The Complete Yes Minister (29 page)

[

Hacker’s diary continues – Ed

.]

Hacker’s diary continues – Ed

.]

March 25th

Today I paid an official visit to St Edward’s Hospital. It was a real eye-opener.

The Welcoming Committee – I use the term in the very broadest sense, because I can hardly imagine a group of people who were less welcoming – were lined up on the steps.

I met Mrs Rogers, the Chief Administrator, and an appalling Glaswegian called Billy Fraser who rejoices in the title of Chairman of the Joint Shop Stewards Negotiating Committee. Mrs Rogers was about forty-five. Very slim, dark hair with a grey streak – a very handsome Hampstead lady who speaks with marbles in her mouth.

‘How very nice to meet you,’ I said to Fraser, offering to shake his hand.

‘I wouldn’t count on it,’ he snarled.

I was shown several empty wards, several administrative offices that were veritable hives of activity, and finally a huge deserted dusty operating theatre suite. I enquired about the cost of it. Mrs Rogers informed me that, together with Radiotherapy and Intensive Care, it cost two and a quarter million pounds.

I asked her if she was not horrified that the place was not in use.

‘No,’ she said cheerfully. ‘Very good thing in some ways. Prolongs its life. Cuts down running costs.’

‘But there are no patients,’ I reminded her.

She agreed. ‘Nonetheless,’ she added, ‘the essential work of the hospital has to go on.’

‘I thought the patients were the essential work of the hospital.’

‘Running an organisation of five hundred people is a big job, Minister,’ said Mrs Rogers, beginning to sound impatient with me.

‘Yes,’ I spluttered, ‘but if they weren’t here they wouldn’t be here.’

‘What?’

Obviously she wasn’t getting my drift. She has a completely closed mind.

I decided that it was time to be decisive. I told her that this situation could not continue. Either she got patients into the hospital, or I closed it.

She started wittering. ‘Yes, well, Minister, in the course of time I’m sure . . .’

‘Not in the course of time,’ I said.

‘Now

. We will get rid of three hundred of your people and use the savings to pay for some doctors and nurses so that we can get some patients in.’

‘Now

. We will get rid of three hundred of your people and use the savings to pay for some doctors and nurses so that we can get some patients in.’

Billy Fraser then started to put in his two penn’orth.

‘Look here,’ he began, ‘without those two hundred people this hospital just wouldn’t function.’

‘Do you think it’s functioning now?’ I enquired.

Mrs Rogers was unshakeable in her self-righteousness. ‘It is one of the best-run hospitals in the country,’ she said. ‘It’s up for the Florence Nightingale award.’

I asked what that was, pray.

‘It’s won,’ she told me proudly, ‘by the most hygienic hospital in the Region.’

I asked God silently to give me strength. Then I told her that I’d said my last word and that three hundred staff must go, doctors and nurses hired, and patients admitted.

‘You mean, three hundred jobs lost?’ Billy Fraser’s razor-sharp brain had finally got the point.

Mrs Rogers had already got the point. But Mrs Rogers clearly felt that this hospital had no need of patients. She said that in any case they couldn’t do any serious surgery with just a skeleton medical staff. I told her that I didn’t care whether or not she did serious surgery – she could do nothing but varicose veins, hernias and piles for all I cared. But

something

must be done.

something

must be done.

‘Do you mean three hundred jobs lost,’ said Billy Fraser angrily, still apparently seeking elucidation of the simple point everybody else had grasped ten minutes ago.

I spelt it out to him. ‘Yes I do, Mr Fraser,’ I replied. ‘A hospital is not a source of employment, it is a place to heal the sick.’

He was livid. His horrible wispy beard was covered in spittle as he started to shout abuse at me, his little pink eyes blazing with class hatred and alcohol. ‘It’s a source of employment for my members,’ he yelled. ‘You want to put them out of work, do you, you bastard?’ he screamed. ‘Is that what you call a compassionate society?’

I was proud of myself. I stayed calm. ‘Yes,’ I answered coolly. ‘I’d rather be compassionate to the patients than to your members.’

‘We’ll come out on strike,’ he yelled.

I couldn’t believe my eyes or ears. I was utterly delighted with that threat. I laughed in his face.

‘Fine,’ I said happily. ‘Do that. What does it matter? Who can you harm? Please, do go on strike, the sooner the better. And take all those administrators with you,’ I added, waving in the direction of the good Mrs Rogers. ‘Then we won’t have to pay you.’

Bernard and I left the battlefield of St Edward’s Hospital, I felt, as the undisputed victors of the day.

It’s very rare in politics that one has the pleasure of completely wiping the floor with one’s opponents. It’s a good feeling.

March 26th

It seems I didn’t quite wipe the floor after all. The whole picture changed in a most surprising fashion.

Bernard and I were sitting in the office late this afternoon congratulating ourselves on yesterday’s successes. I was saying, rather smugly I fear, that Billy Fraser’s strike threat had played right into my hands.

We turned on the television news. First there was an item saying that the British Government is again being pressured by the US Government to take some more Cuban refugees. And then – the bombshell! Billy Fraser came on, and threatened that the whole of the NHS in London would be going on strike tonight at midnight if we laid off workers at St Edward’s. I was shattered.

[

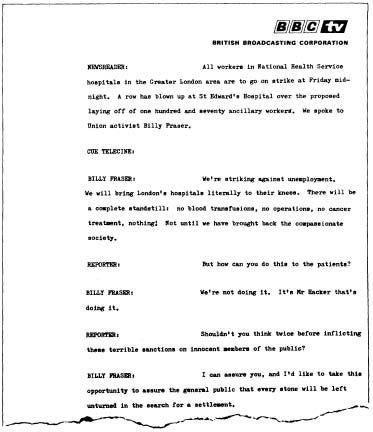

We have been fortunate to obtain the transcript of the television news programme in question, and it is reproduced below – Ed

.]

We have been fortunate to obtain the transcript of the television news programme in question, and it is reproduced below – Ed

.]

Humphrey came in at that moment.

‘Oh,’ he said, ‘you’re watching it.’

‘Yes,’ I said through clenched teeth. ‘Humphrey, you told me you were going to have a word with the unions.’

‘I did,’ he replied. ‘But well, what can I do?’ He shrugged helplessly. I’m sure he did his best with the unions. But where has it got us?

I asked him what we were supposed to do now.

But Humphrey had come, apparently, on a different matter – of equal urgency. Another bombshell, in fact!

‘It looks as if Sir Maurice Williams’ independent enquiry is going to be unfavourable to us,’ he began.

I was appalled. Humphrey had promised me that Williams was sound. He had told me that the man wanted a peerage.

‘Unfortunately,’ murmured Sir Humphrey, embarrassed, looking at his shoes, ‘he’s also trying to work his peerage in his capacity as Chairman of the Joint Committee for the Resettlement of Refugees.’

I enquired if there were more Brownie points in refugees than in government enquiries.

He nodded.

I pointed out that we simply haven’t got the money to house any more refugees.

Then came bombshell number three! The phone rang. It was Number Ten.

I got on the line. I was told rather sharply by a senior policy adviser that Number Ten had seen Billy Fraser on the six o’clock news. By ‘Number Ten’ he meant the PM. Number Ten hoped a peace formula could be found very soon.

As I was contemplating this euphemistic but heavy threat from Downing Street, Humphrey was still rattling on about the boring old Cuban refugees. Sir Maurice would be satisfied if we just housed a thousand of them, he said.

As I was about to explain, yet again, that we haven’t the time or the money to open a thousand-bed hostel . . . the penny dropped!

A most beautiful solution had occurred to me.

A thousand refugees with nowhere to go. A thousand-bed hospital, fully staffed. Luck was on our side after all. The symmetry was indescribably lovely.

Humphrey saw what I was thinking, of course, and seemed all set to resist. ‘Minister,’ he began, ‘that hospital has millions of pounds’ worth of high-technology equipment. It was built for sick British, not healthy foreigners. There is a huge Health Service waiting list. It would be an act of the most appalling financial irresponsibility to waste all that investment on . . .’

I interrupted this flow of hypocritical jingoistic nonsense.

‘But . . .’ I said carefully, ‘what about the independent enquiry? Into our Department? Didn’t you say that Sir Maurice’s enquiry was going to come down against us? Is that what you want?’

He paused. ‘I see your point, Minister,’ he replied thoughtfully.

I told Bernard to reinstate, immediately, all the staff at St Edward’s, to tell Sir Maurice we are making a brand-new hospital available to accommodate a thousand refugees, and to tell the press it was my decision. Everyone was going to be happy!

Bernard asked me for a quote for the press release. A good notion.

‘Tell them,’ I said, ‘that Mr Hacker said that this was a tough decision but a necessary one, if we in Britain aim to be worthy of the name of . . . the compassionate society.’

I asked Humphrey if he was agreeable to all this.

‘Yes Minister,’ he said. And I thought I detected a touch of admiration in his tone.

1

The 800 people with the rank of Under-Secretary and above.

The 800 people with the rank of Under-Secretary and above.

2

A sign of growing awareness here from Hacker.

A sign of growing awareness here from Hacker.

3

Meaning without respect.

Meaning without respect.

9

The Death List

March 28th

It’s become clear to me, as I sit here for my usual Sunday evening period of contemplation and reflection, that Roy (my driver) knows a great deal more than I realised about what is going on in Whitehall.

Whitehall is the most secretive square mile in the world. The great emphasis on avoidance of error (which is what the Civil Service is really about, since that is their only real incentive) also means that avoidance of publication is equally necessary.

As Sir Arnold is reported to have said some months ago, ‘If no one knows what you’re doing, then no one knows what you’re doing

wrong

.’

wrong

.’

[

Perhaps this explains why government forms are always so hard to understand. Forms are written to protect the person who is in charge of the form – Ed

.]

Perhaps this explains why government forms are always so hard to understand. Forms are written to protect the person who is in charge of the form – Ed

.]

And so the way information is provided – or withheld – is the key to running the government smoothly.

This concern with the avoidance of error leads inexorably to the need to commit everything to paper – civil servants copy

everything

, and send copies to all their colleagues. (This is also because ‘chaps don’t like to leave other chaps out’, as Bernard once explained to me.) The Treasury was rather more competent before the invention of Xerox than it is now, because its officials had so much less to read (and therefore less to confuse them).

everything

, and send copies to all their colleagues. (This is also because ‘chaps don’t like to leave other chaps out’, as Bernard once explained to me.) The Treasury was rather more competent before the invention of Xerox than it is now, because its officials had so much less to read (and therefore less to confuse them).

The civil servants’ hunger for paper is insatiable. They want all possible information sent to them, and they send all possible information to their colleagues. It amazes me that they find the time to do anything other than catch up with other people’s paperwork. If indeed they do.

It is also astonishing that so little of this vast mass of typescript ever becomes public knowledge – a very real tribute to Whitehall’s talent for secrecy. For it is axiomatic with civil servants that information should only be revealed to their political ‘masters’ when absolutely necessary, and to the public when absolutely unavoidable.

But I now see that I can learn some useful lessons from their methods. For a start, I must pay more attention to Bernard and Roy. I resolve today that I will not let false pride come between Roy and me – in other words, I shall no longer pretend that I know more than my driver does. Tomorrow, when he collects me at Euston, I shall ask him to tell me anything that he has picked up, and I shall tell him that he mustn’t assume that Ministers know more secrets than drivers.

On second thoughts, I don’t need to tell him that – he knows already!

As to the Private Secretaries’ grapevine, it was most interesting to learn last week that Sir Humphrey had had a wigging from Sir Arnold. This will have profoundly upset Humphrey, who above all values the opinions of his colleagues.

For there is one grapevine with even more knowledge and influence than the Private Secretaries’ or the drivers’ – and that is the Permanent Secretaries’ grapevine. (Cabinet colleagues, of course, have a hopeless grapevine because they are not personal friends, don’t know each other all that well, and hardly ever see each other except in Cabinet or in the Division Lobby.)

This wigging could also, I gather, affect his chances of becoming Secretary to the Cabinet on Arnold’s retirement, or screw up the possibility of his finding a cushy job in Brussels.

Happily, this is not my problem – and, when I mentioned it to my spies, both Bernard and Roy agreed (independently) that Sir Humphrey would not be left destitute. Apart from his massive indexlinked pension, a former Permanent Secretary is always fixed up with a job if he wants it – Canals and Waterways, or

something

.

something

.

Other books

Seeker of Stars: A Novel by Fish, Susan

Power Play by Lynn, Tara

The Sword of Aldones by Marion Zimmer Bradley

Death of a Citizen by Donald Hamilton

Journeys with My Mother by Halina Rubin

Spirit Wolf by Gary D. Svee

Dark Places by Gillian Flynn

Death Blows: The Bloodhound Files-2 by DD Barant

London Noir by Cathi Unsworth

The Painting by Ryan Casey