The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (152 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

The looseness of the connection between resource control and violence should also come as no surprise. Evolutionary psychologists tell us that no matter how rich or poor men are, they can always fight over women, status, and dominance. Economists tell us that wealth originates not from land with stuff in it but from the mobilization of ingenuity, effort, and cooperation to turn that stuff into usable products. When people divide the labor and exchange its fruits, wealth can grow and everyone wins. That means that resource competition is not a constant of nature but is endogenous to the web of societal forces that includes violence. Depending on their infrastructure and mindset, people in different times and places can choose to engage in positive-sum exchanges of finished products or in zero-sum contests over raw materials—indeed, negative-sum contests, because the costs of war have to be subtracted from the value of the plundered materials. The United States could invade Canada to seize its shipping lane to the Great Lakes or its precious deposits of nickel, but what would be the point, when it already enjoys their benefits through trade?

Affluence.

Over the millennia, the world has become more prosperous, and it has also become less violent. Do societies become more peaceful as they get richer? Perhaps the daily pains and frustrations of poverty make people more ornery and give them more to fight over, and the bounty of an affluent society gives them more reasons to value their lives, and by extension, the lives of others.

Over the millennia, the world has become more prosperous, and it has also become less violent. Do societies become more peaceful as they get richer? Perhaps the daily pains and frustrations of poverty make people more ornery and give them more to fight over, and the bounty of an affluent society gives them more reasons to value their lives, and by extension, the lives of others.

Nonetheless tight correlations between affluence and nonviolence are hard to find, and some correlations go the other way. Among pre-state peoples, it is often the sedentary tribes living in temperate regions flush with fish and game, such as the Pacific Northwest, that had slaves, castes, and a warrior culture, while the materially modest San and Semai are at the peaceable end of the distribution (chapter 2). And it was the glorious ancient empires that had slaves, crucifixions, gladiators, ruthless conquest, and human sacrifice (chapter 1).

The ideas behind democracy and other humanitarian reforms blossomed in the 18th century, but upsurges in material well-being came considerably later (chapter 4). Wealth in the West began to surge only with the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century, and health and longevity took off with the public health revolution at the end of the 19th. Smaller-scale fluctuations in prosperity also appear to be out of sync with a concern for human rights. Though it has been suggested that lynchings in the American South went up when cotton prices went down, the overwhelming historical trend was an exponential decay of lynchings in the first half of the 20th century, without a deflection in either the Roaring Twenties or the Great Depression (chapter 7). As far as we can tell, the Rights Revolutions that started in the late 1950s did not pick up steam or run out of it in tandem with the ups and downs of the business cycle. And they are not automatic outcomes of modern affluence, as we see in the relatively high tolerance of domestic violence and the spanking of children in some well-to-do Asian states (chapter 7).

Nor does violent crime closely track the economic indicators. The careenings of the American homicide rate in the 20th century were largely uncorrelated with measures of prosperity: the murder rate plunged in the midst of the Great Depression, soared during the boom years of the 1960s, and hugged new lows during the Great Recession that began in 2007 (chapter 3). The poor correlation could have been predicted by the police blotters, which show that homicides are driven by moralistic motives like payback for insults and infidelity rather than by material motives such as cash or food.

Wealth and violence do show a powerful connection in one comparison: differences among countries at the bottom of the economic scale (chapter 6). The likelihood that a country will be torn by violent civil unrest, as we saw, starts to soar as its annual per capita domestic product falls below $1,000. It’s hard, though, to pinpoint the causes behind the correlation. Money can buy many things, and it’s not obvious which of the things that a country cannot afford is responsible for its violence. It may be deprivations of individual people, such as nutrition and health care, but it also may be deprivations of the entire country, such as decent schools, police, and governments (chapter 6). And since war is development in reverse, we cannot even know the degree to which poverty causes war or war causes poverty.

And though extreme poverty is related to civil war, it does not seem to be related to genocide. Recall that poor countries have more political crises, and political crises can lead to genocides, but once a country has a crisis, poverty makes it no more likely to host a genocide (chapter 6). At the other end of the affluence scale, late 1930s Germany had the worst of the Great Depression behind it and was becoming an industrial powerhouse, yet that was when it brewed the atrocities that led to the coining of the word

genocide

.

genocide

.

The tangled relationship between wealth and violence reminds us that humans do not live by bread alone. We are believing, moralizing animals, and a lot of our violence comes from destructive ideologies rather than not enough wealth. For better or worse—usually worse—people are often willing to trade off material comfort for what they see as spiritual purity, communal glory, or perfect justice.

Religion.

Speaking of ideologies, we have seen that little good has come from ancient tribal dogmas. All over the world, belief in the supernatural has authorized the sacrifice of people to propitiate bloodthirsty gods, and the murder of witches for their malevolent powers (chapter 4). The scriptures present a God who delights in genocide, rape, slavery, and the execution of nonconformists, and for millennia those writings were used to rationalize the massacre of infidels, the ownership of women, the beating of children, dominion over animals, and the persecution of heretics and homosexuals (chapters 1, 4, and 7). Humanitarian reforms such as the elimination of cruel punishment, the dissemination of empathy-inducing novels, and the abolition of slavery were met with fierce opposition in their time by ecclesiastical authorities and their apologists (chapter 4). The elevation of parochial values to the realm of the sacred is a license to dismiss other people’s interests, and an imperative to reject the possibility of compromise (chapter 9). It inflamed the combatants in the European Wars of Religion, the second-bloodiest period in modern Western history, and it continues to inflame partisans in the Middle East and parts of the Islamic world today. The theory that religion is a force for peace, often heard among the religious right and its allies today, does not fit the facts of history.

Speaking of ideologies, we have seen that little good has come from ancient tribal dogmas. All over the world, belief in the supernatural has authorized the sacrifice of people to propitiate bloodthirsty gods, and the murder of witches for their malevolent powers (chapter 4). The scriptures present a God who delights in genocide, rape, slavery, and the execution of nonconformists, and for millennia those writings were used to rationalize the massacre of infidels, the ownership of women, the beating of children, dominion over animals, and the persecution of heretics and homosexuals (chapters 1, 4, and 7). Humanitarian reforms such as the elimination of cruel punishment, the dissemination of empathy-inducing novels, and the abolition of slavery were met with fierce opposition in their time by ecclesiastical authorities and their apologists (chapter 4). The elevation of parochial values to the realm of the sacred is a license to dismiss other people’s interests, and an imperative to reject the possibility of compromise (chapter 9). It inflamed the combatants in the European Wars of Religion, the second-bloodiest period in modern Western history, and it continues to inflame partisans in the Middle East and parts of the Islamic world today. The theory that religion is a force for peace, often heard among the religious right and its allies today, does not fit the facts of history.

Defenders of religion claim that the two genocidal ideologies of the 20th century, fascism and communism, were atheistic. But the first claim is mistaken and the second irrelevant (chapter 4). Fascism happily coexisted with Catholicism in Spain, Italy, Portugal, and Croatia, and though Hitler had little use for Christianity, he was by no means an atheist, and professed that he was carrying out a divine plan.

1

Historians have documented that many of the Nazi elite melded Nazism with German Christianity in a syncretic faith, drawing on its millennial visions and its long history of anti-Semitism.

2

Many Christian clerics and their flocks were all too happy to sign up, finding common cause with the Nazis in their opposition to the tolerant, secular, cosmopolitan culture of the Weimar era.

3

1

Historians have documented that many of the Nazi elite melded Nazism with German Christianity in a syncretic faith, drawing on its millennial visions and its long history of anti-Semitism.

2

Many Christian clerics and their flocks were all too happy to sign up, finding common cause with the Nazis in their opposition to the tolerant, secular, cosmopolitan culture of the Weimar era.

3

As for godless communism, godless it certainly was. But the repudiation of one illiberal ideology does not automatically grant immunity from others. Marxism, as Daniel Chirot observed (see page 330), helped itself to the worst idea in the Christian Bible, a millennial cataclysm that will bring about a utopia and restore prelapsarian innocence. And it violently rejected the humanism and liberalism of the Enlightenment, which placed the autonomy and flourishing of individuals as the ultimate goal of political systems.

4

4

At the same time,

particular

religious movements at particular times in history

have

worked against violence. In zones of anarchy, religious institutions have sometimes served as a civilizing force, and since many of them claim to hold the morality franchise in their communities, they can be staging grounds for reflection and moral action. The Quakers parlayed Enlightenment arguments against slavery and war into effective movements for abolition and pacifism, and in the 19th century other liberal Protestant denominations joined them (chapter 4). Protestant churches also helped to tame the wild frontier of the American South and West (chapter 3). African American churches supplied organizational infrastructure and rhetorical power to the civil rights movement (though as we saw, Martin Luther King rejected mainstream Christian theology and drew his inspiration from Gandhi, secular Western philosophy, and renegade humanistic theologians). These churches also worked with the police and community organizations to lower crime in African American inner cities in the 1990s (chapter 3). In the developing world, Desmond Tutu and other church leaders worked with politicians and nongovernmental organizations in the reconciliation movements that healed countries following apartheid and civil unrest (chapter 8).

particular

religious movements at particular times in history

have

worked against violence. In zones of anarchy, religious institutions have sometimes served as a civilizing force, and since many of them claim to hold the morality franchise in their communities, they can be staging grounds for reflection and moral action. The Quakers parlayed Enlightenment arguments against slavery and war into effective movements for abolition and pacifism, and in the 19th century other liberal Protestant denominations joined them (chapter 4). Protestant churches also helped to tame the wild frontier of the American South and West (chapter 3). African American churches supplied organizational infrastructure and rhetorical power to the civil rights movement (though as we saw, Martin Luther King rejected mainstream Christian theology and drew his inspiration from Gandhi, secular Western philosophy, and renegade humanistic theologians). These churches also worked with the police and community organizations to lower crime in African American inner cities in the 1990s (chapter 3). In the developing world, Desmond Tutu and other church leaders worked with politicians and nongovernmental organizations in the reconciliation movements that healed countries following apartheid and civil unrest (chapter 8).

So the subtitle of Christopher Hitchens’s atheist bestseller,

How Religion Poisons Everything

, is an overstatement. Religion plays no single role in the history of violence because religion has not been a single force in the history of anything. The vast set of movements we call religions have little in common but their distinctness from the secular institutions that are recent appearances on the human stage. And the beliefs and practices of religions, despite their claims to divine provenance, are endogenous to human affairs, responding to their intellectual and social currents. When the currents move in enlightened directions, religions often adapt to them, most obviously in the discreet neglect of the bloodthirsty passages of the Old Testament. Not all of the accommodations are as naked as those of the Mormon church, whose leaders had a revelation from Jesus Christ in 1890 that the church should cease polygamy (around the time that polygamy was standing in the way of Utah’s joining the Union), and another one in 1978 telling them that the priesthood should accept black men, who were previously deemed to bear the mark of Cain. But subtler accommodations instigated by breakaway denominations, reform movements, ecumenical councils, and other liberalizing forces have allowed other religions to be swept along by the humanistic tide. It is when fundamentalist forces stand athwart those currents and impose tribal, authoritarian, and puritanical constraints that religion becomes a force for violence.

THE PACIFIST’S DILEMMAHow Religion Poisons Everything

, is an overstatement. Religion plays no single role in the history of violence because religion has not been a single force in the history of anything. The vast set of movements we call religions have little in common but their distinctness from the secular institutions that are recent appearances on the human stage. And the beliefs and practices of religions, despite their claims to divine provenance, are endogenous to human affairs, responding to their intellectual and social currents. When the currents move in enlightened directions, religions often adapt to them, most obviously in the discreet neglect of the bloodthirsty passages of the Old Testament. Not all of the accommodations are as naked as those of the Mormon church, whose leaders had a revelation from Jesus Christ in 1890 that the church should cease polygamy (around the time that polygamy was standing in the way of Utah’s joining the Union), and another one in 1978 telling them that the priesthood should accept black men, who were previously deemed to bear the mark of Cain. But subtler accommodations instigated by breakaway denominations, reform movements, ecumenical councils, and other liberalizing forces have allowed other religions to be swept along by the humanistic tide. It is when fundamentalist forces stand athwart those currents and impose tribal, authoritarian, and puritanical constraints that religion becomes a force for violence.

Let me turn from the historical forces that don’t seem to be consistent reducers of violence to those that do. And let me try to place these forces into a semblance of an explanatory framework so that, rather than ticking off items on a list, we can gain insight into what they might have in common. What we seek is an understanding of why violence has always been so tempting, why people have always yearned to reduce it, why it has been so hard to reduce, and why certain kinds of changes eventually did reduce it. To be genuine explanations, these changes should be exogenous: they should not be a part of the very decline we are trying to explain, but independent developments that preceded and caused it.

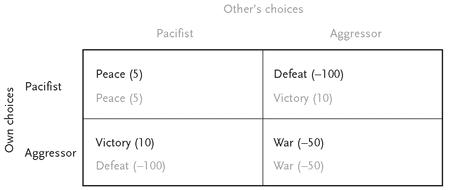

A good way to make sense of the changing dynamics of violence is to think back to the paradigmatic model of the benefits of cooperation (in this case, refraining from aggression), namely the Prisoner’s Dilemma (chapter 8). Let’s change the labels and call it the Pacifist’s Dilemma. A person or coalition may be tempted by the gains of a victory in predatory aggression (the equivalent of defecting against a cooperator), and certainly wants to avoid the sucker’s payoff of being defeated by an adversary who acts on the same temptation. But if they both opt for aggression, they will fall into a punishing war (mutual defection), which will leave them both worse off than if they had opted for the rewards of peace (mutual cooperation). Figure 10–1 is a depiction of the Pacifist’s Dilemma; the numbers for the gains and losses are arbitrary, but they capture the dilemma’s tragic structure.

FIGURE 10–1.

The Pacifist’s Dilemma

The Pacifist’s Dilemma

The Pacifist’s Dilemma is by no stretch of the imagination a mathematical model, but I will keep pointing to it to offer a second way of conveying the ideas I will try to explain in words. The numbers capture the twofold tragedy of violence. The first part of the tragedy is that when the world has these payoffs, it is irrational to be a pacifist. If your adversary is a pacifist, you are tempted to exploit his vulnerability (the 10 points of victory are better than the 5 points of peace), whereas if he is an aggressor, you are better off enduring the punishment of a war (a loss of 50 points) than being a sucker and letting him exploit you (a devastating loss of 100). Either way, aggression is the rational choice.

Other books

Carolina Girl by Virginia Kantra

Llamada para el muerto by John Le Carré

Little Shop of Homicide by Denise Swanson

Close to Her Heart by C. J. Carmichael

Passage West by Ruth Ryan Langan

Versed in Desire by Anne Calhoun

Cool Heat by Watkins, Richter

Master Mage by D.W. Jackson

City of Shadows by Pippa DaCosta

Domestic Enemies: The Reconquista by Matthew Bracken