The Code Book (25 page)

Scherbius was not alone in his growing frustration. Three other inventors in three other countries had independently and almost simultaneously hit upon the idea of a cipher machine based on rotating scramblers. In the Netherlands in 1919, Alexander Koch took out patent No. 10,700, but he failed to turn his rotor machine into a commercial success and eventually sold the patent rights in 1927. In Sweden, Arvid Damm took out a similar patent, but by the time he died in 1927 he had also failed to find a market. In America, inventor Edward Hebern had complete faith in his invention, the so-called Sphinx of the Wireless, but his failure was the greatest of all.

In the mid-1920s, Hebern began building a $380,000 factory, but unfortunately this was a period when the mood in America was changing from paranoia to openness. The previous decade, in the aftermath of the First World War, the U.S. Government had established the American Black Chamber, a highly effective cipher bureau staffed by a team of twenty cryptanalysts, led by the flamboyant and brilliant Herbert Yardley. Later, Yardley wrote that “The Black Chamber, bolted, hidden, guarded, sees all, hears all. Though the blinds are drawn and the windows heavily curtained, its far-seeking eyes penetrate the secret conference chambers at Washington, Tokyo, London, Paris, Geneva, Rome. Its sensitive ears catch the faintest whisperings in the foreign capitals of the world.” The American Black Chamber solved 45,000 cryptograms in a decade, but by the time Hebern built his factory, Herbert Hoover had been elected President and was attempting to usher in a new era of trust in international affairs. He disbanded the Black Chamber, and his Secretary of State, Henry Stimson, declared that “Gentlemen should not read each other’s mail.” If a nation believes that it is wrong to read the messages of others, then it also begins to believe that others will not read its own messages, and it does not see the necessity for fancy cipher machines. Hebern sold only twelve machines at a total price of roughly $1,200, and in 1926 he was brought to trial by dissatisfied shareholders and found guilty under California’s Corporate Securities Act.

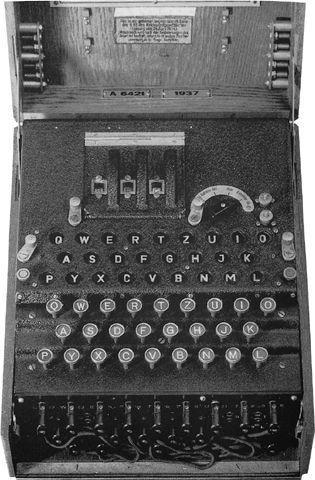

Figure 39

An army Enigma machine ready for use. (

photo credit 3.6

)

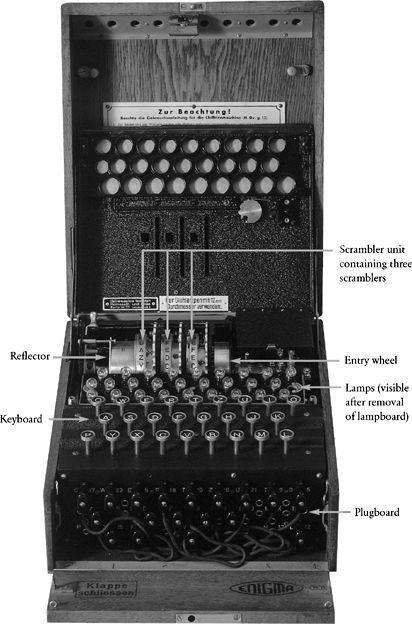

Figure 40

An Enigma machine with the inner lid opened, revealing the three scramblers.

Fortunately for Scherbius, however, the German military were eventually shocked into appreciating the value of his Enigma machine, thanks to two British documents. The first was Winston Churchill’s

The World Crisis

, published in 1923, which included a dramatic account of how the British had gained access to valuable German cryptographic material:

At the beginning of September 1914, the German light cruiser

Magdeburg

was wrecked in the Baltic. The body of a drowned German under-officer was picked up by the Russians a few hours later, and clasped in his bosom by arms rigid in death, were the cipher and signal books of the German navy and the minutely squared maps of the North Sea and Heligoland Bight. On September 6 the Russian Naval Attaché came to see me. He had received a message from Petrograd telling him what had happened, and that the Russian Admiralty with the aid of the cipher and signal books had been able to decode portions at least of the German naval messages. The Russians felt that as the leading naval Power, the British Admiralty ought to have these books and charts. If we would send a vessel to Alexandrov, the Russian officers in charge of the books would bring them to England.

This material had helped the cryptanalysts in Room 40 to crack Germany’s encrypted messages on a regular basis. Finally, almost a decade later, the Germans were made aware of this failure in their communications security. Also in 1923, the British Royal Navy published their official history of the First World War, which reiterated the fact that the interception and cryptanalysis of German communications had provided the Allies with a clear advantage. These proud achievements of British Intelligence were a stark condemnation of those responsible for German security, who then had to admit in their own report that, “the German fleet command, whose radio messages were intercepted and deciphered by the English, played so to speak with open cards against the British command.”

The German military held an enquiry into how to avoid repeating the cryptographic fiascos of the First World War, and concluded that the Enigma machine offered the best solution. By 1925 Scherbius began mass-producing Enigmas, which went into military service the following year, and were subsequently used by the government and by state-run organizations such as the railways. These Enigmas were distinct from the few machines that Scherbius had previously sold to the business community, because the scramblers had different internal wirings. Owners of a commercial Enigma machine did not therefore have a complete knowledge of the government and military versions.

Over the next two decades, the German military would buy over 30,000 Enigma machines. Scherbius’s invention provided the German military with the most secure system of cryptography in the world, and at the outbreak of the Second World War their communications were protected by an unparalleled level of encryption. At times, it seemed that the Enigma machine would play a vital role in ensuring Nazi victory, but instead it was ultimately part of Hitler’s downfall. Scherbius did not live long enough to see the successes and failures of his cipher system. In 1929, while driving a team of horses, he lost control of his carriage and crashed into a wall, dying on May 13 from internal injuries.

4 Cracking the Enigma

I

n the years that followed the First World War, the British cryptanalysts in Room 40 continued to monitor German communications. In 1926 they began to intercept messages which baffled them completely. Enigma had arrived, and as the number of Enigma machines increased, Room 40’s ability to gather intelligence diminished rapidly. The Americans and the French also tried to tackle the Enigma cipher, but their attempts were equally dismal, and they soon gave up hope of breaking it. Germany now had the most secure communications in the world.

The speed with which the Allied cryptanalysts abandoned hope of breaking Enigma was in sharp contrast to their perseverance just a decade earlier in the First World War. Confronted with the prospect of defeat, the Allied cryptanalysts had worked night and day to penetrate German ciphers. It would appear that fear was the main driving force, and that adversity is one of the foundations of successful codebreaking. Similarly, it was fear and adversity that galvanized French cryptanalysis at the end of the nineteenth century, faced with the increasing might of Germany. However, in the wake of the First World War the Allies no longer feared anybody. Germany had been crippled by defeat, the Allies were in a dominant position, and as a result they seemed to lose their cryptanalytic zeal. Allied cryptanalysts dwindled in number and deteriorated in quality.

One nation, however, could not afford to relax. After the First World War, Poland reestablished itself as an independent state, but it was concerned about threats to its newfound sovereignty. To the east lay Russia, a nation ambitious to spread its communism, and to the west lay Germany, desperate to regain territory ceded to Poland after the war. Sandwiched between these two enemies, the Poles were desperate for intelligence information, and they formed a new cipher bureau, the Biuro Szyfrów. If necessity is the mother of invention, then perhaps adversity is the mother of cryptanalysis. The success of the Biuro Szyfrów is exemplified by their success during the Russo-Polish War of 1919–20. In August 1920 alone, when the Soviet armies were at the gates of Warsaw, the Biuro deciphered 400 enemy messages. Their monitoring of German communications had been equally effective, until 1926, when they too encountered the Enigma messages.

In charge of deciphering German messages was Captain Maksymilian Ciezki, a committed patriot who had grown up in the town of Szamotuty, a center of Polish nationalism. Ciezki had access to a commercial version of the Enigma machine, which revealed all the principles of Scherbius’s invention. Unfortunately, the commercial version was distinctly different from the military one in terms of the wirings inside each scrambler. Without knowing the wirings of the military machine, Ciezki had no chance of deciphering messages being sent by the German army. He became so despondent that at one point he even employed a clairvoyant in a frantic attempt to conjure some sense from the enciphered intercepts. Not surprisingly, the clairvoyant failed to make the breakthrough the Biuro Szyfrów needed. Instead, it was left to a disaffected German, Hans-Thilo Schmidt, to make the first step toward breaking the Enigma cipher.

Hans-Thilo Schmidt was born in 1888 in Berlin, the second son of a distinguished professor and his aristocratic wife. Schmidt embarked on a career in the German Army and fought in the First World War, but he was not considered worthy enough to remain in the army after the drastic cuts implemented as part of the Treaty of Versailles. He then tried to make his name as a businessman, but his soap factory was forced to close because of the postwar depression and hyperinflation, leaving him and his family destitute.

The humiliation of Schmidt’s failures was compounded by the success of his elder brother, Rudolph, who had also fought in the war, and who was retained in the army afterward. During the 1920s Rudolph rose through the ranks and was eventually promoted to chief of staff of the Signal Corps. He was responsible for ensuring secure communications, and in fact it was Rudolph who officially sanctioned the army’s use of the Enigma cipher.

After his business collapsed, Hans-Thilo was forced to ask his brother for help, and Rudolph arranged a job for him in Berlin at the Chiffrierstelle, the office responsible for administrating Germany’s encrypted communications. This was Enigma’s command center, a top-secret establishment dealing with highly sensitive information. When Hans-Thilo moved to his new job, he left his family behind in Bavaria, where the cost of living was affordable. He was living alone in expensive Berlin, impoverished and isolated, envious of his perfect brother and resentful toward a nation which had rejected him. The result was inevitable. By selling secret Enigma information to foreign powers, Hans-Thilo Schmidt could earn money and gain revenge, damaging his country’s security and undermining his brother’s organization.

On November 8, 1931, Schmidt arrived at the Grand Hotel in Verviers, Belgium, for a liaison with a French secret agent codenamed Rex. In exchange for 10,000 marks (equivalent to $30,000 in today’s money), Schmidt allowed Rex to photograph two documents: “Gebrauchsanweisung für die Chiffriermaschine Enigma” and “Schlüsselanleitung für die Chiffriermaschine Enigma.” These documents were essentially instructions for using the Enigma machine, and although there was no explicit description of the wirings inside each scrambler, they contained the information needed to deduce those wirings.

Figure 41

Hans-Thilo Schmidt. (

photo credit 4.1

)

Thanks to Schmidt’s treachery, it was now possible for the Allies to create an accurate replica of the German military Enigma machine. However, this was not enough to enable them to decipher messages encrypted by Enigma. The strength of the cipher depends not on keeping the machine secret, but on keeping the initial setting of the machine (the key) secret. If a cryptanalyst wants to decipher an intercepted message, then, in addition to having a replica of the Enigma machine, he still has to find which of the millions of billions of possible keys was used to encipher it. A German memorandum put it thus: “It is assumed in judging the security of the cryptosystem that the enemy has at his disposition the machine.”