The Book of Duels (13 page)

Authors: Michael Garriga

Slap Leather: Hickok v. Tutt Jr.

In the Quick-Draw Duel That Gave Birth to the Wild West, Springfield, Missouri,

July 21, 1865

James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok, 28,

Abolitionist, Union Scout, & Gambler

W

as a time I rode with Colonel Lane and we took shot from border ruffians; or ’at knife fight with Conquering Bear, who I gave the old sockdolager to, till his blood soaked my buckskin britches; or how I bluffed Kit Carson with a two and a seven, my last ducat laid out on the table afore me; or the shootout I had with ’at cockchafer McCanles at Rock Creek when he bullied me as I mended the stamina I allers had; or when I ran the skirmish line at Wilme Creek and a dozen Johnny Rebs shot my way at’wonce, somehow, God only knows, missing me each and ever time—now here’s square-fisted Tutt, the sodbuster in a linen duster, dead set on giving me Jesse—he stands afront of me, thumbing my eye by wearing the Waltham watch my weeping ma give me when I left home ten year ago—I broke her heart on account I thought I’d killed that cunny-fisted Colston boy—I swear, ain’t a single damn thing scared me since that black bear in Raton Pass swiped me off my horse and took my six shots in her belly like runaway orphans and tore my shoulder clean out its socket and I even took my Missouri toothpick and stobbed her neck and I stobbed her thigh but she clean tore my head wide open, took my scalp half off like a swinging saloon door, and my fears musta fell out in the rock-strewn dirt, I swear, ’cause right then and right there I was reborn, fearless, and I buried that blade in her heart and killed her graveyard dead, I did.My trigger finger taps the pistol butt as calm as turning a trump—there are so many ways to die, I reckon a man oughta

consider hisself lucky, notorious at the least, to celebrate these victories over Death—specially, when it gets told and retold, if he’d shot twenty-four border ruffians with only six bullets, killed the strongest gotdang Indian chief with but his bare hands, or had the hair on his ears singed off when ever durn two-bit Reb shot his way at’wonce—they all wanted me affrighted but really what is there to fear? Nothing, ’cept being forgotten and I don’t reckon that’s gonna happen to me neither: so buck up, Tutt—you ain’t got to grieve too deep ’cause after I kill you here and now, you’ll be infamous too, and I’ll be hanged if you won’t have been the fastest gun in all the West, until you met me.

Davis Tutt Jr. 29,

Confederate Veteran, Perpetual Sidekick, & Gambler

I

come out the livery stable to find him cool as Ozark dew and leanin caddywamp on a pillar of The Lyon House and I stand tall as can do and open my coat to show his watch hangin from my fob chain for all who care to see—his bright blue eyes turn that steel gray they get when his blood is up—he is a Yankee, Bill is, and I kilt a dozen or more of his kind in the war but all of em taken together ain’t his equal—he and I rode the ranges this spring and drank the taps dry and I brung him out to my kinfolk farm where he sweet-talked Sissy and sneaked off with her to canter rear of the barn and he went off and did her dirt—before then I’d have torn the eyeteeth out a wolf’s mouth just to get corned with him again—I swear I wisht I ain’t knowed what all he done, so I ain’t have to make this choice here—family or friend, honor or fear—’cause I’ve seen him shoot and he is true with a bullet and he got the good nerve cept when it comes to cards—that tick in his jaw means he ain’t got the trick nor the bluff he shows and so I aimed to beat him out his bankroll but snatched his watch instead, just to break his heart a bit, and now he wants this spectacle show so he hollers across the square and I, I tug my piece from the holster slung low across my hip and I am in the dad-blamed war again—brother versus brother—I see my shot bury in the dirt, spittin up a tornado gainst his moccasins, his thick thighs in leather leggins, his narrow waist, his broad buckskin-covered chest, and on up to where the white smoke hides his hand and hair and fine, fine face:I am blown clean through and goddamn it hurts—the whole blasted town of looky-loos stares from behind the water troughs and billiard hall windows and saloon doors—

Send for the surgeon, you sonsabitches, don’t just stand there stock-still and watch me die

—my scalp prickles and I fall on my haunches, sittin in some mud—who knew I had all this life inside me just waitin to come on out?—my head swoons silly and I close my eyes and feel Bill’s hand steady my shoulder and I realize I have often wanted his hand on me and I look up but he is not there and I fall sideways and I just keep falling and falling and

Dr. Aleister Greggs, 63,

Former Surgeon, Present Drug Addict, & Future Dime Novel Author

I

exhale the smoke and a certain peaceful silence blows over me and I roll to my other side to look through the dingy lace curtains of Lu Yang’s upstairs window expecting the clouds that attend high noon, but instead the evening sun shimmers like a crimson pool on the tin roof of The Lyon, with its venetian blinds and fancy chipped-ice drinks, and beneath stands Hickok, the biggest toad in this whole mud puddle, his fingers all a-wiggle above the hog leg jammed in his red silk sash—this morning he and young Mr. Davis called on me as if I were the swamper sent to sweep the sawdust and slop the spittoons but I storied them on the preacher who I saw shoot a newspaper man back in ’59, who bled to death jabbering on my parlor room rug—shot him in a duel right in front of the dead man’s boy who later, I heard, gave that clergyman the short end of the horn—I gave both boys to understand that I’d not be put upon to clean any more wounds, nor ease the pain in any way of men who shoot one another, and I assumed that had settled the score and so we’d have no bloodshed today—across the square, where flies have gathered on every pile plopped in the dirt, comes ornery Davis walking down Business Street, where wagons and horses and mules stand before the mercantile and blacksmith shops, and he’s all squinty-eyed against the sun, his long coat blowing in the wind, and I conjure in this yellow silence a hawk’s shadow inking the earth between the two men and then the bird screes—I can’t get shed of all the death cries of Quantrill’s crazed bandits back in the

war—boys, just boys, slathered in their own gore and I’d ply them with opium powders till I took a mind to dope myself and when the war finally stopped I prayed for a certain peace, but those ghosts speak shadows that never cease nor do they ever sleep nor disappear.Their pistols jump together as in a dance and the smoke rises and Davis spills a mess of blood and collapses into the mud of his own making and hollers for me to help and Hickok turns back inside the saloon for a belt of rye, I presume, and I ease down the water-stained shade on the world and roll back over and take the pipe to my mouth for one more puff of God’s own medicine, and as though it were the lost souls of every murdered man I’ve ever met, I hold that smoke in my blood and brain and lungs until it burns and has to come out.

The Black Knight of the South (A Gothic Romance): Moran v. McCarthy Jr.

In the Fourth and Final Duel of the Day on Bloody Island in the Middle of the Mississippi River, Near St. Louis, Missouri,

March 23, 1874

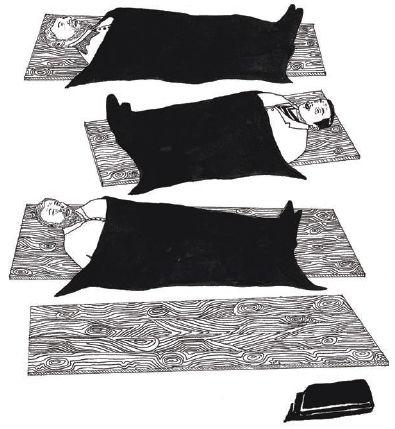

Cadet Moran, 14,

Youngest of the Moran Clan

M

y brain’s a dang swarm of bees and that judge just keeps on a-counting and so I count too: my three dead brothers laid out on cooling boards, the color yet in their cheeks; my first duel ever and his fourth today; one bullet in this one pistol in this one life; and six vultures lazy-eighting on the wind, which is God’s breath come to cool my skin now as I lick my wrist, thin and clammy. My tongue is pruned. My mouth, cotton. My legs are logs on fire. And the river and the smell it carries from a thousand miles north, is pulled past here roaring like a dad-durn tornado and my numbers go all jumbled and I want to dive in the water and be done with this mess but if I ever wish to look my kin dead in the eye again I must be here to defend Sister’s honor and avenge my brothers’ deaths—though I’ve never worked a hard day in my life, instead of these paces I’d rather be walking behind a mule like the tenant farmers who plow our land, or better, digging in the dirt for worms to go cane-pole fishing in Simmons Stream or swimming out there with Jeanette or chasing her through those fresh-turned fields, pulling her ponytail instead of the trigger to this gun that weighs nigh as much as me, but I am here, fingering this cold iron curve, as the judge calls twenty and I stop and spin slow as the seasons change and I see my man and I can’t shake the blasts fired earlier today nor the way my brothers bellowed when their blood burst from their bodies, freckling the sand—I clamp my eyes tight as pickling jar lids and the judge hollers,

1, 2, 3, Vale—I hear the report clear as church bells but I swear I ain’t even squeeze the trigger. I swear. Yet there he is somehow splayed on top of Sister and she’s a-kissing his face and I fall to my knees hard in the sand and pray that my brothers now may all rest in peace, though I know I never will again.