The Body Economic (21 page)

Authors: David Stuckler Sanjay Basu

Long before the Great Recession, Swedish policymakers had been acting as doctors to the masses. The country's innovative social protection plan is called the Active Labor Market Program (ALMP). “Active” is the crucial word here. ALMPs are different from typical social safety nets for the unemployed more commonly found in countries such as the US, Spain, and the UK. Those “passive” programs usually provide cash benefits to the unemployed to replace their lost income (of course, the recipients had contributed every month to their unemployment insurance while they were working). While there is little doubt that unemployment checks help unemployed people to continue to support their families and make ends meet, the Swedes designed their programs to be “activating”âto help people get back into new jobs as quickly as possible.

15

Since the 1960s, Sweden had been developing ALMP programs that provide workers with support, skills, and a plan to get back to work. While there is a lot of variation in how countries organize their ALMPs, Sweden's were particularly well-developed and comprehensive to help keep workers active. In Sweden, when people lose their jobs, both they and their firms register at a government job center. So people participate by default. Within the next thirty days, the center creates an “individual action plan” with the person who has become unemployed. This individual has an interview with a job trainer every six weeks to see how the job search is going. The program also requires that the participant continue their job search (and it verifies their efforts) during their participation in the ALMP. In order for people to access cash benefits, they have to take part in a guided, step-by-step plan to get back into work.

Sweden's ALMPs placed a much greater emphasis on activating workers than the US or Spain. The unemployed in Sweden were not just having their hands held, but were being actively reached out in order to help them stay

economically active, and program managers worked with companies to get new jobs generated for their recently laid-off workers. That is not to say that unemployment offices in the US and Spain didn't provide job search opportunitiesâthey did, but their programs were far less active in their out-reach and aims than the Swedish ALMPs. One of Sanjay's patients, for example, encountered a US version of an “ALMP”; he had to wait three hours to get a pamphlet that told him to prepare a resumé, take a shower, and wear a suit.

Before the Great Recession, ALMPs had played a critical role in preventing unemployment from causing depression in those countries that deployed them. In Finland, a randomized controlled trial in 2002 tested the effectiveness of the country's ALMP program, Työhön (meaning “let's go to work”). Researchers assigned 629 people who had lost their jobs to a job-training program with skilled caseworkers. A control group of 632 people received printed information about finding a job (the same printed information provided by the ALMP program) but did not receive the actual help of a Työhön trainer. The results were remarkably different between the two groups. Within three months, the researchers found, workers who were enrolled in the Työhön program experienced significantly fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety, with the greatest benefits seen in those previously at high risk of depression. The researchers found that two years later ALMP participants had significantly fewer depressive symptoms and higher self-esteem, were less likely to have given up hope on finding a job, and were more likely to have successfully returned to work than the control group.

16

In practice, ALMPs provided mental health resilience to job loss in at least three ways. First, they helped people who lost their jobs find new ones as soon as possibleâeliminating a key source of depression and anxiety. Indeed, studies of depression showed that symptoms of short-term depression often disappeared once an unemployed individual returned to work. Second, ALMPs helped reduce the mental health risks that accompanied job loss by providing formal social support through a trainer, as opposed to leaving people to cope with job loss on their own. Third, the data showed that these programs could even help people who were not unemployed but worried they might be; those at risk of losing their job knew they would get assistance to find a new one, and this appeared to prevent depressive symptoms among those at high risk for unemployment. If properly implemented,

ALMPs were a classic win-win situation: improving the economy and preventing depression.

17

Sweden had been learning from these data since the 1960s, and by the 1980s began operating some of the most highly sophisticated ALMPs in the world. One reason was that their politicians invested in well-resourced programs. Each year, Sweden spent a total of $580 per capita to help the unemployed get back into work. The US, UK, and Spain were spending less than half of this figure. Not only did Sweden invest more, but it invested proportionally more in active programs rather than passive paychecks. In the mid-1980s, Sweden spent about three-quarters of its funds to help the unemployed on active programs, whereas the US spent about one-third, the UK one-quarter, and Spain about one-tenth of their budgets on active programs. In 2005, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development published a comprehensive report comparing unemployment programs across European countries. It found that Sweden's investment was paying off: its ALMPs had among the quickest response times in setting up interviews and individual action plans for the newly unemployed.

18

These results all seemed well and good during normal economic times. But would these programs be enough to help protect Sweden from experiencing a large rise in suicides during an economic meltdown?

The protective effects of Sweden's ALMPs were put to the test during its recession in the 1990s. In a scenario that resembles the current recession, Sweden's housing market collapsed in 1991 and 1992, bringing nearly all of its 114 banks to near-closure. GDP fell by 12 percent. Ten percent of Swedish workers lost their jobsâa rise on par with unemployment spikes in many countries during the current recession.

19

Remarkably, despite Sweden's large spike in unemployment, suicide rates actually

fell

steadily during the period between the 1980s and 2000s, when the government invested, on average, about $360 per capita per year in active labor market programs (see

Figure 7.3

). There was no significant correlation between Sweden's fluctuations in unemployment and its suicide rates.

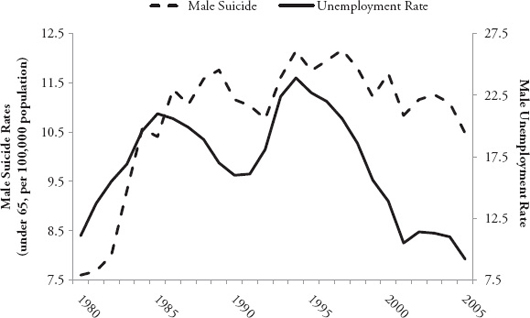

Like Sweden, Spain experienced large increases in unemployment from its recessions of the 1980s and 1990s. But Spain operated a relatively poorly resourced unemployment program, investing only about $90 capita per year, and focusing this money only on cash benefits. For men in Spain, trends in unemployment correlated strongly with suicide rates, as shown in

Figure 7.4

.

20

F

IGURE 7.3

Active Labor Market Programs, Unemployment, and Suicide in Swedish Men, 1980â2005

21

(solid line: unemployment; broken line: suicide)

We wanted to be as sure as possible that ALMPs were the determining factor in reducing the risk of suicide during economic recession. So we examined suicide rates and unemployment programs across all of the European countries using over two decades of data, comparing ALMPs to all the other main types of social protection programs, including healthcare services, family support such as childcare support, housing subsidies, old-age pensions, and passive unemployment benefits to see which, if any, could prevent an increase in suicide rates during recessions. Healthcare spending, for example, did not significantly reduce the risk of suicides from unemployment. This made sense: if the main risks of depression came from factors like unemployment, the formal healthcare system would probably not have much power to neutralize these risk factors. We also found that cash benefits didn't reduce the risk. In test after test, we found that the ALMPs had the greatest and most significant preventive effects on suicide when compared to other social protection programs.

We estimated that, if done properly, ALMPs could neutralize the suicide risk of a recession. In our findings, published in the peer-reviewed medical journal The

Lancet

, we estimated that for a $100 investment per capita, on

average ALMPs appeared to lower the risk of unemployment-related suicide from 1.2 percent to 0.4 percent.

F

IGURE 7.4

Active Labor Market Programs, Unemployment, and Suicide in Spanish Men, 1980â2005

22

(solid line: unemployment; broken line: suicide)

The data provided a striking example of how social protection programs could save lives. When countries invested more than about $200 per capita in ALMPs, the correlation of unemployment with suicides appeared to completely vanish. This was precisely why unemployment spikes had no correlation with increased suicides in Sweden, Finland, and Iceland, but unemployment was strongly correlated to suicide in Spain, the US, Greece, Italy, and Russia.

The lessons we learned from our research on ALMPs provided answers to several puzzles. First, ALMPs statistically explained why becoming unemployed was so much more dangerous for people in Eastern rather than Western Europe. At the time when the Soviet Union disintegrated, Finland, a major trading partner in Western Europe, suddenly lost one-third of its economy as the sales made to Soviet factories evaporated. Finland also had a drinking culture similar to the Soviet Union, and its unemployment had soared during the recession. Yet there was little or no discernible effect of the economic crash on suicides in the country. By contrast, the surge in unemployment in Russia, Kazakhstan, and the Baltic states corresponded to a devastating mortality crisis. This dramatic difference could be explained by the

fact that Western European countries like Finland tended to invest considerably more in labor market protections (about $150 per capita) than did Eastern European countries ($37 per capita).

23

When we presented our findings at research conferences, our colleagues in Russia and Poland suggested that unlike Sweden or Finland, their countries simply couldn't afford to invest in ALMPs. But we found that, if executed well (i.e., in the Swedish style), ALMPs would essentially pay for themselves by boosting employment and reducing the burden on social welfare. A detailed analysis of Danish ALMPs, for example, concluded that the economic benefits of these programs far exceeded their costs, because the programs increased workers' productivity and reduced reliance on welfare support. In Denmark, the programs generated a net savings of 279,000 Danish kroner (about $47,000) per worker over eleven years. Another study in 2010 performed a systematic review of 199 ALMPs studied in 97 research experiments. It found a similar consistent pattern of results as the Danish program: that ALMPs helped people return to work and, by keeping people economically active, reduced pressure on public welfare systems by increasing the economy's labor supplyâa main engine of economic growth.

With all of this evidence accumulating in favor of ALMPs, we were eager to translate these data into practice. After we published our research in 2009 about the benefits of ALMPs, we were invited to the British House of Commons and the Swedish Parliament to present our data and recommendations.

24

The responses were remarkableâthat is, remarkably dissimilarâin the two countries. When presented with the data that unemployment led to a rise in suicides, and that ALMPs could help mitigate the risks, the Swedish members of Parliament were unsurprised. One member asked: “Why are you telling us what we already know?” But when we presented the same data in the UK, in July 2009, to the House of Commons, the reaction was that the government was “already doing all it could to reduce unemployment.”