The Book of the Poppy (4 page)

Read The Book of the Poppy Online

Authors: Chris McNab

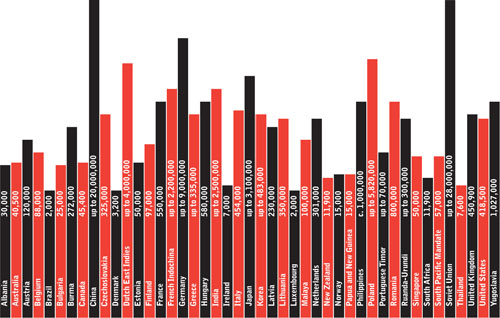

SECOND WORLD WAR CASUALTIES (DEAD, WOUNDED AND MISSING)

FRONTLINE VOICES:

THE BLITZ

The following is an extract from the

Manchester Guardian

, recording just one of many incidents during the Blitz:

Children sleeping in perambulators and mothers with babies in their arms were killed when a bomb exploded on a crowded shelter in an East London district during Saturday night’s raids. By what is described as ‘a million-to-one chance’ the bomb fell directly on to a ventilator shaft measuring only about three feet by one foot. It was the only vulnerable place in a powerfully protected underground shelter accommodating over 1,000 people. The rest of the roof is well protected by three feet of brickwork, earth, and other defences, but over the ventilator shaft there were only corrugated iron sheets. The bomb fell just as scores of families were settling down in the shelter to sleep there for the night. Three or four roof-support pillars were torn down and about fourteen people were killed and some forty injured. In one family three children were killed, but their parents escaped. Although explosions could be heard in all directions and the scene was illuminated by the glow of the East End fires, civil defence workers laboured fearlessly among the wreckage seeking the wounded, carrying them to safer places, and attending to their wounds before the ambulances arrived.

Manchester Guardian

,

9 September 1940

BRITISH BOMBER CREWS

Although British bomber crews delivered some of the most devastating raids of the war against German cities, they in turn faced the worst odds of survival of almost any branch of service. The threats they encountered included swarms of German fighters and night-fighters, dense anti-aircraft fire, enemy radar (which alerted enemy gun and fighter crews long before the bombers arrived on target), adverse weather and mechanical failure. Some 125,000 men served in Bomber Command, and 55,573 were killed, a mortality rate of 44 per cent. Bomber crewman life expectancy dropped to around six weeks in 1943–44, much less than that of an infantry officer in the trenches of the First World War.

Returning to the military campaign, Britain’s armed services casualties during the conflict were significantly fewer than the First World War, although the figure of 383,000 is still chilling. During the six years of war, the armed services grew in size (via conscription), professionalism, technological might and influence. They fought in every conceivable theatre, environment and condition – the jungles of Burma, the deserts of North Africa, the icy landscapes of Norway, the mountains of Italy, the hedgerows of Normandy, the bitter Arctic and Atlantic waters and the skies above Western Europe. Armour, artillery and air power became the war-winning instruments, while on the oceans the supremacy of the battleship was replaced by the aircraft carrier, a weapon system chiefly developed by the United States and Japan. There were also new types of soldier – each side developed units (such as the British Special Air Service) of what we would now refer to as ‘special forces’, men tasked with the most dangerous and secretive of assignments, generally well behind enemy lines.

Given the way the Second World War engulfed the planet in destruction, it seems almost churlish to speak of winners and losers. Yet the fact remains that not only did Britain, through the efforts of its armed forces, avoid the fate of occupation that visited much of the rest of Europe, it also played a critical role in liberating territories from Nazi and imperial Japanese control. At the same time, we must recognise that these ultimate goals would have been impossible without the vast military and industrial resources of the United States and the Soviet Union. By 1945 Britain was somewhat in the shadow of these emergent superpowers, but we nevertheless owe a debt of gratitude to the generation of those years, who in many ways literally made possible the freedoms we take for granted today.

MODERN WORLD, MODERN WARS

The post-Second World War era has been a turbulent time for the Britain’s armed forces. From 1945 to the present day there have been two competing demands. The first is economic pressure. The armed forces have been through numerous periods of cutbacks in both manpower and spending on resources and technology. Yet running against the grain of the cutbacks has been the fact that Britain’s armed forces have rarely seen a year when they were not in action. Some of these conflicts have been major, such as the Korean War (1950–53), the Falklands War (1982), the First Gulf War (1990–91), the Iraq War (2003-2011) and the war in Afghanistan (2001–present), the latter being the longest-running continuous conflict in British history. At the same time, British soldiers have served in numerous insurgency and peacekeeping conflicts, low-level but destructive wars that can see a soldier’s role fluctuate between ‘hearts-and-minds’ humanitarian work and outright combat with dizzying regularity. Such actions include the Malayan Emergency (1948-60), the campaign in Aden (1964-68), long and testing service in Northern Ireland (1969–98) and operations in the war-torn Balkans in the 1990s.

The nature of warfare since 1945 could not have seen more dramatic transformations. Almost every aspect of combat technology has been revolutionised by computerisation, so that today we are no longer amazed by pilotless unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), precision-guided munitions (PGMs) that can hit pin-point targets after miles of flight, and military surveillance satellites that can map the battlefield in real time from hundreds of kilometres above the surface of the earth. The emphasis on technological solutions to military problems, plus a deeper political aversion to casualties amongst many nations, has thankfully resulted in a definite limitation of battlefield death tolls. For example, most British infantry divisions fighting in Normandy in 1944 would have taken more casualties in a week than the entire British losses in the Afghanistan conflict.

Yet such comparisons rather miss the point. Britain’s soldiers, sailors and airmen have continued, and will continue, to make the ultimate sacrifice in war at home and aboard. For the dead and wounded, and their families, the impact is the same whether the casualties of an engagement number in the thousands or just a single individual is lost.

TO TRACE THE

history of the Remembrance Poppy, we have to journey back to a time and place stripped of almost all beauty and compassion. Belgian Flanders represented the northernmost point of the Western Front during the First World War, once the trenchlines had been inscribed in the earth by the end of 1914. Between 1914 and 1918, Flanders became one of the most devastated regions of the entire battlefield. The British held a salient – in effect a bulge in the frontline – that kept the city of Ypres in Allied hands and which also projected out into the German lines. Holding the salient was a nagging strategic and tactical headache for the British. The salient was overlooked by a series of German-occupied elevated ridgelines, on which they had well-sited observation posts for guiding artillery fire onto the British positions. Some military leaders argued that holding the salient was too costly, and that the British should fall back to straighten their frontline and make it more defendable. Yet the most senior levels of British command, including General Douglas Haig, Commander-in-Chief of the BEF, and Admiral Jellicoe, the First Sea Lord, argued vociferously that no more ground could be relinquished in Flanders. To do so would run the risk of the future German offensive striking through Ypres and taking valuable Channel ports (the Germans were already in possession of ports such as Ostend and Zeebrugge), which would in turn affect Allied logistics in the northern battlefront. At the same time, the Ypres salient provided a potential jumping-off point for future Allied offensives aimed at striking through the German ridgelines and swinging north to capture the German-occupied ports, which were used as bases for the predatory U-boats. For the Germans, the need to protect those ports, plus the political and strategic incentives to hang onto large portions of Belgium, meant that they had to contain the salient or even, ideally, snuff it out.

Ypres and Flanders, therefore, were to be the locations of no fewer than five major offensive battles during the war years. (Between these battles there was an ongoing and almost continuous exchange of artillery fire over the frontlines, killing and wounding men on a daily basis and reducing the once-beautiful city of Ypres to a gutted ruin.) Some of the battles were true landmarks in military history. The Second Battle of Ypres (often given in the shorthand ‘Second Ypres’), was a powerful German effort to eradicate the salient, made more insidious by including the first major use of poison gas in warfare. The German forces unleashed chlorine gas in huge quantities, laying it onto the prevailing winds from 5,730 canisters emplaced near the frontline. Despite the fact that poison gas was strictly forbidden by Article 23 of the Hague Convention, from this point on it became a fixed element in the arsenals of both sides, delivered either by canister or (later and more commonly) by artillery shell. The offensive did not achieve its ultimate goal of taking Ypres, but the perimeter of the salient did shrink further, perilously close to the city.

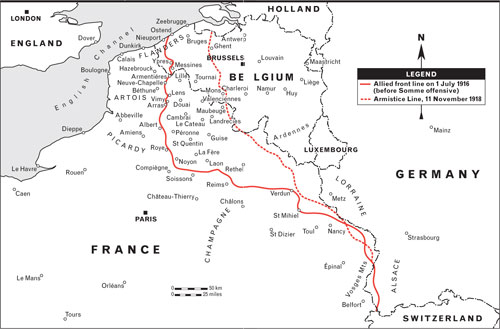

WESTERN FRONT 1914–18

DULCE ET DECORUM EST

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! – An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime …

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie;

Dulce et Decorum est

Pro patria mori

.

Wilfred Owen, 1917

Another notable offensive, this time British, was ‘Third Ypres’, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele. Conducted between 31 July and 10 November 1917, it was the attempt to break out of the salient, take the strategic ridgelines and push through the German positions to threaten the U-boat bases further north. (The offensive also served to keep pressure on the German Army at a time when the French Army was struggling with mutiny and disarray after the failed ‘Nivelle Offensive’ earlier in the year.) Third Ypres was meant to be a bold and decisive offensive, but in the event it became one of the most disastrous episodes in military history. As noted in the previous chapter, the landscape during the battle became as much as a threat as the bullets and shells, and men fought through appalling physical conditions to take landmarks that were often little more than patches of rubble surrounded by oceans of mud.