The Book of Duels (11 page)

Authors: Michael Garriga

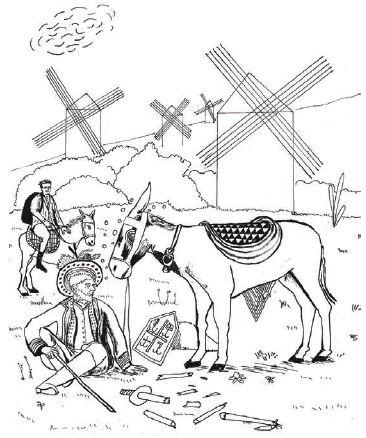

Tilting at Windmills: Nicholas v. Quixote

On the Plains of La Mancha, Campo de Montiel, Spain,

March 15, 1565

Since we cannot change reality, let us change the eyes which see reality.

Maximus the Confessor

Argus Nicholas the Giant, Ageless,

in the Guise of a Windmill, from Pallene but Now of Spain

T

he old man is not as daft as he may appear to be—we are, indeed, the giants that he sees—after Heracles and his army of fiends destroyed most of our warriors, my surviving brethren and I pledged ourselves to love, to peace, to song, and so became courtiers, immense and strong and loud—alas, we came to this terrain, wide and wondrous Spain, and soon our melodies attracted Malady, goddess of the plains, and of the winds and of the rains, who appeared to us as if from some radiant dream, bejeweled in myriad grains and draped in olive branches and antlers, and our poems bent her ear and wooed her heart and she was our dear muse, our master, our art, and we thrived until her jealous husband, Freston the Mad Magician, cast a spell that stole our voice and turned our skin to stone—no more the spinning of yarns, now only our sails nigh two leagues long twirling over and over and over again—we stiffened solid as trees receiving the breeze blown across Sierra Nevada and birds light and shit on our shingles and the sun burns the lye white off our skin—yet this old man sees clear the giant I am, the old warrior I was, and he challenges my statue self—he shouts for me to glance the way to Heaven’s gate before he charges and now it’s too late to turn back and so, in turn, I spin him ass over end or trim horse over limb and shatter his lance and drop him on his pants and, as surely as one look from monstrous Medusa could turn flesh to stone, he has made me quick again.Would that I had hands and the chance, when the next winds swung my arms low, I’d dust this knight’s bottom and lift him high thereafter for he has, sweet prince, reminded me who I truly am.

Don Quixote, 49,

Knight Errant de la Mancha

I

am not fool enough to believe this windmill a giant, but what right man would not choose to live in a world filled with maidens, beautiful and fair, high romance, a dragon’s lair, and a chance to earn a king’s ransom, compared with the daily life we live? So I set out with a dry old nag and this fool by my side to roam the country over, courting adventure in order to quell the searing fear of death that is in every man, and poor Panza, he cannot see because he has no eyes for fantasy, for dreams beyond his monstrous belly, yet I know these things exist, the same as I know that God does not, yet there I am weekly at mass, thumbing my rosary, a devout, praying at each station of the cross, all because I desire the approval of my own father, who once my mother had passed locked himself away in the library and read himself to death, and so too have I consumed my mind full of fantasy though I will not be my father, pining loveless and a loon—I know that before me, squat and bright in lye-washed white paint, is no giant at all, but I will it to be, and so it is—how can a man who knows he is mad be truly mad after all, especially one who knows his life draws near to close and wants nothing more than a moment’s pure good grace—so,

Hie, vale anon!

I spur dear Rocinante on and into the giant’s flailing arms, aware that his time too is at hand and shall like my father pass from this world.I smash my wooden lance against his jaw but, like the Reaper, he grabs my steed and self and sends us over—the world

whirls by like a Bedouin dervish and slams us to the ground and in the distance I see clouds in the shape of buzzards, beautiful and languid and hungry, and just above me, the windmill’s slow, eternal spinning hands.

Sancho Panza, 47,

Illiterate Squire

U

nder this unforgiving sun, I sit muleback in the meager shade afforded by a lone olive tree and I pick the fruit and bite and find it bitter. My bile rises for the want of brine. And of capers and of caper berries and of all things pickled and salty. My donkey has white rings around his eyes like a bull’s-eye and me without a dart! His head is like a giant shovel, his large jutting jaw like an insatiable maw! Oh what I could eat if I had that hasp: a dozen

bocadillo con jamon y queso de cabra

because I’ve always loved the bastards. And here’s the old man taken leave of his senses while on a service he declared that God has blessed but it’s plain to see there will be no

boquerones en vinagre

; no

ajo blanco

with a nubile Mudejar to grind the garlic with mortar and pestle and no bread to sop into it; no bladders of wine at the ready; no Gypsy girl to tickle my feet with rosemary branches, as we moon over my island paradise, where I serve as lord and governor and bring together the Moor and the Jew and the Catholic alike: come friends, one and all, bare your chests and souls and be my guests. My ass is swayed and my belly is bulging with the fat of years and indolence and friendships raised and toasted and gulped. Don Quixote has promised me this sacred

isla de paz

, but now, seeing his broken body lying in the earth, all hope for it is dashed. Shall I leave him, return home to my wife, who waved me a fond farewell, or to my daughter, who is old enough to marry, herself?True, the old man is little more than bluff and bluster, hot wind and noisy clang, like the time in my hometown when the wind rose and loosed the Santa Maria bell from its

moorings and blew it out the church tower, bats bursting forth in all directions, the bell and frayed rope fell an impossibly long time and crashed in the earth, cracked, and let off one last toll that sounded in the square for nearly one whole year, the noise caught somehow in the winding streets of the old barrio, confused and lost, with no way nor want to find its way home.

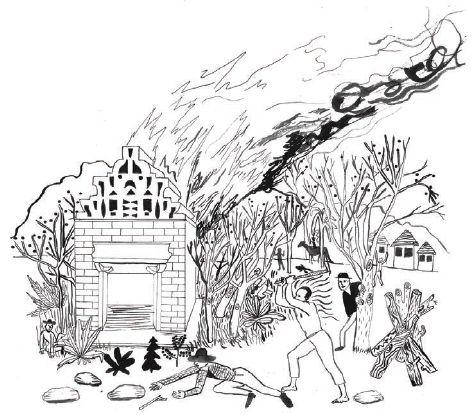

On Moses’s Failed Insurrection: Unbada v. Cantrell

During a Slave Uprising outside Baton Rouge, Louisiana,

March 5, 1811

Unbada, 28,

San Domingan Slave on the Picou Plantation

I

am awake but cannot flesh out the haints of sleep, as though my life’s become a dream, a shade passing before closed eyes. I cannot conjure my name nor who I was, and if I can’t, then was I ever? And if not, then what am I now? I reach for fleeting images—a woman’s parting lips, a child’s hair soft against my palm—when an odor comes over me, strong as pan-tote bacon fat frying in a deep pot, but like something else too I can’t quite call, and there’s a roar in my ears like waves crashing ashore and that smell drives my feet forward; it is salty as seawater and like everything I’ve ever wanted—a hug from my mother, a free moment to drum and enjoy the one-pot feast—I’m chest-punched, the air exploding from my body, and the sky tilts before me and I land on my back and I yearn to lie still and rest here forever but again I sniff that weird scent on the wind and am up once more, steady shuffling like the insatiable drive of mules, and all of my labors and all of my loves pass from me—I can’t resist this wanting to know the source of such intense perfume—my feet propel me and I am trying to say my name, though it comes out only a moan, and that water keeps roaring in my ears and I am bellowing like a belly-sick sow, wanting an answer to the question of that smell, and then I see Boss John and that odor becomes scythe-sharp and I smack my tongue against what’s left of my last meal, whatever it was, grainy remains like mullet roe in grits, and all I can see in the world is him and his smoking gun, but before he can fire again, I realize that he is the answer and I must have him.