The Book of Duels (10 page)

Authors: Michael Garriga

The Dragon, the Age of Man

B

y day I hide within the caves of Tripoli and I sleep in their shadows and folds, by night I fly through the sky or crawl over the land or swim far upon the water, and I am your greatest fears, human—you cannot reason with me or come to terms with me or soothe or coerce or mitigate me, not with all the rubies in the Turk’s great vault nor all the flesh of your doughy young virgins nor your roaming goats nor your shaky faith—to appease me you slaughter your own, kill one another to advance your claim over land and sea, or you bring me a wee child and chain her to the rocky outcrops and beg me take her, only her—and I will eat, human, because I must—I am the guardian of the sacred fire so the flames from my mouth are sacrificial, the same as the heat from your own bodies, which burn the sacrifice you take through your mouths—all things that live must die and be consumed, so the whole world is a fire even at its very core and that is what haunts you most—that is what you cannot bring yourself to face and so you invent me, The Dragon, your own fears made manifest—but please know this: the wind that blows through the orange blossoms and whips this child’s gown and hair also cools my nostrils and scales and bones and it blows behind me into the cave, where I have laid and hidden a thousand and more eggs, and that same wind blows, like belly breath from my own body, outward over the chained child and beyond her into the entire known world, including you, who come armored in far less metal than I have hoarded in my caves yet still you charge.Dear sir, I beseech you, as I unfurl my wings and take a great breath, lower your weapon and embrace me for I am you and even if you kill me today I will be resurrected, a phoenix rising in flames, hissing from within the darkest recess of your heart.

Cleolinda, 14,

Pagan, Virgin, & Princess

T

hough I have always dreamed of Leptis Magna and its statuary and mosaics and circus and amphitheater and of floating naked in the Mediterranean and bending the world to my will, I never imagined my father would sacrifice me to certain death—I did know that he would sell me to the highest bidder, to whoever had the greatest army or the largest estate or the most power, use me as a mere string to tie a knot between two kingdoms—I always knew this, the same as I know that every lady-in-waiting who has attended me, combed my hair or fluffed my pillows or polished my shoes, wished in her secret heart to be me, the doted-upon princess—to be the lone child of King Ptolemy and Queen Sa’diyya—to be the one heaped with diamonds and attention, dressed in the finest Egyptian cottons and dyed linens, and studied by every woman who has enough ambition to be jealous—though each of these maids stands worshipped by every mother of six toiling in the street with rags on her bones, who ventures off to the market, the abattoir, the spring-fed well, and returns home to her brood of indifferent sucklings, her arms laden with a sack of grain, a shank of lamb, a drawn skein of water, to cook for a husband who does not hate her, only that and nothing more—these women, in turn, are both despised and admired by prostitutes with rut-bruised knees, blistered backs, and unforgiving aches in the middle of their bodies—yet these harlots of the street who envy these domestic women’s safe lives, would never worship me, because I am, after all, one of their own.This noble fool comes scampering up—body heaving and heavy beneath all that metal—if he kills the dragon and frees me from my chains, I know I will marry him and convert to his god but only if he grants me one favor more:

Good sir of the Royal Order of Christ, slip into my father’s chambers and find him sleeping and slit his awful pimp throat

.

Judicium Dei

or Trial by Combat: Le Gris v. CarrougesIn the Last Trial by Combat Ever Decreed by the Parlement of Paris, Saint-Martin-des-Champs, on Île de la Cité, Paris, France,

December 29, 1386

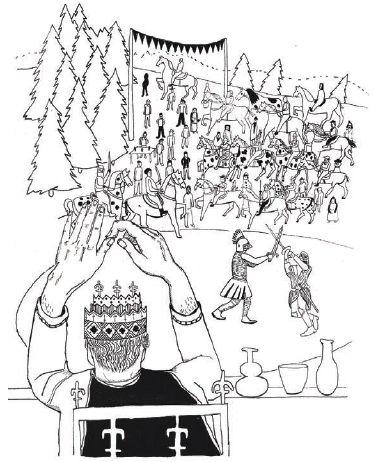

Charles VI, 18,

Mad King of France

I

cherish a good spectacle, the Lord knows I do, tournaments and banners and armor and arms, and I have entered them myself, the thundering steed between my thighs, the lance leveled heavy and true, but last night my only son, three months old and sickly, succumbed and died—Queen Isabeau is distraught, the fairness gone from her cheeks, the luster from her hair, and Sir Jean’s lady-wife, Marguerite, has also given birth but does it belong to her husband or Jacques, the squire she’s accused of rape—how can any man know the truth of such an accusation and so I am proven mortal—the joy of the joust is not with us today but rather certain death as in the constant wars with England or my own father or my own son—today one of my bravest men will die—his body will be stripped to the skin, dragged naked to the gibbet, and hung in Montfaucon, where vultures and magpies will feast on his limbs and eyes—if Marguerite’s champion, her husband, should fail, then she too shall forfeit her life for swearing a false oath against my Court—God’s will be done, she will burn at the stake and hang in public alongside Jean, the rot of their flesh on the wind blowing throughout the city—a spectacle, true enough, but I do not cherish its kind—she is dressed in black upon a black-draped scaffold as if already in mourning and so too am I—on the morrow I bury the prince and the land is hard and cold though the earthworm never sleeps—it crawls through the earth as surely as my mind, with the stealth and force of ten British armies, and I would destroy him with a mace if it would not also mean self-slaughter—a tear tickles

my eye and I know it is but the earthworm itself creeping from its lair, its head probing forth, and I stand and shout,

Anon, Anon, Anon

—my voice echoes off the high wooden walls, the throng of viewers, the silent guards, and the priests who have cleared the field of their makeshift altars and host—what do we need with God’s verdict today?—am I not His earthly delegate made manifest in law? If so, then why could I not conjure the truth, why my blasted hesitancy, my dead child? Damn the earthworm! Lest he be God’s chosen emissary and the blood of a knight may bring about the resurrection and rapture!In the center of the field, the grand marshal holds aloft a white silk glove until all grow quiet and I am leaning forward out of my box when he shouts,

Laissez le aller!

and tosses the glove high in the air and I want to leap for it, catch it, and wipe my face clean, but instead I merely clap and clap like a child at play.

Jacques Le Gris, 50,

Newly Anointed Knight (Gray Coat of Arms)

W

e have broken our lances and with my axe I’ve beheaded his horse and Jean fell to the ground and disemboweled mine and so we were on foot until I lashed open his leg, the blood luscious over his thigh—the sun is noon-high and I sweat and stand over the man, whose breath comes like passing clouds—I recall the day I came to her and she raised a hue and cried,

Haro! Aidez-moi! Haro!

till her voice turned raw and blue and I had my desire of her, her hands tied behind her back and she kicked like a good mule and when I took my leave I donned my wool cap, still warm from having been stuffed in her moist mouth—I raise my long sword over my head and watch its tip touch the pale sun and I see a hawk on the wind and archers in the stands and, as I bring the steel down, the marshals by the gates in the wooden walls and poor Jean lying in the dirt like a thing tossed aside—poor foolish Jean bade me be his first son’s godfather not knowing I too was his own true father and his first wife took me as her own deep secret until the day she died—which is worse, Jean having no heir to inherit his land or me having a failed father with nothing to hand down? At an early age I swore that by God’s cloak I’d make my mark and so I’ve taken upon my grievance to amass a fortune, to take all the things of this world I’ve wanted, and now I will have Jean’s estate and child as well.I miss and the steel buries in the sand and somehow I land facedown and his breath is in my ear, the sound as wet and rogue as the heave of sex, and he has me pinned like a woman and I am helpless and he turns me over and pushes his four-inch

dagger slowly into my underchin and I feel the blood choke there and throb out of me like

petite mort

and the sun is there and the ramparts are there and the knights and the priests are there and the executioner and Marguerite and Count Pierre and my lawyer and ten thousand witnesses have all gleaned my guilt but God knows from the voice of our confessions that I am innocent of any crime that Jean would not have committed himself.

Jean de Carrouges, 51,

Knight (Red Coat of Arms)

I

n this age-old grunt of combat, my hearing has gone dull and mute as if I’m underwater, yet still I hear sweet Marguerite saying again,

He came to me whilst thou were away in Scotland defending France’s honor

, and my mother,

He sent me on a needless errand to Alençon

, and my father gone now these many years,

Your life is but a balance of just and unjust and you are the hinge it matters upon

, and Count Pierre in the trial I brought against Le Gris,

The innocence is with my squire

, and the king himself, my liege lord,

I cannot choose, I will not choose, I shall not choose

, a whole cacophony of voices drowning the gasp of the spectators when they saw my flesh open and I stumbled to the ground and began like a crab to scuttle away—oh Lord, I beseech Thee, do not render me a cuckold, Thou hast afforded me valor and victory in forty-one battles but if I lose today, all is lost, my honor will fly and be hanged with my body—the talk in the Court and courtyards and market stalls will not be of my steel and of my strength but only of the gray in my beard and my faithless M, whose father, ’tis true, was a traitor to the Crown, but she is pure, isn’t she, Lord—my living son will no longer be my son, but his, and my land no longer my land, but his—oh Lord, I’ve sworn three oaths to Thee today, called upon Our Lady and Saint George and praised the Passion all in Thy holy name, amen—Le Gris’s legs go awobble and he blunders facedown and I’m on him and I bang open his visor with the pommel of my dagger and I demand he unburden himself of sin—even as I push the blade into his soft flesh he says, blood frothing in his

beard,

In God’s name and on the damnation of my soul, I have no crime to confess

, and I push the steel in farther and say,

Confess, man

, and he does not and so he dies and I win and I am alone, questioning the nature of Truth.