The Body Economic (20 page)

Authors: David Stuckler Sanjay Basu

Whether the British people will fully accept this radical privatization of their healthcare system remains unclear. But once market incentives take hold of a public system, it becomes difficult, if not impossible to reverse course. In the UK, the recession-fueled combination of austerity-and-privatization seems to be creeping into every dimension of the social protection system. But evidence of its harms should give us all pause.

27

The UK is not the only country to go down the path of healthcare privatization and cuts. Greece was perhaps the most extreme example of intentional and large cuts to healthcare, as the IMF targeted healthcare as a key budget area from which to save short-term costs. Spain had a National Health Service, similar to the British. But as its public health budgets were cut, it began to shift care to the private sector. Fees were added to basic services, so that people had to pay more out of pocketâdespite clear-cut evidence that these “user fees” reduced access to necessary care and didn't save money in the long-run.

28

Spain also redefined its eligibility criteria from “residents” to “citizens,” purging immigrants from the system as a means to save money. Medicines that were once included in insurance packages were carved out. And in other cases, they simply became unavailableâas in Valencia, Spain, where pharmacies stood empty after the central government cut their funding.

There is an alternativeâone that the UK itself had proven during its period of tremendous hardship and enormous debt after World War II. As Italy, Spain, and Greece, under pressure from the troika, are also now pursuing

radical privatization and austerity reforms to their National Health Services, they would do well to recall the words of the NHS founder, Aneurin Bevan, who back in 1948 put this moral question in ringingly simple terms: “We ought to take pride in the fact that, despite our financial and economic anxieties, we are still able to do the most civilized thing in the worldâput the welfare of the sick in front of every other consideration.”

29

RETURNING TO WORK

On May 4, 2012, a crowd of women waving white flags marched to the entrance of the Italian government's Equitalia tax office in Bologna. They were the

vedove bianche,

the White Widows. Following Italy's austerity drive in response to the Great Recession, their husbands hadn't been able to find enough work or pay their tax debts. And so the men had chosen to end it all by taking their lives. Saddled with debt, and left to pick up the pieces, the widows were angry and frustrated that the government wasn't helping them.

1

“Non ci suiciderete!”

they chanted: “Don't suicide us.” Tiziana Marrone, the leader of the protest, said, “The government must do something. It is not right what is happening in Italy.” They were upset that the government had turned a blind eye to tax evasion by Italy's super-rich, but done virtually nothing to support those who had lost everything in the Great Recession. She continued, “My battle is not just mine, it is of all the Italians who find themselves in my condition, and most of all of the widows of those families, who don't know where to turn to pay all these debts.”

2

It was the second protest at the Equitalia building. Five weeks earlier, on March 28, Giuseppe Campaniello, a self-employed bricklayer, and the husband of Tiziana Marrone, went to the same office. He had just received a final notice from Equitalia doubling a fine he reportedly couldn't pay. So in front of the tax offices, he doused himself with gasoline and set himself on

fire. He had left a note for Tiziana: “Dear love, I am here crying. This morning I left a bit early, I wanted to wake you, say goodbye, but you were sleeping so well I was afraid to wake you. Today is an ugly day. I ask forgiveness from everyone. A kiss to you all. I love you, Giuseppe.” He died nine days later.

In the Great Recession, suicide rates rose as unemployment rates jumped by 39 percent across Italy between 2007 and 2010. While the White Widows' protest drew public attention to their private suffering from the mental health consequences of unemployment in Italy, not everyone agreed with their interpretation of events. Some commentators said that Italy's economic suicides were just “normal fluctuations.”

3

To find out whether this was true and if so why, we looked into the country's mortality datasets. Italy has a uniquely detailed system for tracking each of its suicides. The death certificates include contextual details about the causes. One example was a certificate of a sixty-four-year-old bricklayer who had lost his job at Christmas. He left a note that said in part, “I can't live without a job,” then shot himself. In Italy, as in Russia during the early 1990s, unemployment had left people demoralized, hopeless, and ultimately prone to self-harm.

4

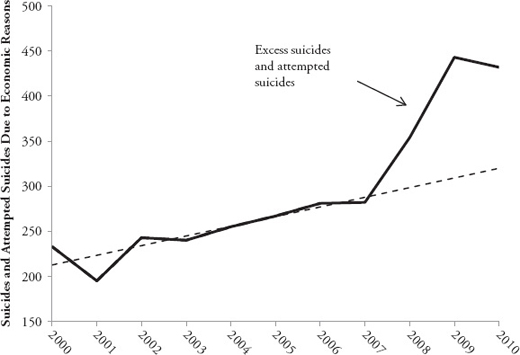

We found that there was a large rise in suicide death certificates labeled “due to economic reasons” during the recession, well above pre-existing trends. Notably, rates of suicides attributable to all other causes remained unchanged. Overall, we estimated that Italy suffered at least 500 new cases of suicide and attempted suicides beyond what would have been expected if pre-recession suicide trends had continued.

Figure 7.1

shows the jump in excess suicides and suicide attempts due to the combination of the Great Recession and the Italian government's austerity response.

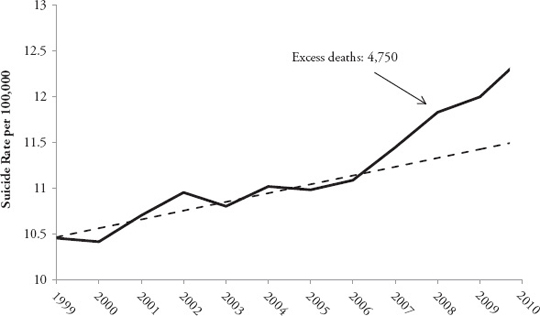

Across the Atlantic, the US suicide data were also on the rise during the recession. In the lead-up to the recession, suicides had already been increasing. For

Figure 7.2

, we projected the rate of suicides if those trends had continued, as shown in the dashed line. What we found is that the recession made a bad situation worse, as suicide deaths accelerated (

Figure 7.2

's solid line), rising by an additional 4,750 deaths during the recession over and above the pre-existing trend.

5

There was little doubt that the recession was a major cause of the increase in suicides. But it was neither a necessary cause, nor a sufficient cause of these

tragedies. In countries that weren't helping to buffer families against unemployment, suicides often correlated with job losses, as in Italy and the United States. But in other countries, politicians chose to invest in social programs that helped people return to work. Sweden and Finland experienced large recessions at various times during the 1980s and 1990s, but had no significant rise in suicides despite experiencing large spikes in unemployment. Sweden and Finland found ways to prevent a crashing economy from taking a toll on people's mental health. Unemployment may be a common shock during recessions, but increased rates of suicidality are not.

F

IGURE 7.1

Recession and Austerity Increase Italy's Economic Suicides and Suicide Attempts

6

Since the nineteenth century, it has been known that recessions and unemployment correlate with significantly greater risks of suicide. With advances in data collection, public health researchers and sociologists were able to establish that unemployment is a major risk factor for depression, anxiety, sleeplessness, and self-harm. Losing a job can tip a person into depression, especially in people who lack social support or are alone. People who are looking for work are about twice as likely to end their lives than those who have jobs.

7

F

IGURE 7.2

Recession Leads to an Increase in Suicides, United States

8

During the early 1980s, some British economists began to question this conventional wisdom, asking whether unemployment was actually causing mental health problems per se or whether instead those who lost jobs were more likely to have been depressed in the first place. It was only possible to address this important question with large studies that tracked people over time, enabling researchers to disentangle which came firstâjob loss or depression. The answer, it turned out, was both: some people became depressed because they lost their jobs, while some were more likely to lose their jobs because they already suffered from depression, and their depression worsened because of unemployment.

9

Hence, soon after the start of the Great Recession in 2007, doctors in Spain and the UK began to see a large rise in the number of patients coming to their clinics with acute depressive symptoms. As Peter Byrne, director of public education at the Royal College of Psychiatrists in the UK, said, “In 2009 all of usâwhether we work in general practice, general hospitals or specialist servicesâare seeing an increase in referrals from the recession. The stresses of the downturn are the last straw for many people.”

10

With more patients showing signs of depression, doctors began to prescribe more antidepressants. In the UK, antidepressant use rose 22 percent between 2007 and 2009. A survey in 2010 found that 7 percent of those seeking help for “work-related stress” began pharmacological treatment for

depression. Doctors gave out 3.1 million more antidepressant prescriptions in 2010 than they had just two years earlier.

11

Spain and the United States also saw rises in antidepressant prescriptions. Between 2007 and 2009, the number of people taking daily antidepressants jumped by 17 percent in Spain. In the United States, use of antidepressants rose during the Great Recession to where 10 percent of the adult population were prescribed antidepressants during the recession. A study by Bloomberg Rankings found that rates of antidepressant prescriptions had a very strong correlation with unemployment rates.

12

From a statistical perspective, these data demonstrated only that more people were seeking medication for depression during the Great Recession. They did not, in and of themselves, prove that unemployed people were uniquely affected. In theory, it is quite possible that people were simply more stressed and unhappy during the recession for other reasons: the general atmosphere of malaise, increased workloads, anxiety surrounding the possibility of being laid off, etc. These numbers alone did not prove that unemployment per se was the driver of worse depression in this recession.

13

We set out to study which people were showing up to doctors' offices with depression symptoms. We looked at data on 7,940 patients from doctors' offices across Spain before the recession (2006) and during it (2010). Spain continues to grapple with one of the largest global increases in unemployment during the recession, but also had kept good track of mental health through a series of standardized depression surveys. Those surveys revealed that the number of patients showing up at the doctor's office with clinical symptoms of major depression rose from 29 percent to 48 percent between 2006 and 2010. Minor depression rose from 6 percent to about 9 percent, reports of panic attacks went up from 10 percent to 16 percent, and even alcohol abuse rose from less than 1 percent to 6 percent. Recent unemployment was a key statistical predictor of these mental health problems. This remained the case after we controlled for a number of other possible factors, including preexisting depression and access to mental healthcare.

14

Of course, there are other ways to address the problem of unemployment than with antidepressants. As Dr. Geoffrey Rose, the father of preventive medicine, put it: “What good does it do to give a patient medicine but send them back to the environment that made them sick in the first place?” The real question that we, along with many other epidemiologists, are now trying

to understand is how we can prevent these problems from happening when large numbers of people lose work.

While millions of new prescriptions were being written in the US, UK, and Spain, not all countries facing big spikes in unemployment witnessed such large rises in the use of antidepressants. In Sweden, prescriptions rose by only 6 percent between 2007 and 2010, much less than the rise in Spain or in the UK. Instead of treating symptoms with pills alone, the Swedish response during the Great Recession, and earlier, was to address a root cause of depressionâunemployment itself.