The Code Book (27 page)

Figure 42

Marian Rejewski.

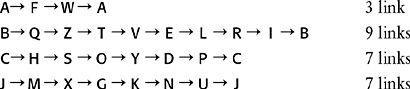

Rejewski had no idea of the day key, and he had no idea which message keys were being chosen, but he did know that they resulted in this table of relationships. Had the day key been different, then the table of relationships would have been completely different. The next question was whether there existed any way of determining the day key by looking at the table of relationships. Rejewski began to look for patterns within the table, structures that might indicate the day key. Eventually, he began to study one particular type of pattern, which featured chains of letters. For example, in the table, A on the top row is linked to F on the bottom row, so next he would look up F on the top row. It turns out that F is linked to W, and so he would look up W on the top row. And it turns out that W is linked to A, which is where we started. The chain has been completed.

With the remaining letters in the alphabet, Rejewski would generate more chains. He listed all the chains, and noted the number of links in each one:

So far, we have only considered the links between the 1st and 4th letters of the six-letter repeated key. In fact, Rejewski would repeat this whole exercise for the relationships between the 2nd and 5th letters, and the 3rd and 6th letters, identifying the chains in each case and the number of links in each chain.

Rejewski noticed that the chains changed each day. Sometimes there were lots of short chains, sometimes just a few long chains. And, of course, the letters within the chains changed. The characteristics of the chains were clearly a result of the day key setting-a complex consequence of the plugboard settings, the scrambler arrangement and the scrambler orientations. However, there remained the question of how Rejewski could determine the day key from these chains. Which of 10,000,000,000,000,000 possible day keys was related to a particular pattern of chains? The number of possibilities was simply too great.

It was at this point that Rejewski had a profound insight. Although the plugboard and scrambler settings both affect the details of the chains, their contributions can to some extent be disentangled. In particular, there is one aspect of the chains which is wholly dependent on the scrambler settings, and which has nothing to do with the plugboard settings: the numbers of links in the chains is purely a consequence of the scrambler settings. For instance, let us take the example above and pretend that the day key required the letters S and G to be swapped as part of the plugboard settings. If we change this element of the day key, by removing the cable that swaps S and G, and use it to swap, say, T and K instead, then the chains would change to the following:

Some of the letters in the chains have changed, but, crucially, the number of links in each chain remains constant. Rejewski had identified a facet of the chains that was solely a reflection of the scrambler settings.

The total number of scrambler settings is the number of scrambler arrangements (6) multiplied by the number of scrambler orientations (17,576) which comes to 105,456. So, instead of having to worry about which of the 10,000,000,000,000,000 day keys was associated with a particular set of chains, Rejewski could busy himself with a drastically simpler problem: which of the 105,456 scrambler settings was associated with the numbers of links within a set of chains? This number is still large, but it is roughly one hundred billion times smaller than the total number of possible day keys. In short, the task has become one hundred billion times easier, certainly within the realm of human endeavor.

Rejewski proceeded as follows. Thanks to Hans-Thilo Schmidt’s espionage, he had access to replica Enigma machines. His team began the laborious chore of checking each of 105,456 scrambler settings, and cataloguing the chain lengths that were generated by each one. It took an entire year to complete the catalogue, but once the Biuro had accumulated the data, Rejewski could finally begin to unravel the Enigma cipher.

Each day, he would look at the encrypted message keys, the first six letters of all the intercepted messages, and use the information to build his table of relationships. This would allow him to trace the chains, and establish the number of links in each chain. For example, analyzing the 1st and 4th letters might result in four chains with 3, 9, 7 and 7 links. Analyzing the 2nd and 5th letters might also result in four chains, with 2, 3, 9 and 12 links. Analyzing the 3rd and 6th letters might result in five chains with 5, 5, 5, 3 and 8 links. As yet, Rejewski still had no idea of the day key, but he knew that it resulted in 3 sets of chains with the following number of chains and links in each one:

4 chains from the 1st and 4th letters, with 3, 9, 7 and 7 links.

4 chains from the 2nd and 5th letters, with 2, 3, 9 and 12 links.

5 chains from the 3rd and 6th letters, with 5, 5, 5, 3 and 8 links.

Rejewski could now go to his catalogue, which contained every scrambler setting indexed according to the sort of chains it would generate. Having found the catalogue entry that contained the right number of chains with the appropriate number of links in each one, he immediately knew the scrambler settings for that particular day key. The chains were effectively fingerprints, the evidence that betrayed the initial scrambler arrangement and orientations. Rejewski was working just like a detective who might find a fingerprint at the scene of a crime, and then use a database to match it to a suspect.

Although he had identified the scrambler part of the day key, Rejewski still had to establish the plugboard settings. Although there are about a hundred billion possibilities for the plugboard settings, this was a relatively straightforward task. Rejewski would begin by setting the scramblers in his Enigma replica according to the newly established scrambler part of the day key. He would then remove all cables from the plugboard, so that the plugboard had no effect. Finally, he would take a piece of intercepted ciphertext and type it in to the Enigma machine. This would largely result in gibberish, because the plugboard cablings were unknown and missing. However, every so often vaguely recognizable phrases would appear, such as alliveinbelrin—presumably, this should be “arrive in Berlin.” If this assumption is correct, then it would imply that the letters R and L should be connected and swapped by a plugboard cable, while A, I, V, E, B and N should not. By analyzing other phrases it would be possible to identify the other five pairs of letters that had been swapped by the plugboard. Having established the plugboard settings, and having already discovered the scrambler settings, Rejewski had the complete day key, and could then decipher any message sent that day.

Rejewski had vastly simplified the task of finding the day key by divorcing the problem of finding the scrambler settings from the problem of finding the plugboard settings. On their own, both of these problems were solvable. Originally, we estimated that it would take more than the lifetime of the universe to check every possible Enigma key. However, Rejewski had spent only a year compiling his catalogue of chain lengths, and thereafter he could find the day key before the day was out. Once he had the day key, he possessed the same information as the intended receiver and so could decipher messages just as easily.

Following Rejewski’s breakthrough, German communications became transparent. Poland was not at war with Germany, but there was a threat of invasion, and Polish relief at conquering Enigma was nevertheless immense. If they could find out what the German generals had in mind for them, there was a chance that they could defend themselves. The fate of the Polish nation had depended on Rejewski, and he did not disappoint his country. Rejewski’s attack on Enigma is one of the truly great accomplishments of cryptanalysis. I have had to sum up his work in just a few pages, and so have omitted many of the technical details, and all of the dead ends. Enigma is a complicated cipher machine, and breaking it required immense intellectual force. My simplifications should not mislead you into underestimating Rejewski’s extraordinary achievement.

The Polish success in breaking the Enigma cipher can be attributed to three factors: fear, mathematics and espionage. Without the fear of invasion, the Poles would have been discouraged by the apparent invulnerability of the Enigma cipher. Without mathematics, Rejewski would not have been able to analyze the chains. And without Schmidt, codenamed “Asche,” and his documents, the wirings of the scramblers would not have been known, and cryptanalysis could not even have begun. Rejewski did not hesitate to express the debt he owed Schmidt: “Asche’s documents were welcomed like manna from heaven, and all doors were immediately opened.”

The Poles successfully used Rejewski’s technique for several years. When Hermann Göring visited Warsaw in 1934, he was totally unaware of the fact that his communications were being intercepted and deciphered. As he and other German dignitaries laid a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier next to the offices of the Biuro Szyfrów, Rejewski could stare down at them from his window, content in the knowledge that he could read their most secret communications.

Even when the Germans made a minor alteration to the way they transmitted messages, Rejewski fought back. His old catalogue of chain lengths was useless, but rather than rewriting the catalogue he devised a mechanized version of his cataloguing system, which could automatically search for the correct scrambler settings. Rejewski’s invention was an adaptation of the Enigma machine, able to rapidly check each of the 17,576 settings until it spotted a match. Because of the six possible scrambler arrangements, it was necessary to have six of Rejewski’s machines working in parallel, each one representing one of the possible arrangements. Together, they formed a unit that was about a meter high, capable of finding the day key in roughly two hours. The units were called

bombes

, a name that might reflect the ticking noise they made while checking scrambler settings. Alternatively, it is said that Rejewski got his inspiration for the machines while at a cafe eating a

bombe

, an ice cream shaped into a hemisphere. The bombes effectively mechanized the process of decipherment. It was a natural response to Enigma, which was a mechanization of encipherment.

For most of the 1930s, Rejewski and his colleagues worked tirelessly to uncover the Enigma keys. Month after month, the team would have to deal with the stresses and strains of cryptanalysis, continually having to fix mechanical failures in the bombes, continually having to deal with the never-ending supply of encrypted intercepts. Their lives became dominated by the pursuit of the day key, that vital piece of information that would reveal the meaning of the encrypted messages. However, unknown to the Polish codebreakers, much of their work was unnecessary. The chief of the Biuro, Major Gwido Langer, already had the Enigma day keys, but he kept them hidden, tucked away in his desk.

Langer, via the French, was still receiving information from Schmidt. The German spy’s nefarious activities did not end in 1931 with the delivery of the two documents on the operation of Enigma, but continued for another seven years. He met the French secret agent Rex on twenty occasions, often in secluded alpine chalets where privacy was guaranteed. At every meeting, Schmidt handed over one or more codebooks, each one containing a month’s worth of day keys. These were the codebooks that were distributed to all German Enigma operators, and they contained all the information that was needed to encipher and decipher messages. In total, he provided codebooks that contained 38 months’ worth of day keys. The keys would have saved Rejewski an enormous amount of time and effort, shortcutting the necessity for bombes and sparing manpower that could have been used in other sections of the Biuro. However, the remarkably astute Langer decided not to tell Rejewski that the keys existed. By depriving Rejewski of the keys, Langer believed he was preparing him for the inevitable time when the keys would no longer be available. He knew that if war broke out it would be impossible for Schmidt to continue to attend covert meetings, and Rejewski would then be forced to be self-sufficient. Langer thought that Rejewski should practice self-sufficiency in peacetime, as preparation for what lay ahead.