The Book of the Poppy (7 page)

Read The Book of the Poppy Online

Authors: Chris McNab

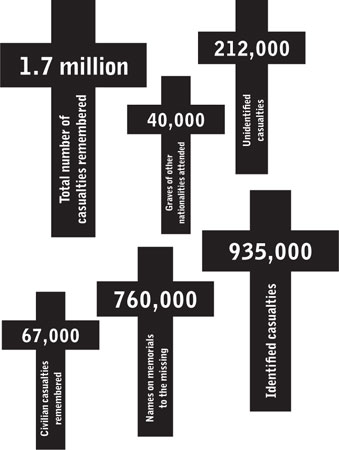

COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION – GRAVES AND MEMORIALS ATTENDED (BRITAIN AND COMMONWEALTH)

One notable aspect of these early monuments is that the focus is very much on State and imperial power, or the acts of the great commanders. The efforts and sacrifices of the humble soldier, although depicted in battle images, are largely subjugated under the greater theme of national duty. This trend continues in war memorials right up to the nineteenth century. Throughout the medieval period, wars and victories have been remembered through imposing and rather alienating statuary and monuments, such as the neoclassical Arc de Triomphe in Paris, on which are listed French victories in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars plus the names of 660 significant individuals (mostly generals) who died during the same period. In Britain (as throughout Europe), city centres are often graced with the figures of commanders on horseback or in suitable martial stance (such as Nelson’s Column) in London, and cathedrals frequently bear marble victory plaques or proudly display tattered regimental colours retrieved from the battlefield.

During the nineteenth and early twentieth century, we see the first hints of battle memorials becoming increasingly focused on the sacrifices of the rank and file. In Europe and the United States, more regimental and unit memorials were built after conflicts such as the American Civil War, Franco-Prussian War and Boer War. For example, a large memorial column was erected on Coombe Hill, near Wendover in the UK, in 1904. It was expressly focused on remembering the war dead of Buckinghamshire in the Boer War, listing their names solemnly on a memorial plaque.

It was the First World War that truly galvanised the spread of more personalised war memorials in the UK. Most of these memorials were erected after the conflict, from 1918 to about 1932. During this period, the British people were still trying to come to grips with the scale of the human loss that had befallen the nation. Furthermore, repatriation of the dead was not a standard practice during the conflict; most of the dead were buried where they fell or in improvised cemeteries near the frontline, and were later (when possible, bearing in mind the thousands of men who remained missing) disinterred and moved to concentrated war cemeteries. For millions of people back in Britain, what this meant was that they had no grave to visit. Therefore public memorials were the only tangible way to create a visible focus for their grief, and to bring the dead back into the community.

As a result, war memorials proliferated. Furthermore, Britain established rites of remembrance that would unify the nation in its loss. The first step was to set a specific day of commemoration. The natural choice was 11 November. For on that day – the eleventh day of the eleventh month – the guns fell silent on the Western Front, as the Armistice came into effect. The 1919 anniversary of this day was earmarked as Armistice Day, and it was to be both a day of remembrance plus a celebration of the victory that had been so hard won. To this day, a period of silence is observed nationally and in many countries around the world at 11 a.m. on 11 November, but the main UK day of remembrance was moved to the second Sunday in the month, known as ‘Remembrance Sunday’.

In London, the official State participation in Remembrance Sunday had a new focal point. The Cenotaph monument, set on Whitehall, was designed by the renowned architect Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens. It was initially a temporary wood and marble structure, erected for the London Victory Parade on 19 July 1919. (This was held to celebrate the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June.) After the event, the base of the memorial accrued various wreaths and tokens of remembrance, so a campaign gathered pace to keep the Cenotaph, but replace the temporary structure with a permanent stone edifice, albeit one keeping faithfully to the original design. Thus the Cenotaph was rebuilt from Portland Stone between 1919 and 1920, and this is the memorial that stands today, unveiled by King George V on 11 November 1920.

The Cenotaph has a strangely austere quality to it. Many other memorials around the UK personalise the British soldier in statuary, depicting figures of men carved or cast with astonishing attention to detail in terms of expression, kit and weaponry. The Cenotaph, by contrast, is monolithic, a huge column of stone, 35ft (11m) high and topped by the gaunt cenotaph (an empty tomb). At each end is a wreath, 5ft (1.5m) in diameter, displaying the words ‘The Glorious Dead’ below, while above are the dates of the First World War in Roman numerals (1914 – MCMXIV; 1919 – MCMXIX). Flags representing the various arms of service are displayed on either side of the monument.

Since 1919, the Cenotaph has been the focus of the National Service of Remembrance, typically attended by key members of the government and royal family, plus visiting foreign dignitaries. At first it was very much a national event, concentrating exclusively on the British war dead, a focus refreshed by the additional third of a million dead suffered during the Second World War. Yet time has changed the perspective somewhat. In 1980, it was decided that Remembrance Sunday should properly be an act of remembrance for all those who have died in conflict, regardless of their nationality or the war in which they lost their lives.

Of course, the Cenotaph is not the only national-level war memorial in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Unveiled on 12 October 2007, the Armed Forces Memorial near Lichfield in Staffordshire remembers the 16,000 British soldiers killed in conflicts post-1945. In Northern Ireland, Belfast has its own Cenotaph, set in a Garden of Remembrance. In Alexandra Gardens, Cardiff, there is the Welsh National War Memorial designed by Sir Ninian Comper and unveiled in June 1928. On the outer frieze of the colonnaded design is the Welsh inscription: I FEIBION CYMRU A RODDES EU BYWYD DROS EI GWLAD YN RHYFEL MCMXVIII, which translates as ‘To the sons of Wales who gave their lives for their country in the War 1918.’ In Scotland, the Scottish National War Memorial sits in the stunning location of Edinburgh Castle, towering over the city. Rolls of Honour inside the memorial list the names of nearly 200,000 Scottish people who died in the two world wars.

Space does not allow us here to list many of the other great memorials that stretch throughout our land. The bulk of them date from the First World War years and the 1920s–30s, as the act of war-memorial building was not as enthusiastically embraced following the Second World War. (What we often find is that the names of those killed in the Second World War are added to the monument from the previous conflict.) Each ceremony on Remembrance Sunday has its own power and conviction, yet there are some features of the service that unite the country in its reflection upon conflict.

SOME FAMOUS INTERNATIONAL WAR MEMORIALS

POWERFUL WORDS, POWERFUL SILENCE

In 1914, as the first dreadful casualty lists began to flow back to Britain from France and Belgium, the poet Robert Laurence Binyon composed a verse entitled ‘For the Fallen’, which was published in

The Times

in September. Although Binyon is likely to have been proud of the verse, he would have had little inkling at that early stage of the war how influential parts of the poem would become. In full, his poem read:

For the Fallen

With proud thanksgiving, a mother for her children,

England mourns for her dead across the sea.

Flesh of her flesh they were, spirit of her spirit,

Fallen in the cause of the free.

Solemn the drums thrill; Death august and royal

Sings sorrow up into immortal spheres.

There is music in the midst of desolation

And a glory that shines upon our tears.

They went with songs to the battle, they were young,

Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow.

They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted,

They fell with their faces to the foe.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

They mingle not with their laughing comrades again;

They sit no more at familiar tables of home;

They have no lot in our labour of the day-time;

They sleep beyond England’s foam.

But where our desires are and our hopes profound,

Felt as a well-spring that is hidden from sight,

To the innermost heart of their own land they are known

As the stars are known to the Night;

As the stars that shall be bright when we are dust,

Moving in marches upon the heavenly plain,

As the stars that are starry in the time of our darkness,

To the end, to the end, they remain.

Robert Laurence Binyon

To see the poem complete, rather than just focus on the well-known fourth stanza, brings a sense of the gulf between the attitudes to war in 1914 and those that prevailed just a few years later. The poem is undoubtedly patriotic, seeing a nobility and grandeur in conflict that had been largely purged by 1918. The soldiers advancing to meet their fates are ‘straight’, ‘true’ and ‘steady’ – any suggestion of fear is absent. And yet, there are moments of transcendent beauty in this poem, especially the fourth stanza. Such was the emotive power of this passage that it was separated from the rest of the poem to become the familiar Ode of Remembrance, still read out with solemnity at remembrance services in the UK, Australia, New Zealand and other Commonwealth nations. It is an acutely moving passage, combining eternity and mortality and a clear statement of intent by those who are alive: ‘We will remember them’. Although the overall poem from which it came does not chime well with the modern age, Binyon nevertheless left a powerful and timeless verse that is likely to endure for decades, if not centuries.

In the remembrance services, Binyon’s verse sits next to a period of two minutes’ silence, held in respect of the world’s war dead. For visitors to the UK who do not have this tradition, the experience can be moving, even startling. At 11 a.m. on 11 November (or on the following Sunday), much of the country simply stops, comes to its feet, and stands with heads bowed in silence for a period of two minutes. Businesses, schools, shopping centres, sports fixtures, government buildings – all make this unique gesture every year, a reflective break in the middle of a bustling day.

The idea of the two-minute silence was put forward by Australian journalist Edward George Honey in a letter to

The Times

in May 1919. It was embraced by the public, government and royalty, although there was initially some debate about the appropriate period for which silence had to be held. Five minutes was the initial suggestion, but this was felt to be too long, and the alternative one minute too short. Hence the two-minute silence was adopted, and on 7 November 1919, King George V declared that:

At the hour when the Armistice comes into force, the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, there may be for the brief space of two minutes a complete suspension of all our normal activities … so that in perfect stillness, the thoughts of everyone may be concentrated on reverent remembrance of the glorious dead.

THE LAST POST

‘The Last Post’ is a haunting bugle or trumpet call heard during British and Commonwealth Remembrance Day services, and at other commemorative events throughout the year. Its origins lie back in the British Army of the seventeenth century, when the call was played at the end of the day to signal that night sentries were at their posts and the day was effectively over. (‘The First Post’ signalled the start of an officer’s evening inspections.) In time, the call was incorporated into military funerals and acts of remembrance. Since 1928 it has also been played every day at 8 p.m. at the Menin Gate war memorial in Ieper (Ypres) in Belgium.