The Book of the Poppy (10 page)

Read The Book of the Poppy Online

Authors: Chris McNab

John Alexander Raws was British-born and his family emigrated to Australia when he was a child. In 1915 he joined the Australian Corps, and was sent to fight on the Western Front as a junior officer. He was killed in August 1916 in the Battle of the Somme, but left behind him a striking sequence of letters to the various members of his family. The early letters are full of examples of nervous manliness, such as this one to his father, written on 12 July 1915:

I received your letter this evening, just a few minutes after I had passed the medical test for enlistment. I propose to go into camp in a week or two – probably Wednesday week, or Monday week – today fortnight. Meantime I shall study and drill.

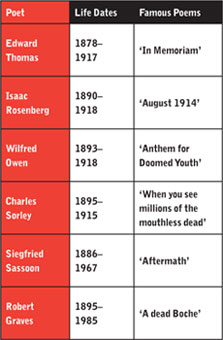

FAMOUS BRITISH FIRST WORLD WAR POETS

If I had received your letter before, father dear, it would have made no difference. My decision has not been sudden. My mind has been practically made up for a month or so – before the recruiting boom to which you refer – but I was waiting to advise you immediately everything was fixed, and I was accepted. The reduction of the standard has enabled me to get through. [Raws had been rejected for service the previous year, having failed a health evaluation.]

I hope that you will be proud to think that you have two sons – who were never fighting men, who abhor the sight of blood and cruelty and suffering of any kind, but who yet are game to go out bravely to a war forced upon them. There are many men, wealthy and strong, who should have gone before me, and have not. But can that excuse me? Not for one moment.

I do not go because I am afraid that my friends may think me a coward if I stay, but I do feel in going that in my small way I am conferring upon you and dear mother what should not be a crown of sorrow. You would not have your son, whatever else, a craven – one who would say that he thought others should go, but would himself hang back. If I prove unfit for service, well and good. But it has to be proved.

I said before that I claimed no great patriotism. No government, other than the most utterly democratic, is worth fighting for. But there are principles, and there are women, and there are standards of decency, that are worth shedding one’s blood for, surely.

The sentiments in this letter reflect those of many men eager to join the war effort. Very few actually rejoiced in thoughts of violence and combat, but were still compelled to ‘do their bit’ for their country and community, while also avoiding the very real threat of being branded a coward. However, there is a deep shift in tone as Raws became more familiar with the realities of life on the frontline. This letter was written to a friend on 20 July 1916:

I am no more in love with war and soldiering, however, than I was when I left Melbourne, and if any of you lucky fellows – forgive me, but you are lucky – find yourselves longing to change your humdrum existence for the heroics of battle, you will find plenty of us willing to swop jobs. How we do think of home and laugh at the pettiness of our little daily annoyances! We could not sleep, we remember, because of the creaking of the pantry door, or the noise of the tramcars, or the kids playing around and making a row. Well, we can’t sleep now because six shells are bursting around here every minute, and you can’t get much sleep between them; Guns are belching out shells, with a most thunderous clap each time; The ground is shaking with each little explosion; I am wet, and the ground on which I rest is wet; My feet are cold: in fact, I’m all cold, with my two skimp blankets; I am covered with cold, clotted sweat, and sometimes my person is foul; I am hungry; I am annoyed because of the absurdity of war; I see no chance of anything better for tomorrow, or the day after, or the year after.

The letter here conveys a man stretched to his physical and mental breaking point. Subsequent letters frequently dwell on the theme of madness, in himself and in others, and his hatred of war builds to a fever pitch just days before he was killed, as in this letter to his brother on 12 August:

The glories of the Great Push are great, but the horrors are greater. With all I’d heard by word of mouth, with all I had imagined in my mind, I yet never conceived that war could be so dreadful. The carnage in our little sector was as bad, or worse, than that of Verdun, and yet I never saw a body buried in ten days. And when I came on the scene the whole place, trenches and all, was spread with dead. We had neither time nor space for burials, and the wounded could not be got away. They stayed with us and died, pitifully, with us, and then they rotted. The stench of the battlefield spread for miles around. And the sight of the limbs, the mangled bodies, and stray heads.

FUTILITY

Move him into the sun –

Gently its touch awoke him once,

At home, whispering of fields unsown.

Always it woke him, even in France,

Until this morning and this snow.

If anything might rouse him now

The kind old sun will know.

Think how it wakes the seeds –

Woke, once, the clays of a cold star.

Are limbs so dear-achieved, are sides

Full-nerved, – still warm, – too hard to stir?

Was it for this the clay grew tall?

– O what made fatuous sunbeams toil

To break earth’s sleep at all?

Wilfred Owen, 1918

We lived with all this for eleven days, ate and drank and fought amid it; but no, we did not sleep. Sometimes, we just fell down and became unconscious. You could not call it sleep.

The men who say they believe in war should be hung. And the men who won’t come out and help us, now we’re in it, are not fit for words. Had we more reinforcements up there many brave men now dead, men who stuck it and stuck it and stuck it till they died, would be alive today. Do you know that I saw with my own eyes a score of men go raving mad! I met three in ‘No Man’s Land’ one night. Of course, we had a bad patch. But it is sad to think that one has to go back to it, and back to it, and back to it, until one is hit.

The final words in this letter are horribly prophetic, for Raws was killed just days later – he was hit by a shell on 23 August, and died instantly. The power of Raws’ letters transcends the distance of time. He was just one of the millions of war dead from that conflict, but his letters present a real man in real time, responding to a human crisis enveloping him.

Since 1918, the literature and letters of war have continued to be written, new conflicts providing fresh contexts for reflection and remembrance. To read such literature does not require by any means an interest in military history, nor a desire to learn about the ways of war. Instead, it provides both a window into how humans think and behave under the most extreme circumstances, and poses the implicit question – what would you have done?

QUOTES FROM THE LETTERS OF JOHN RAWS

12 July 1915

– ‘… there are principles, and there are women, and there are standards of decency, that are worth shedding one’s blood for, surely.’

27 May 1916

– ‘We whistled and sang the Marseillaise as we tramped … And my word it was heavy walking! This is marching order.’

9 July 1916

– ‘Against the front breastwork we have a step, about two feet high, upon which men stand to shoot. When there is a bombardment nearly everyone gets under this step, close in against the side.’

20 July 1916

– ‘The shells are coming from all directions by the thousand, ours and theirs, but I’m resting in quite a comfy little machine gun emplacement. We hope to be out of it in a few days, thank goodness. Our losses have been heavy.’

8 August 1916

– ‘I was buried twice and thrown down several times – buried with dead and dying. The ground was covered with bodies in all stages of decay and mutilation …’

12 August 1916

– ‘I lost, in three days, my brother and my two best friends, and in all six out of seven of all my officer friends (perhaps a score in number) who went into the scrap – all killed.’

19 August 1916

– ‘Before going in to this next affair, at the same dreadful spot, I want to tell you, so that it may be on record, that I honestly believe Goldy and many other officers were murdered on the night you know of, through the incompetence, callousness, and personal vanity of those high in authority.’

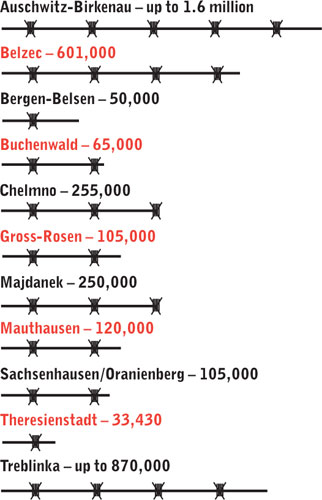

DEATH TOLLS OF MAJOR NAZI EXTERMINATION/CONCENTRATION CAMPS

ONE OF THE IRONIES

of war is that a situation that sees the worst in human behaviour at the same time can bring out the best in people. We witness this with great clarity during the annual Poppy Appeal. Not only does this event represent a national and international act of remembrance, it also demonstrates a very practical desire to help veterans, military families and all those affected by the consequences of war. For example, some 350,000 volunteers and staff of The Royal British Legion work every year to make the Appeal possible, many of them giving up large portions of their spare time. Through their efforts, more than £40 million is raised annually, which then goes to good causes ranging from supporting bereaved families through to rehabilitating injured veterans. Numerous other organisations work throughout the UK to deliver support for soldiers (former and current) and their families, some providing specialist medical care found almost nowhere else. If anything, the presence of these organisations reminds us that the instinct to care is just as strong in humanity as the instinct to fight and destroy.

LIFE ON THE OUTSIDE

Military personnel tend to have fairly tough and resourceful personalities. They are used to high-pressure demands of a type rarely faced by those in civilian life. Mistakes in a war zone can literally result in lives lost. Combat troops also have to negotiate the prospect and actuality of killing people, an act that frequently leaves an impression on even the most hardened character.

Yet for all the mental resilience possessed by military personnel, life for them back in the civilian world can be hard, whether the return is the result of injury, the end of a term of service or being made unemployed. Life inside the forces tends to have a high degree of purpose and team loyalty, whereas in the civilian environment the bonds between people, especially in the workplace, are typically far weaker and more self-interested. A veteran can thus emerge from a world in which he manned a multimillion-pound armoured vehicle, or fought close-quarters actions with insurgent forces, into one that cares little for his past, indeed may even feel somewhat threatened by it. By consequence, the soldier can struggle to fit back into regular life, with potentially severe consequences for the soldier and his or her family.

In one sense, Britain and many other nations have often struggled to make society welcoming for its veterans. Following the world wars, huge numbers of disbanded troops returned home in a rapid timeframe, resulting in intense competition to find work. In Britain, both of those conflicts also left the UK in economic desperation, making the jobs market even tougher for many of the soldiers. After the First World War in particular, Britain’s citizens were treated to the unedifying spectacle of limbless veterans reduced to begging on the streets, their medals for bravery worn across the front of tattered coats.

Another adjustment the returning soldiers had to make was social. During their time away, women had stepped up in their millions to work in war industries, finding financial and psychological independence while their husbands and boyfriends were away. Not surprisingly, many women were reluctant to go back to traditional female roles after the war, and were often rather alienated from the men who returned, very different from the men who had left. Thus the UK divorce rate in 1948 was more than double what it had been in 1938. Similarly in the United States, the divorce rate was 20 per cent in 1940, but 43 per cent in 1946.

Another problem for veterans back in the civilian world was coping with what they had been through. By the end of the First World War, British medical services had treated 80,000 cases of ‘shell shock’, resulting in what we now call combat stress and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). These were only the most visible cases – tens of thousands of other cases were likely to have gone undiagnosed and untreated. The symptoms of this condition vary, from periodic nightmares and anxiety through to complete physical breakdown and suicidal and violent acts (such as domestic violence). The triggers are also equally varied. For some soldiers, a single horrifying incident can embed itself in the memory and only emerge, like some forgotten ghost, in later life. For other soldiers, the repeated daily grind of combat and its associated stress produce a complete and prolonged mental burnout. The psychology of PTSD was little understood after both world wars, meaning that millions of men went through the rest of their lives in torment and confusion, little understood by the society into which they were trying to reintegrate. All sides were affected by the phenomenon. Amongst German troops, for example, there were reports of up to 33 per cent of all military hospitalisations being psychological by 1944–45.