The Complete Yes Minister (32 page)

Sir Humphrey was now as baffled as I.

‘I don’t know how I can express it more clearly, Minister,’ he said plaintively.

Obviously, I wanted him to explain things like what the list was, where it came from, why I was on it – my mind was racing with dozens of unanswered questions, that’s why I was so inarticulate.

Sir Humphrey tried to answer what he thought I was asking him.

‘To put it absolutely bluntly, Minister, confidential investigations have revealed the existence of certain documents whose provenance is currently unestablished, but whose effect if realised would be to create a cabinet vacancy and precipitate a by-election.’

I didn’t know what he meant. I asked him.

‘You are on a death list, Minister.’

We were going round in circles. ‘Who . . . ?’ I spluttered, ‘What . . . ?’

‘Ah,’ he said. ‘I see. It is the International Freedom Army. A new urban guerrilla group, apparently.’

My bowels were turning to water. ‘But what have they got against me?’ I whispered.

Bernard reminded me of the vague rumours recently of a Cabinet reshuffle, and that my name has been mentioned in one or two of the papers in connection with the Ministry of Defence.

I asked who they could be, these urban guerrillas. Bernard and Humphrey just shrugged.

‘Hard to say, Minister. It could be an Irish splinter group, or Baader-Meinhof, or PLO, or Black September. It could be home-grown loonies – Anarchists, Maoists. Or it might be Libyans, Iranians, or the Italian Red Brigade for all we know.’

‘In any case,’ added Bernard, ‘they’re all interconnected really. This could simply be a new group of freelance killers. The Special Branch don’t know where to start.’

That was

very

encouraging, I must say! I couldn’t get over the cool, callous, unemotional way in which they were discussing some maniacs who were trying to kill me.

very

encouraging, I must say! I couldn’t get over the cool, callous, unemotional way in which they were discussing some maniacs who were trying to kill me.

I tried to grasp at straws.

‘There’s a

list

of names, is there? You said a list? Not just me?’

list

of names, is there? You said a list? Not just me?’

‘Not just you, Minister,’ Sir Humphrey confirmed.

I said that I supposed that there were hundreds of names on it.

‘Just three,’ said Humphrey.

‘Three?’

I was in a state of shock. I think. Or panic. One of those. I just sat there unable to think or speak. My mouth had completely dried up.

As I tried to say something, anything, the phone rang. Bernard answered it. Apparently somebody called Commander Forest from Special Branch had come to brief me.

Bernard went to get him. As he left he turned to me and said in a kindly fashion: ‘Try looking at it this way, Minister – it’s always nice to be on a shortlist. At least they know who you are.’

I gave him a withering look, and he hurried out.

Sir Humphrey filled in the background. The Special Branch had apparently informed the Home Secretary (the usual procedure) who recommended detectives to protect me.

I don’t see how they can protect me. How can detectives protect me from an assassin’s bullet? Nobody can. Everybody knows that.

I said this to Humphrey. I suppose I hoped he’d disagree – but he didn’t. ‘Look at it this way,’ he responded. ‘Even if detectives cannot protect anyone, they do ensure that the assassin is brought to justice. After the victim has been gunned down.’

Thanks a lot!

Bernard brought in Commander Forest. He was a tall thin cadaverous-looking individual, with a slightly nervous flinching manner. He didn’t really inspire confidence.

I decided that I had to put on a brave show. Chin up, stiff upper lip, pull myself together, that sort of thing. I’d been talking a lot about leadership. Now I had to prove to them – and myself – that I was officer material.

I smiled reassuringly at the Commander, as he offered to brief me on the standard hazards and routine precautions. ‘I don’t really have to take these things too seriously, do I?’ I asked in a cavalier manner.

‘Well, sir, in a sense, it’s up to you, but we do

advise

. . .’

advise

. . .’

I interrupted. ‘Look, I can see that some people might get into a frightful funk but, well, it’s the job, isn’t it? All in a day’s work.’

Commander Forest gazed at me strangely. ‘I admire your courage, sir,’ he said as if he really thought I were a raving idiot.

I decided I’d done enough of the stiff upper lip. I’d let him speak. ‘Okay, shoot,’ I said. It was an unfortunate turn of phrase.

‘Read this,’ he said, and thrust a Xeroxed typescript into my hand. ‘This will tell you all you need to know. Study it, memorise it, and keep it to yourself.’

[

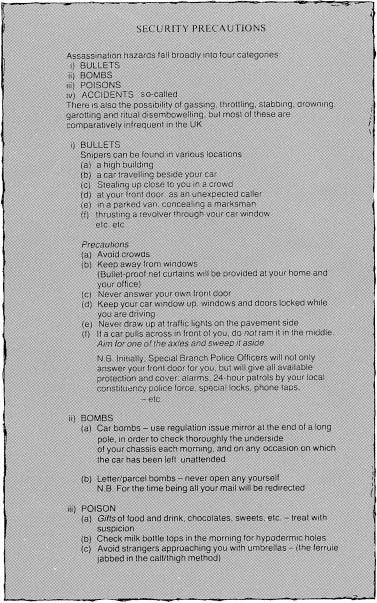

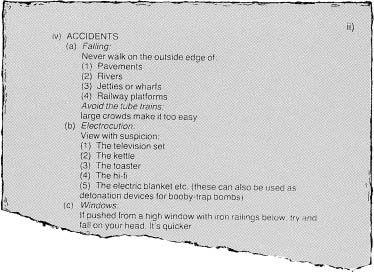

The Museum of the Metropolitan Police at New Scotland Yard has kindly lent us a copy of ‘Security Precautions’, the document handed to Hacker. It is self-explanatory – Ed

.]

The Museum of the Metropolitan Police at New Scotland Yard has kindly lent us a copy of ‘Security Precautions’, the document handed to Hacker. It is self-explanatory – Ed

.]

I read the document through. It seemed to me as though I had little chance of survival. But I must continue to have courage.

After Commander Forest had left, I asked Humphrey how the police would find these terrorists before they found me. That seems to be my only hope.

Sir Humphrey remarked that telephone tapping and electronic surveillance of all possible suspects is the best way of picking these bastards up.

‘But,’ he added cautiously, ‘that does incur intolerable intrusion upon individual privacy.’

I carefully considered the implications of this comment.

And then I came to the conclusion. A slightly different conclusion, although I think that perhaps he had misunderstood what I’d been saying earlier.

I explained that, on the other hand, if the people’s elected representatives are to represent the people, it follows that any attack on these elected representatives is,

in itself

, an attack on freedom and democracy. The reason is clear. Such threats strike at the very heart of the people’s inalienable democratic right to be governed by the leaders of their choice. Therefore, the safety of these leaders must be protected by every possible means – however much we might regret the necessity for doing so or the measures that we may be forced to take.

in itself

, an attack on freedom and democracy. The reason is clear. Such threats strike at the very heart of the people’s inalienable democratic right to be governed by the leaders of their choice. Therefore, the safety of these leaders must be protected by every possible means – however much we might regret the necessity for doing so or the measures that we may be forced to take.

I explained all this to Humphrey. He was in complete agreement – although I didn’t care for his choice of words. ‘Beautifully argued, Minister,’ he replied. ‘My view exactly – or else you’re a dead duck.’

April 5th

Today there was a slight embarrassment.

My petition arrived.

The petition against phone tapping and electronic surveillance, the one that I started a year and a half ago when I was in opposition and Editor of

Reform

. Bernard wheeled into the office a huge office trolley loaded with piles of exercise books and reams of paper. It now has two and a quarter million signatures. A triumph of organisation and commitment, and what the hell do I bloody well do with it?

Reform

. Bernard wheeled into the office a huge office trolley loaded with piles of exercise books and reams of paper. It now has two and a quarter million signatures. A triumph of organisation and commitment, and what the hell do I bloody well do with it?

It is now clear to me – now that I have the

full

facts which you cannot get when in opposition, of course – that surveillance is an indispensable weapon in the fight against organised terror and crime.

full

facts which you cannot get when in opposition, of course – that surveillance is an indispensable weapon in the fight against organised terror and crime.

Bernard understood. He offered to file the petition.

I wasn’t sure that filing it was the answer. We had acknowledged receipt from the deputation – they would never ask to see it again. And they would imagine that it was in safe hands since I’m the one who began it all.

I told him to shred it. ‘Bernard,’ I said, ‘we must make certain that no one ever finds it again.’

‘In that case,’ replied Bernard, ‘I’m sure it would be best to file it.’

[

This situation was not without precedent

.

This situation was not without precedent

.

In April 1965 the Home Secretary told the House of Commons that ‘no useful purpose’ would be served by reopening the enquiry into the Timothy Evans case. This was despite a passionate appeal from a leading member of the Opposition front bench, Sir Frank Soskice, who said: ‘My appeal to the Home Secretary is most earnest. I believe that if ever there was a debt due to justice and to the reputation both of our own judicial system and to the public conscience . . . that debt is one the Home Secretary should now repay.’

Interestingly enough, a general election had occurred between the launching and the presenting of the petition. Consequently the Home Secretary who rejected Sir Frank Soskice’s impassioned appeal – and petition – for an enquiry was Sir Frank Soskice – Ed

.]

.]

April 11th

I’ve just had the most awful Easter weekend of my life.

Annie and I went off on our quiet little weekend together just like we used to.

Well – almost like we used to. Unfortunately, half the Special Branch came with us.

When we went for a quiet afternoon stroll through the woods, the whole place was swarming with rozzers.

They kept nice and close to us – very protective, but impossible for Annie and me to discuss anything but the weather. They all look the other way –

not

, I hasten to add, out of courtesy or respect for our privacy, but to see if they could spot any potential attacker leaping towards me over the primroses.

not

, I hasten to add, out of courtesy or respect for our privacy, but to see if they could spot any potential attacker leaping towards me over the primroses.

We went to a charming restaurant for lunch. It seemed as though the whole of Scotland Yard came too.

‘How many for lunch?’ asked the head waiter as we came in.

‘Nine,’ said Annie acidly. The weekend was not working out as she’d expected.

The head waiter offered us a nice table for two by the window, but it was vetoed by a sergeant. ‘No, that’s not safe,’ he muttered to me, and turned to a colleague, ‘we’ve chosen that table over there for the target.’

Target!

So Annie and I were escorted to a cramped little table in a poky little corner next to the kitchen doors. They banged open and shut right beside us, throughout our meal.

As we sat down I was briefed by one of the detectives. ‘You sit here. Constable Ross will sit over there, watching the kitchen door – that’s your escape route. We don’t

expect

any assassins to be among the kitchen staff as we only booked in here late morning. I’ll sit by the window. And if you do hear any gunshots, just dive under the table and I’ll take care of it.’

expect

any assassins to be among the kitchen staff as we only booked in here late morning. I’ll sit by the window. And if you do hear any gunshots, just dive under the table and I’ll take care of it.’

I’m sure he meant to be reassuring.

I informed him that I wasn’t a bit worried. Then I heard a loud report close to my head, and I crashed under the table.

An utterly humiliating experience – some seconds later I stuck my head out and realised that a champagne bottle had just been opened for the next table. I had to pretend that I’d just been practising.

By this time, with all this talk of escape routes, assassins in the kitchen and so forth, I’d gone right off my food. So had Annie. And our appetites weren’t helped by overhearing one of the detectives at the next table order a spaghetti Bolognese followed by a T-bone steak with beans, peas, cauliflower and chips – and a bottle of Château Baron Philippe Rothschild 1961, no less!

He saw us staring at him, beamed, and explained that his job really took it out of him.

We stuck it for nearly two days. We went to the cinema on Saturday evening, but that made Annie even more furious. She’d wanted to see

La Cage aux Folles

but in the end we went to a James Bond film – I knew that none of the detectives liked foreign films, and it didn’t seem fair to drag them along to a French film with subtitles.

La Cage aux Folles

but in the end we went to a James Bond film – I knew that none of the detectives liked foreign films, and it didn’t seem fair to drag them along to a French film with subtitles.

Annie was black with rage because I’d put their choice first. When she put it like that, I saw what she meant. I hated the Bond film anyway – it was all about assassination attempts, and I couldn’t stand it.

The detectives were very fed up with us when we walked out halfway through it.

Finally, back in our hotel, lying in the bed, rigid with tension, unable to go to the loo without being observed, followed and overheard, we heard the following murmured conversation outside the bedroom door.

‘Are they going out again?’

‘No, they’ve turned in for the night.’

‘Is the target in there now?’

‘Yeah – target’s in bed with his wife.’

‘They don’t seem to be enjoying their holiday, do they?’

Other books

Wild Ride: A Bad Boy Romance by Roxeanne Rolling

London Folk Tales by Helen East

A Gun for Sale by Graham Greene

Swordpoint (2011) by Harris, John

Crucible of a Species by Terrence Zavecz

In Flames by Richard Hilary Weber

Blackbriar by William Sleator

Never Tied Down (The Never Duet #2) by Anie Michaels

Stalin's Children by Owen Matthews

Devil May Care (The Grizzly MC Book 12) by Jenika Snow