The Conquering Tide (84 page)

Read The Conquering Tide Online

Authors: Ian W. Toll

The verdict was received on the

Lexington

with disappointment and no small amount of out-and-out disgust. According to Truman Hedding, Mitscher was “very upset.” Hedding and Burke made a pact that they would forevermore commemorate the anniversary of June 19 by getting together and “crying in our beer.”

35

A

Yorktown

officer complained to his diary: “The Navy brass turned yellowâno fightâno guts. . . . Spruance branded every Navy man in TF-58 a coward tonight. I hope historians fry him in oil.”

36

Mitscher was immediately beset with proposals that he appeal the decision, that he point out in detail all of the advantages of going west and the potential hazards of remaining yoked to Saipan, but Mitscher refused all such entreaties and insisted on supporting the chief's decision. The operations officer of Task Force 58 was Jimmy Thach, the legendary fighter pilot who had developed air tactics to defeat the Zero with the slow-climbing F4F Wildcat. “I talked to Arleigh Burke very urgently to tell him that we would never catch those people if we didn't run toward them.”

37

The staff tinkered with various drafts of messages that Mitscher might send to Spruance in hopes of reversing the decision. According to Thach, he and Burke even

proposed that the task force commander threaten to resign his command. Mitscher seemed to take offense at the insubordinate chatter he heard on his bridge, and when Admiral John W. “Black Jack” Reeves of Task Group 58.3 radioed to urge going west, Mitscher slapped him down in uncommonly vehement terms: “Your suggestions are good but irritating. I have no intention of passing them higher up. They certainly know the situation better than we do. Our primary mission is to stay here to await W-Day [Guam landing] and assist the ground forces. . . . I hope in your message you are not recommending abandonment of our primary objective.”

38

Carl Moore predicted that the decision would provoke “a lot of kibitzing in Pearl Harbor and Washington about what we should have done, by people who don't know the circumstances and won't wait to find out.”

39

He was not wrong. The double guessing occurred in real time, as the CINCPAC staff in Pearl Harbor monitored dispatches and plotted the positions of the contending forces on a chart spread out on a table. John Towers, who wanted Spruance's job for himself, urged Nimitz to order Spruance west. Nimitz refused, according to a member of his staff, not because he disagreed with Towers's reasoning but because “it will be the beginning of my trying to run the tactical side of operations of the fleet from ashore.”

40

Spruance, characteristically, betrayed no signs of self-doubt. Having given his orders, he went to bed. But Mitscher and his staff, a quarter of a mile away aboard the

Lexington

, did not rest. They prepared their plans for the next day. Without need of the bombers, they would stow them in the hangars or fly them off to attack Guam and Rota. The flight decks would be kept clear for the fighters. “The die had been cast,” Burke said. “We knew we were going to have hell slugged out of us in the morning. We knew we couldn't reach them. We knew they could reach us.”

41

D

AWN ON

J

UNE 19 REVEALED ANOTHER FAIR DAY

, with a steady easterly breeze and mild seas. The clear blue sky overhead was not entirely welcome, as it offered no hope of concealment against the expected waves of Japanese warplanes. General quarters had sounded at 3:00 a.m., and the ships were buttoned up for actionâhatches dogged down, battle shutters secured over port holes, life vests and steel helmets served out to all crew.

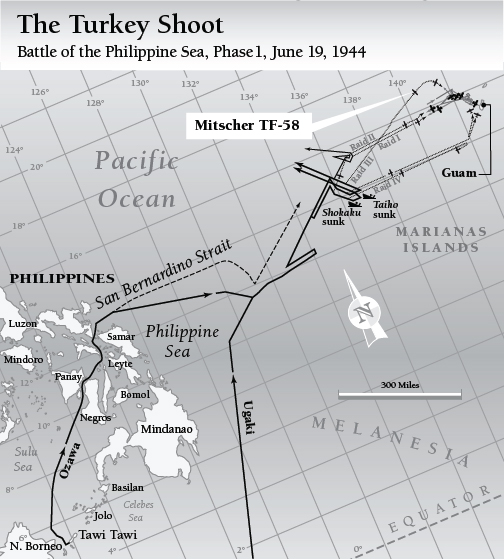

Task Force 58 was about 150 miles west-southwest of Saipan. Three task groups (commanded by Reeves, Montgomery, and Clark) were

arrayed in a line running north to south. Ching Lee's battleships and cruisers (Task Group 58.7) were positioned thirty-five miles west, in the direction of the enemy, to function as an antiaircraft screen. Harrill's Task Group 58.4, the weakest of the four task groups, was placed immediately north of Lee. Paul Backus, an officer on the

South Dakota

, recalled that the battleship's crew was thrilled to be placed in this advanced position, and sailors eagerly scanned the western horizon in hopes of spotting the Japanese fleet. The prospect of a naval gunfight prompted a “tremendous uplift in the morale of the ship. . . . [M]aybe the Japs were going to get a taste of five or six or seven new battleships all together for a change, and we would really go after their battle line. We even put our big colors up at the foretop.”

42

Search flights continued to come up negative. Radar-equipped planes from the

Enterprise

, launched at 2:00 a.m., had found nothing. A much larger air search departed at 5:30, covering nearly half the compass rose to a distance of 325 miles; still nothing. Longer-ranged Mariner seaplanes launched from waters off Saipan had found radar blips at 1:15 a.m., probably the van force under Admiral Kurita. The reported position placed the enemy ships about 330 miles away at a bearing of 258 degrees. But the report did not reach Spruance and Mitscher until 8:50 a.m., and the distance was beyond effective air-striking range.

With the first combat air patrol and antisubmarine patrols airborne, the task force turned west to gain sea room for the next round of flight operations. A few enemy “snoopers” intruded onto the southeastern fringes of the fleet, and were shot down or chased away. A lone Zero was taken down by antiaircraft fire. The combat air patrol fighters were ordered to climb to 25,000 feet.

At 7:30 a.m., radar operators noted a cluster of blips over nearby Guam. Hellcats from the

Belleau Wood

hurried over to Orote Airfield and tore into a group of Japanese planes. They were soon joined by reinforcements from the

Yorktown

,

Hornet

, and

Cabot

. In an hour-long air battle, about thirty Japanese planes went down in flames; only one F6F was lost. The morning massacre over Guam was followed by several more throughout the day, as planes launched from Ozawa's carriers sought refuge at Orote.

At 10:05 a.m., the

Alabama

's radar screens registered many bogeys about 125 miles west, altitude 24,000 feet or higher. This was the leading edge of Ozawa's first airstrike, arriving precisely when and where it was expected.

Arleigh Burke, on behalf of Mitscher, ordered all carriers to launch all Hellcats spotted on their decksâ“so we launched all our fighters, the whole blooming works.”

43

Fighter directors summoned the planes over Guam back to protect the task force with a two-word call: “Hey Rube!”

Throughout the task force, bombers and torpedo planes were launched and told to fly away to the east. For the moment they were superfluous, and if kept aboard they would only clog the decks, hangars, and elevators. The aircraft were to circle over the southern Marianas, well away from the incoming enemy planes, so that they would not clutter the radar screens or risk being misidentified.

In the rush to scramble, the Hellcat pilots did not bother to find an assigned plane. Each man simply slid into the first vacant cockpit and awaited the signal to launch in turn. Without pausing to rendezvous into group formations, the planes simply banked around their carriers and climbed into the west. Lieutenant Don McKinley of Fighting Squadron 25 (of the

Cowpens

) did not recall receiving any specific vector or altitude instructions. Knowing that the Japanese planes were coming from the west, he pointed his nose in that direction and hung on his propeller. Alex Vraciu took off from the

Lexington

and followed the instructions given by the fighter director officer (FDO) to climb at full power on vector 250. The steep ascent tested the limits of the F6F's Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engine, and some of the older and more hard-run planes fell behind. Vraciu's engine spat oil onto his windshield, obscuring his vision. His formation was a mess, and he could not make contact with his squadron because the radio circuits were congested with pilot chatter. (In written comments submitted after the battle, another squadron leader complained that “some squadrons still persist in âhogging the air' with instructions and idle chatter that should have been clarified and settled before their flight.”)

44

Peering through the oil-smeared windshield, Vraciu spied many enemy planes on an opposite heading, several thousand feet beneath him. Visibility conditions were almost freakishly goodâa rare atmospheric condition caused contrails to form at 20,000 feet or even lower. When the air melee was at its height, the sky was interwoven with a web of stark white lines. “We could see vapor trails of planes coming in with tiny black specks at the head,” said Ernest Snowden, head of the

Lexington

air group. “It was just like the sky writing we all used to see before the war.”

45

McKinley was climbing through 7,500 feet when he saw a three-plane

section of Nakajima “Jill” torpedo planes, painted brownish gray with the circular red

hinomaru

on their wings and fuselages, about 1,500 feet beneath him. He executed a wingover and slid in behind them. He fired a quick burst as the first plane swam into his sights. The plane entered a shallow dive, trailing smoke. McKinley chased a second Jill all the way down to sea level. Before he could overtake it and shoot it down, both planes reached the outer edge of Lee's battleship-cruiser task group, and antiaircraft bursts mottled the sky around them. McKinley fired a last burst and pulled away as the Japanese plane hit the sea and exploded.

This first wave of sixty-nine Japanese planes had been launched from the light carriers of Kurita's van force. About half a dozen were lost at sea during the long overwater flight. Others had drifted off to the south and made a run for friendly airfields on Guam. Those that remained on course for the American fleet were assailed by a swarm of Hellcats, and most went down in flames in the first minutes of combat. A handful of the intruders traded altitude for speed and made torpedo runs or diving attacks on Lee's battle line. One planted a 250-kilogram bomb on the

South Dakota

, doing little damage to the ship but killing or wounding fifty of her crew. Another crash-dived into the side of the

Indiana

, causing only trifling damage. The cruiser

Minneapolis

reported minor damage from a near miss.

The diarist and sailor James Fahey had witnessed plenty of naval action in the South Pacific, but he had never seen an air battle at close range. He was awed by the spectacle: “Jap planes were falling all around us and the sky was full of bursting shells, big puffs of smoke could be seen everywhere. . . . Bombs were falling very close to the ships, big sprays of water could be seen and Jap planes were splashing into the water.”

46

Lee's battle line had perfectly executed the role assigned to it by Spruance. It had provided an early warning radar “tripwire”; it had diverted and absorbed the brunt of aerial attacks; it had chewed up the enemy planes with antiaircraft fire. None of the first-wave attackers had reached striking range of the American carriers.

In the cramped and dimly lit Combat Information Centers (CICs), confidence surged. The combination of radar and fighter direction had come a long way since the relative dark ages of 1942. The morning's interception had been nearly flawless. On most carriers, the Combat Information Center was housed in a single large windowless compartment, one level below the flight deck amidships. The pilots' radio chatter was piped into the room through a loudspeaker. In one corner stood a vertical screen of transparent

Plexiglas. The ship's position was fixed at the center; a series of concentric rings measured distance in all directions. A bank of radar screens was positioned on one side of the screen. The fighter director officer and his assistants sat at a table on the opposite side, facing the screen. As the radar operators called out their readings, sailors armed with grease pencils marked up the screen with red and white “X's.” Red X's denoted bogeys, or planes not identified by IFF (“identification-friend-or-foe”) transmitters; white X's represented the American aircraft. With each radar sweep, the sailors wiped the screen clean with a wet cloth and drew new X's. As the minutes passed, the red markings marched steadily toward the center of the screen, and the white ones crept outward as they flew a course to intercept. The CIC personnel

watched the converging groups of red and white until the voices on the radio confirmed visual contact: “Tally Ho!”

During an air melee the radar screens provided little actionable data. Red and white X's were clustered together on the same corner of the screen. The radio circuits rang with confusing chatter. On June 19, however, the giddy tone of the voices on the radio left no doubt that the Americans were massacring their opponents. With each new sweep of the radar, there were fewer red markings. One or two red X's might continue toward the center of the screen, with the white ones following close behind. Each sequence ended with the screen wiped clean of all red X's, and a sailor made a small notation indicating the time and the number of enemy planes “splashed.” Sam Sommers of the

Cowpens

peeked into his ship's Combat Information Center on the afternoon of June 19 and noted a “foot-long smear of red at the end of lines of white âX's' coming from near the center of the panel.”

47