary widely, from what one authority thinks was a lower-bound estimate of $80 billion in 1980 to what another authority called an upper-bound estimate of $13 billion for that year.

Our main point has nothing to do with deciding how large the loss is or how large the gain would be if intelligence tests could be freely used for hiring. Rather, it is simply that intelligence itself is importantly related to job performance. Laws can make the economy less efficient by forbidding employers to use intelligence tests, but laws cannot make intelligence unimportant.

T

o this point in the discussion, the forces that sort people into jobs according to their cognitive ability remain ambiguous. There are three main possibilities, hinted at in the previous chapter but not assessed.

The first is the standard one: IQ really reflects education. Education imparts skills and knowledge—reading, writing, doing arithmetic, knowing some facts. The skills and knowledge are valuable in the workplace, so employers prefer to hire educated people. Perhaps IQ, in and of itself, has something to do with people’s performance at work, but probably not much. Education itself is the key. More is better, for just about everybody, to just about any level.

The second possibility is that IQ is correlated with job status because we live in a world of artificial credentials. The artisan guilds of old were replaced somewhere along the way by college or graduate degrees. Most parents want to see their children get at least as much education as

they got, in part because they want their children to profit from the valuable credentials. As the society becomes richer, more children get more education. As it happens, education screens for IQ, but that is largely incidental to job performance. The job market, in turn, screens for educational credentials. So cognitive stratification occurs in the workplace, but it reflects the premium put on education, not on anything inherent in either education or cognitive ability itself.

The third possibility is that cognitive ability itself—sheer intellectual horsepower, independent of education—has market value. Seen from this perspective, the college degree is not a credential but an indirect measure of intelligence. People with college degrees tend to be smarter than people without them and, by extension, more valuable in the marketplace. Employers recruit at Stanford or Yale not because graduates of those schools know more than graduates of less prestigious schools but for the same generic reason that Willie Sutton gave for robbing banks. Places like Stanford and Yale are where you find the coin of cognitive talent.

The first two explanations have some validity for some occupations. Even the brightest child needs formal education, and some jobs require many years of advanced training. The problem of credentialing is widespread and real: the B. A. is a bogus requirement for many management jobs, the requirement for teaching certificates often impedes hiring good teachers in elementary and secondary schools, and the Ph.D. is irrelevant to the work that many Ph.D.s really do.