The Dictionary of Homophobia (144 page)

The other tradition is the Jewish tradition. In the Hebrew Bible, when Abraham was very old and his wife Sarah was infertile, Yahweh promised him uncountable progeny, “as numerous as grains of sand and stars in the sky.” Thus the “promise to Abraham” became a leitmotif throughout the Bible. Sarah became pregnant, and indeed presented him with a progeny. The Jewish people were slowly establishing themselves. And it is Abraham’s nephew, Lot, who arrived at

Sodom and Gomorrah

. These two

perverse

and

sinful

cities were destroyed by divine punishment: fire and brimstone. In Judaism, fire is both a symbol of purification and sterility. But that is not all: when Lot’s wife turned around to look at the disaster in spite of the divine ban, she was transformed into a pillar of salt; as a result, salt is also a symbol of sterility. We can see that the mythical coherence that associates sodomy, sexual abnormality, divine punishment, and symbolic sterility is deeply rooted in the past.

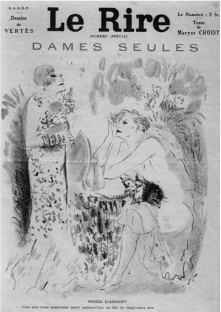

Cover of the satirical magazine

Le Rire

(1932), devoted to the

dames seules

(single women). “Silver Anniversary—And to say that we could have a son of twenty-five today.”

It is in the Middle Ages that both traditions merge, notably through Thomas Aquinas, the Italian Catholic priest who is regarded by the church as the ideal teacher for those studying for the priesthood. But in those days, sterility was a notion whose axiological valence remains very ambiguous. Certainly, infertility remains associated with everything negative, a curse from God; but at the same time, the refusal to procreate can be interpreted as some kind of asceticism, or purity, as demonstrated by the rules of celibacy, abstinence, and chastity the clergy imposes on itself. Incidentally, the Knights Templar and other heretics of the Middle Ages, such as the Cathars, considered this purity, and this refusal to reproduce, so important that they were accused of favoring relations between men. From then on, if infertility is a curse, the refusal of fertilization is nevertheless of potential value, although always suspected of a complacency that is

against nature

.

Under the Ancien Régime, this ambiguity of the notion of sterility continues. In the thinking attributed to the libertine, sodomy remains unnatural, certainly, but it is often introduced as an advantage, notably for women, because it does not result in any inconvenient pregnancy that would reveal infidelities and subsequently immobilize the would-be mother for the duration of her term. As Mirabeau said, “

debauchery

does not produce children.” Pleasure between men or between women seems all the more free and attractive as it appears to be free from the constraints of reproduction. However, the idea of sexually ecstatic freedom is at the same time frightening and, in Christian rhetoric, the sterility of sodomitic relations often appears as the paradoxical opposite of an excessive prodigality or a wasteful spending of bodily fluids. Nineteenth-century French slang even gave gays the feminine label of

gâcheuses

(wasteful ones).

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the notion underwent a series of mutations and was increasingly associated with the theory of

degeneration

and the diverse by-products of medical and scientific rhetoric. It is during this period that the idea spread that masturbation and

inversion

made an individual sterile: it was no longer the practice that was “sterile,” but the person in general who became sterile. It is when the homosexual becomes a separate character in the medical and psychiatric discourse that sterility is no longer part of the practice, but becomes an integral part of the topic, thus defining its real “essence.” Homosexuality is no longer part of a question of sin, but rather pathology: the “abnormality of the inverted” is related to a “nervous degeneration” that results in biological sterility. And even if the individual is not himself sterile (doctors are well obliged to recognize that he is not sterile, because homosexuals in those days were frequently married and had children), his children will be. And if his children are not sterile, the “scientific” curse will befall his grandchildren. This idea can still be found today in certain arguments stemming directly from the nineteenth century, such as that by psychoanalyst Jean-Pierre Winter, who described the supposed “symbolic wound” suffered by the child raised by same-sex parents in terms that would be laughable had they not been given serious consideration by a newspaper such as

Le Monde des débats

(March 2000): “It is likely that it is translated in the first, second, or even in the third generation, by a halt in the transmission of life: by madness, death, or sterility.” The theory of degeneration thus adds the dimension of a morbid heredity to the agenda. In this perspective, the homosexual often appears as a sterile runt, someone who represents the “end of the race,” the last stage of a sterility accumulated over the course of generations.

Thus, the rhetoric of the period propagated the fantasy of a collective sterility that could spread and destroy an entire state; this fear spread in a context that was increasingly marked by the expansion of nationalist movements in Europe. More than ever, a nation’s power was defined by the number of its inhabitants and available soldiers: the management of populations evoked by Michel Foucault, which he called “biopower.” The womb was thus the object of an official politic that required that women be reduced to their reproductive function; in the same way, the fear of a decrease in the birth rate, especially after World War I, justified the persecution of homosexuals: once again, sexism and homophobia were hand in hand. This paranoia, which was propagated all over Europe, peaked in Nazi

Germany

and Communist Soviet Union, regimes whose policies of the instrumentalization of the body made homosexuals sterile objects “by nature,” useless to the state and dangerous to society: it was thus necessary to cure them—or get rid of them.

This vision of gay sterility as a threat to the state’s power remains widely present in today’s consciousness. In 1998, during a conference for the Concerned Women for America, Wilma Leftwich evoked the existence of a world plot “to reduce the American population thanks to the availability of abortion, the sterilization of mothers with many children, and the promotion of homosexuality.” Moreover, beyond national concerns, homosexuality threatens humanity’s very survival, which is often expressed as the ultimatum of the homophobic argument: “Yes, but if everybody was gay, there would be no one left,” as if the human race would disappear from the face of the Earth if

discrimination

and homophobic persecution were to cease; an apocalyptic fantasy all the more absurd when those who propagate it are afraid of global overpopulation. Nevertheless, this argument remains common in various discourses; French novelist Marguerite

Duras

, for example, was not afraid to warn against the universal advent of homosexuality in 1987’s

La Vie matérielle

(published in English as

Practicalities

): “It will be the greatest disaster of all times. Slowly at first. We’ll observe a slight depopulation.… It is possible that we witness the final depopulation together. We would sleep all the time. The death of the last man would go unnoticed.”

However, it is necessary to insist on the extremely particular character of this association between homosexuality and sterility. Indeed, even today, in numerous cultures in the Arab world, Africa, and Asia, homosexual practices are not at all incompatible with (heterosexual)

marriage

and procreation. In addition, in certain ethnic minorities of the Western world, within which the collective progeny has a greater fundamental value than the simple institution of marriage, many men try hard to conceive children before making a commitment to gay life. In fact, in these sectors of society, at least for men, the commandment of the “procreative order” would be as follows: “Whatever your sexuality is, if you have children, race is perennial and honor is upheld.” While, in the Western framework, the simple fact of reminding people that homosexuals are not sterile often constitutes an incredible paradox, in several other societies, sterility does not constitute irrefutable symbolic evidence that could be used to oppose gay relations.

From Mythical Sterility to Forced Sterilization

The homophobic myth of sterility is inseparable from the paradox of “reproduction of the sterile.” Guy Hocquenghem reminds us that “the transmission of homosexuality [retains] this slightly mysterious character of the advancements of desirous production; in

Lundis en prison

[Mondays in prison], Gustave Macé quoted a chief of police who defined gays as ‘These people who, while not procreating, tend to multiply.’” Thus, the very idea of the sterility of gay relations must be deconstructed, even if it is necessary to untangle ourselves from the categories of social thinking, which in truth requires a certain effort. In reality, the notion of sterility only makes sense with regard to a reproductive end, which it fails to achieve. No one would think that kissing is a sterile practice, although, objectively, kissing does not produce a child; but since procreation is not the aim of a kiss, it is never thought as such. In addition, there is no reason for considering that other sexual practices (e.g., fellatio, cunnilingus, sodomy, or even simple caresses) are sterile, except if you believe that the ultimate goal of any sexuality has to be procreation, which indeed is often the presupposition of traditional morality. From then on, as far as individuals do not expect pregnancy to result from kissing or from sodomy, it is technically inaccurate to speak of the sterility of these practices. Although it allegedly provides a form of social evidence that is difficult to shake, this idea of homosexual sterility is related to a historically dated device, the obstinacy of which betrays a lack of conceptual elaboration in the rhetoric of those who take advantage of it.

Under these conditions, the idea of “sterility” finally turns out to be neither true nor false, but simply

performative:

: it tends to produce its own foundations by trying to impose itself upon social or biological reality, sometimes in a truly criminal logic. The reasoning is simple: gays are “sterile,” and if they are not, they must be sterilized. Gays “cannot” have children, and if they have any, they must be taken away.

Conservative French politician Pierre Lellouche was undoubtedly aware of what he said when, from his seat in the National Assembly during the debates on PaCS, he shouted, “Sterilize them!”—which, sadly, became famous. Actually, since the beginning of the twentieth century concurrent with the first developments in

genetics

, medicine has often tried “to cure” homosexuals or, in the case of “failure,” to sterilize them. A collective, forced sterilization was recommended as early as 1904 by Austrian psychiatrist Ernst Rudin, who, in 1933, joined a committee of experts on heredity overseen by Heinrich

Himmler

. As a result, the Nazis implemented this measure, but it was not carried out in a massive way because Himmler still “hoped to cure them.”

More recently, the debates in

France

on the recognition of same-sex couples and their right to

adoption

created the perverse logic of a similar device, although obviously less violent. Indeed, until then, gays had often been accused of refusing to assume the “responsibilities” of family and parental “functions.” Now, when gay couples wished to adopt, they were told that they had to get over their desire for a child. Currently, French law permits only the adoption of a same-sex partner’s existing children; in effect, the symbolic sterility of homosexuals justifies, in return, the “social sterilization” carried out by the law.

The question of access to medically assisted conception that arose in the 1990s also brought to light a performative logic by which the supposed sterility of homosexuals is invoked as a pretense to refuse them the right to fertility. Therefore, the “bioethics” laws limited medically assisted conception only to single women and heterosexual couples. The paralogical functioning is always the same: such techniques aim to “repair” nature by giving sterile heterosexual couples an “artificial” access to reproduction. This capacity to be able to “repair nature” could give way to an awareness that this “nature” does not impose itself upon human choices, and that there is nothing that should prevent alternative conception techniques from being available to all. The tendency, however, has usually been carried out in the opposite direction: instead of accepting the idea that there is no transcendence of “nature,” the powers-that-be choose to “mimic” nature instead, in an effort “to keep up appearances.” It is this understanding of nature (denied

in practice

by the movement that purports to “repair” it) which is, in a strangely paradoxical gesture, opposite to the demands of gays and lesbians. Here, as elsewhere, free humanity alienates itself (and oppresses its homosexual members) by subjecting itself to the idols which it created.

French legal scholar Daniel Borrillo showed how the heterosexist argument linking heterosexual coitus to the survival of humanity has become increasingly ridiculous, considering modern reproduction techniques which, by means of a circular reasoning, are denied to gays and lesbians. However, ideas that perceive homosexuality as “pure desire” in comparison to heterosexuality (which is inevitably reproductive) do not lack for contradictions. Indeed, we do not force heterosexual bachelors to get married, or the bridegrooms to father children (or adopt them if they are biologically sterile). To define sexuality according to its reproductive value would, finally, mean forbidding contraceptive pills and abortion, which explains why the groups most violently opposed to contraception and the voluntary termination of pregnancy are also generally the most violently homophobic. As Borrillo says, not without humor: “One must wonder if the reproduction argument does not hide a certain anti-gay hostility.” In the end, if, as Boutin said, homosexuality is a “sterile and short-lived project,” this “sterility” can first be found in the mind of homophobes. This is exactly why it is dangerous for gays and lesbians.

—Sébastien Chauvin and Louis-Georges Tin