The Dictionary of Homophobia (124 page)

Numerous psychological studies and theories are interested in the causes of homosexuality and, for the moment, biological and genetic theories seem to be in vogue, in lieu of psychoanalytical and behaviorist formulations. These approaches clearly appear to be heterosexist, in that they only seem to be searching for a way to explain the deviance. What would seem to require explanation, is homosexuality itself and not sexuality in general, or heterosexuality in particular. However, homo-, bi-, or transsexual psychologists are attempting to change that perspective, becoming interested less in the causes per se than in the means of the development of personal identities. Other psychologists criticize the essentialist approach of the notion of sexual orientation by suggesting that our conventional categories, such as lesbians, gays, and bisexuals, are inadequate.

In North America, psychology is only now beginning to examine the evident heterosexist biases in clinical publications, research, and practices, as demonstrated by the American Psychological Association (“Division 44/Committee on Lesbian, Gay and Bi-sexual Concerns,” 2000; Herek, Kimmel, Amaro and Melton, 1991). The association also sided with gays, lesbians, and bisexuals in political and legislative fields (Committee on Gay and Lesbian Concerns, 1991). However, the lack of financial support and the remaining stigma attached to research on these questions has meant that heterosexism has not yet been completely eradicated from the field of psychology.

—Roy Gillis

Bayer, Ronald.

Homosexuality and American Psychiatry: The Politics of Diagnosis

. New York: Basic Books, 1981.

Bergler, Edmund.

Counterfeit Sex

. New York: Grune & Stratton, 1951.

Committee on Lesbian and Gay Concerns, American Psychological Association.

American Psychological Association Policy Statements on Lesbian and Gay Issues

. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1991.

Broido, Ellen M. “Constructing Identity: The Nature and Meaning of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identities.” In

Handbook of Counseling and Psychotherapy with Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Clients

. Edited by Ruperto M. Perez, Kurt A. Debord, and Kathleen J. Bieschke. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2000.

“Division 44/Committee on Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Concerns Joint Task Force on Guidelines for Psychotherapy with Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Clients. Guidelines for Psychotherapy with Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Clients,”

American Psychologist

55 (2000).

Duberman, Martin, and Ellen Herman.

Psychiatry, Psychology, and Homosexuality (Issues in Lesbian and Gay Life)

. New York: Chelsea House Publishing, 1995.

Ellis, Havelock.

Sexual inversion

(1897). New York: Arno Press, 1975.

Foucault, Michel.

Histoire de la sexualité

. Vol. 3. Paris: Gallimard, 1976–84. [Published in the US as

The History of Sexuality

. New York: Vintage Books, 1985.]

Freud, Sigmund. “Letter to an American Mother,”

American Journal of Psychiatry

(1951).

Haldeman, Douglas C. “Gay Rights, Patient Rights: The Implications of Sexual Orientation Conversion Therapy,”

Professional Psychology: Research and Practice

33 (2002).

Hamer, Dean H., and Peter Copeland.

The Science of Desire: The Search for the Gay Gene and the Biology of Behavior

. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994.

Herek, Gregory M. “Psychological Heterosexism and Anti-Gay Violence: The Social Psychology of Bigotry and Bashing.” In

Hate Crimes: Confronting Violence against Lesbians and Gay Men

. Edited by Gregory M. Herek and Kevin T. Berrill. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1992.

———. “The Psychology of Sexual Prejudice,”

Current Directions in Psychological Science

9 (2000).

———, Douglas C. Kimmel, Hortensia Amaro, and Gary B. Melton. “Avoiding Heterosexist Bias in Psychological Research,”

American Psychologist

46 (1991).

Hooker, Evelyn. “The Adjustment of the Overt Male Homosexual,”

Journal of Projective Techniques

21 (1957).

Hirschfeld, Magnus.

Transvestites: The Erotic Drive to Cross Dress

[1910]. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1991.

Kinsey, Alfred C., Walter B. Pomeroy, and Clyde E. Martin.

Sexual Behaviour in the Human Male

. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1948.

———and Paul H. Gebhard.

Sexual Behaviour in the Human Female

. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1953.

Krafft-Ebing, Richard von.

Psychopathia Sexualis: A Medico-Legal Study

. Oxford: F. A. Davis, 1898.

Leahey, Thomas H.

A History of Psychology: Main Currents in Psychological Thought

. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1997.

Socarides, Charles.

The Overt Homosexual

. New York: Grune & Stratton, 1968.

Weinberg, George.

Society and the Healthy Homosexual

. New York: St Martin’s Press, 1972.

—Abnormal; Anthropology; Biology; Essentialism/ Constructionism; Heterosexism; Hirschfeld, Magnus; Medicine; Philosophy; Psychiatry; Psychoanalysis; Sociology.

PUBLICITY

Publicity and advertising can be topical, fantastical, ideological, and even political, but most of all, they are economic objects. It is this essential characteristic that structures how publicity and advertising represents homosexuality, a fact that it doesn’t hide either. In October 2000, when questioned on the relationship between advertisers and homosexuality, Gilles Moreau, strategic planner for Publicis, responded: “I suppose that in France, [advertisers work from] an old base of mistrust, overcautiousness even. We don’t want to offend certain customers, nor do we want a message to be detrimental to the trademark.” In this, he euphemistically expressed the marketing “worries” that exist in the constructs of advertising which, in their unwillingness to “offend” the public, are potentially homophobic. This position, however, cannot begin to describe the enormous variety of positions taken by advertisers in media; although it is apparent that in targeting a particular market (i.e. in order to seduce the greatest number of consumers), the representation of homosexuals in publicity and advertising follows the social evolution (or lack thereof) of the image of homosexuality. In this way, advertisers adopt the prevailing ideology that is, depending on the times, if not homophobic, then at least

heterosexist

. In this sense, we can distinguish three significant periods in the representation of homosexuality in publicity and advertising. From the very first advertisements through to the end of the 1950s, homosexuality was either ignored or hidden; from the 60s to the early 90s, it was caricatured. Since then, however, homosexuality has been reified. Hidden, caricatured, and reified: so many forms assumed by an oft-present homophobia that never speaks its name.

Hidden

From advertising’s early days until the end of the 1950s, homosexuality did not exist, at least explicitly. A social taboo, it was unthinkable in advertising, which focused on representations that were deemed “acceptable” by the “greatest number.” The concept of marketing itself, which originated in the United States in the 50s, dictates this same law of the masses. In order to construct efficient advertising messages, marketing draws from the patriarchal culture of Western countries that place the nuclear

family

at the core of their values, and in which there is no room for homosexuality. Thus, under the aegis of marketing, we can see in the messages that advertising offers a social world that, while not an exact photocopy, is a construction of the values that exist in Western societies, as well as the taboos that shape them. Thanks to the magic of language (whether verbal or otherwise), there is no communication that is transparent; even, and perhaps especially, to the one who expresses it. If showing “values” is the intended goal, and if they are consequently more or less explicit, then taboos show through just as well—not at the explicit level of the message’s meaning, but at the implicit level where the semiotics of diverse connotations occur. Thus, homosexuality is unconsciously present in the advertisements of this period, like a sort of Freudian slip of reality that does not yield to its own denial.

Thus we see, as early as 1916, the company Procter & Gamble—emblematic of traditional American culture—produced an advertisement for its product Ivory Soap that appeared in

National Geographic

: a perplexing representation of athletes after a game who are looking at one another while washing. The caption is also rather ambiguous: “Not the least of the pleasures of a hard game is the bath that follows it. For it is just after the final whistle when you realize for the first time how warm you are and how your skin is chafing, that the cooling, soothing, refreshing qualities of Ivory Soap are most appreciated.” The scene takes place in the locker room, a place of many homoerotic fantasies. There is also a man who is bending over with his back to the others, as if he were picking up his soap; the slogan says it all: “Ivory soap … it floats.” Beneath the superficial promotion of heterosexual virility (i.e. the athlete), there are a number of signposts that lead us to see a highly sexualized representation of relations between men. It is once again in the locker room, but not in the showers, that underwear-maker Arrow chose to depict its models. In its 1933 campaign to promote a line of underwear’s new array of colors, the ad’s slogan is rather surprising: “And now, the Shorts with the Seamless Crotch Go Gay! (But Not Too Gay).” The caption, and notably the use of parentheses, can be interpreted at different levels. The ad’s text (aimed at the department store purchasing managers) further explains that the colors are “not too outlandish” (“Gypsy’s Delight” or “Tropical Sun”), but are instead “he-man.” But while the word “gay” was used by homosexuals to refer to themselves as early as the 1920s, it is uncertain whether the word as used in the Arrow ad was meant to suggest a homosexual component, whether consciously or not.

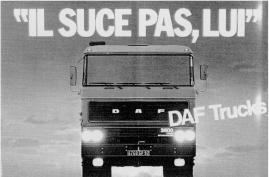

A 1978 French ad for DAF Trucks. Its message,

“Il suce pas, lui”

(It doesn’t suck) has a double meaning: this truck does not consume a lot of fuel, but also it is not a vehicle for “fags,” but rather real men….

These two examples are characteristic of this paradox between the spoken and unspoken, which is revealing of the status of homosexuality in the societies that produce these messages. It will not be long before the homophobia present in this paradox expresses itself explicitly: from the 60s to the 90s, advertising and publicity become openly and, it could be said, nonchalantly homophobic.

Caricature

With the 1960s and the mass popularity of television, the nature of advertising and publicity changes: advertising enters the era of the narrative, whose different genres it will exploit. From this point of view, the figure of the homosexual is systematically set in the medium of the comical, from satire to burlesque. This period marks advertising and publicity’s most overtly homophobic years, during which we see the frequent appearance of caricatured figures such as the “queen” and the “transvestite.” These humiliating clichés are regularly used to describe and stigmatize homosexuality as a “monstrosity” (in the etymological sense) which the public is supposed to look upon with both amusement and consternation. The face of the trans-gender becomes a sort of metonym for homosexuality. A good example is a television commercial for Hamlet cigars from 1987. In a horror film setting, the camera explores the sheet-covered body of a Frankenstein-like creature, which suddenly sits upright and looks timidly under its sheet. What it discovers visibly troubles it: we see it swallow nervously and we hear sad music in the background. Then the creature reaches for a cigar, no doubt to console itself over its terrible discovery; it crosses its legs and we discover that it is wearing stockings and high heels. Under the guise of

humor

, then, the transgender is explicitly (and literally) depicted as a monstrosity.

When the homosexual is not playing the role of the funny, sympathetic clown, he intervenes in narratives constructed around the motive of

trompe-l’oeil

and the “mistake,” from which the discovery of the “monster’s” true “nature” provokes various levels of panic. For example, in a Bouygues Telecom campaign for its prepaid telephone card that offers “no long-term commitment” depicts a man who discovers that his young bride is, in reality, a young groom. Homosexuality is thus cast down to the domain of the

abnormal

or pathological.

It is precisely this “abnormality” that interests advertising agencies seeking originality, in the hopes of distinguishing themselves from the masses. It is a strategic choice of representation, and not simply a matter of unfortunate and unintentional consequences. A common response from advertising agencies when confronted on their homophobic tendencies is to describe it as an inevitable consequence of the brevity of the medium, which must say a lot in very little time and with few words and images. Arguing the necessity of having to use analogy and metaphor, which “represent more quickly and better,” advertising agencies attempt to depoliticize a construction that is nonetheless eminently ideological. However, there is a phenomenon that has recently arrived to counter such an argument: the emergence of gay and lesbian-targeted marketing, in response to the evolution of the gay and lesbian community in Western nations that is not only political, but affluent. In this regard, advertisements that specifically target gays and lesbians are rarely in the realm of the burlesque and instead present less “metaphorical” representations of homosexuality: they are, therefore, possible. A significant example is a 1997 Johnnie Walker Red campaign using gay men. A print advertisement shows a “bunch of buddies” who are multicultural, and whose physical appearance does not allow us to distinguish them from other men their age. The politically charged slogan states, “For the last time, it’s not a lifestyle, it’s life.” The advertisement thus criticizes the traditional message popularized by advertisers that homosexuality is a “lifestyle” choice. In this, we have the beginnings of a discourse that chooses to oppose the usual discourses on homosexuality.