The Dictionary of Homophobia (134 page)

He was immediately brought to the hospital, but his condition was too fragile for doctors to attempt to operate. Shepard fell into a coma, and as he lay dying, a candlelight vigil was held by the people of Laramie. Matthew Shepard passed away on Monday, October 12, 1998, at 12:53 a.m.

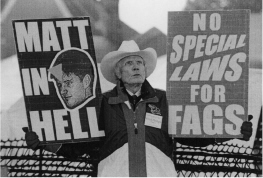

Reverend Fred Phelps, Minister of the Westboro Baptist Church Community, protesting during the funeral of Matthew Shepard.

Shepard’s murder immediately mobilized gay and lesbian organizations into action. Three days after his death, another candlelight vigil was held on the stairs of the Capitol in Washington, DC; among those in attendance were Senator Ted Kennedy, Congressman Barney Frank, and actress Ellen DeGeneres, who only months earlier had come out publicly on her television series

Ellen

. The Human Rights Campaign, the largest LGBT lobby in the United States, launched a campaign inviting gays and lesbians around the world to dress in black in memory of Shepard. A private funeral took place on October 16 in Casper, Wyoming. However, anti-gay demonstrators attempted to disrupt the ceremony with cruel, hate-filled signs, such as “Matt in hell.” Having organized more than a few demonstrations of this kind in the past, Reverend Fred Phelps of the fundamentalist Westboro Baptist Church subsequently unleashed heinous, hate-mongering rants against homosexuals including Shepard both on his website

godhatesfags.com

and in the

media

. Indeed, Phelps even petitioned the city of Casper in 2003 for a permit to build a monument praising Matthew’s death as divine vindication.

On both sides of the issue, the mobilization continued. Vigils took place across the country as the murder became a national issue, emblematic of systemic homophobia in America. Both of Shepard’s killers, Russel A. Henderson, twenty-one, and Aaron J. McKinney, twenty-two, were soon arrested. At their trial, the defense’s strategy consisted of denying the homophobic character of the murder; it was claimed to be simply a robbery turned bad. Moreover, explained McKinney, “I do not hate gays; I even have a gay friend.” Further, he also contended that he was completely unaware that Shepard was gay. That said, this theory completely contradicted both of the accused’s first statements, their girlfriends’ testimonies, and a letter written by McKinney himself, discovered afterward, in which he admitted: “Being a verry [sic] drunk homofobick [sic], I flipped out and began to pistol whip the fag with my gun.” The defense subsequently tried a second tactic: the gay panic defense, which implicitly acknowledged the homophobic character of the murder. Frequently used in trials of this kind, this strategy allows the criminal to appear as the victim of the victim: McKinney indeed asserted that Shepard had made indecent advances, which, in a twisted sense of logic, would have “justified” his homophobic panic and, hence, murder. However, this brazen attempt to rationalize homophobic violence was overruled by the judge. In the end, both men were convicted and sentenced to two consecutive life terms in prison; they escaped the death penalty thanks to the intervention of Matthew’s parents, Denis and Judy Shepard.

Since then, Matthew Shepard’s murder has profoundly marked the American consciousness. Over thirty music artists have composed

songs

in his memory, including Melissa Etheridge, Tori Amos, and Elton John, and numerous plays, films, and works of literature have been produced. However, beyond the facts of the case, why did this particular tragedy resonate so deeply with the American public, both gay and straight? Indeed, there has never been a lack of homophobic murders every year, and until Shepard’s, none had managed to gain the interest of the American people; not even Brandon Teena, the transgender who was raped and murdered and whose tragic story was depicted in the award-winning 1999 film

Boys Don’t Cry

.

In the case of Matthew Shepard, several reasons can be identified. First of all, the circumstances of the crime had the feel of a full-scale American tragedy: a good-looking, nice young man set upon by two hateful criminals; the audacity of their attack; and the tragic martyr symbol of Shepard himself, bound and tortured, found in the middle of nowhere. But it was more than that; there was also his family. In past cases when gays or lesbians were murdered, it was not uncommon for their families to want to suppress the case to avoid disclosure of the deceased victim’s sexuality. In Shepard’s case, however, his parents wanted to make a lasting commitment to their son; they spoke out at rallies and to the media, and soon thereafter created the Matthew Shepard Foundation to fight against hate crimes, in memory of their son so his murder would not be in vain. The foundation’s stated goal is “To replace hate with understanding, compassion and acceptance.” Matthew’s death also instigated the coordination of gay and lesbian networks, notably around the Human Rights Campaign, which played an instrumental role in helping to tell his story around the world. His murder crystallized the issue of homophobia for millions, making it personal and thus “real”; a revelatory moment which opened people’s eyes to the reality of homophobic violence in the United States.

“But remember one thing,” said Walter, a friend of Shepard’s. “No matter what good comes out of this, the price paid will be too high.”

The Matthew Shepard Act, a federal bill that proposes to amend the 1969 hate crime law to include crimes motivated by the victim’s sexual orientation, currently awaits passage. Although the bill was approved by the United States Senate in September 2007, it is expected to be vetoed by President George W. Bush.

—Louis-Georges Tin

Berrill, Kevin, and Gregory Herek, eds.

Hate Crimes: Confronting Violence Against Lesbians and Gay Men

. London: Sage Publications, 1992.

Gibson, Scott, ed.

Blood and Tears: Poems for Matthew Shepard

. New York: Painted Leaf Press, 1999.

Human Rights Campaign.

http://www.hrc.org

(accessed April 24, 2008).

Kaufman, Moises.

The Laramie Project: A Play

. New York: Vintage, 2001.

Loffreda, Beth.

Losing Matt Shepard: Life and Politics in the Aftermath of an Antigay Murder

. New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 2000.

Mama, Robin, Mary Swigonski, and Kelly Ward, eds.

From Hate Crimes to Human Rights: A Tribute to Matthew Shepard

. Haworth Press, 2001.

—North America; Protestantism; Violence.

SIN.

See

Against Nature; Bible; Debauchery; Theology; Vice

SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIONISM.

See

Sociology

SOCIAL ORDER.

See

Symbolic Order

SOCIOLOGY

The very existence of the category of “homosexuality” is so well associated with the psycho-medical field that, at first glance, sociology would have no apparent link to the phenomenon of homophobia. In fact, for over a century, sociology’s most common response to homosexuality has been silence. But this silence is not without significance: it is thus necessary to understand sociology “beyond sex.” The last part of the twentieth century is the start of a new era; sexuality will break into the field of sociology under the simultaneous influences of internal evolutions and external events.

Sociology “Beyond Sex?”

Those who worked in the field that would eventually become sociology had no particular doctrine with regard to homosexuality, but rather opinions that had no direct relation to their theoretical work. Some expressed hatred (or disgust), or a form of tolerant comprehension, but, for the majority, we have no clue what their opinions were on the subject. The few elements that can be gleaned here or there stem only from chance or anecdote and for one simple reason: sociologically speaking, sexuality was not constituted as an object.

Rousseau, for one, made his disgust quite apparent, but this was based on his personal experience of having been the subject of three attempted seductions. The Moor who took care of him during his stay in Turin and who, after his initial caresses, expressed his desire to “go on to the most filthy liberties,” had an impact on Rousseau that was so frightening that “the most hideous hag” was, in his eyes, transformed into an object of adoration by the memory of this encounter.

In a text that Gilles Deleuze qualified as “difficult and beautiful,” Marx enigmatically noted the necessity of thinking of sexuality as a “relation between human sex and non-human sex,” which opened the possibility of a non-heterosexist understanding of sexuality. But in

The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State

(1884), Frederick Engels let loose a torrent of hate against what he called “filthy

vices against nature

” by writing: “The debasement of women has had its revenge against men and has debased them to the point of making them fall into the repugnant practice of pederasty and to dishonor themselves by dishonoring their gods through the myth of Ganymede.”

Expressed or not, this sharing of common prejudices would prove to be long lasting, and not only in Europe: in 1927, in a famous monograph in which he described the life of hobos, those itinerant and marginal workers of the great construction sites in turn-of-the-century America, Niels Anderson made moral judgments on the relatively common behavior of the group, notably the relations between men; moral judgments that did not seem to upset anyone. This type of “evidence” of ordinary homophobia was such that it even imposed itself on those who were in a position to analyze and fight it: it is difficult not to interpret the silence of the “invisible” homosexual Norbert Elias, a great theoretician of the process of the “civilization of morals,” as the effect of powerful self-censorship. It is necessary to read between the lines in order to guess that he was quite conscious of the possibility of studying the field of multiple sexualities and their link to affection as a legitimate object, whose existence he briefly and discreetly suggested from time to time.

This absence of specific theorization is not in the least mysterious: sexuality was constructed as a scientific object in the fields of medicine and psychiatry, and it was in these same discourses that the term of homosexuality appeared. When Michel Foucault retraced the genealogy of a

scientia sexualis

contrasted with an

ars erotica,

in which he demonstrated the mechanisms of a new category, that of “perverts,” he was not working in the realm of social science, but rather what would become the “humanities.” And if we need to search for the emergence of counter-discourse, it may be found in

literature

: since the Romantic movement and throughout the entire twentieth century, there was a growing body of literature that was resistant to the dominant homophobia.

For all that, sociology was not absent from the scene: it was present in two methods that were both different yet invisible. The first was in the omnipresent form of “naïvely”

heteronormative

analyses, and the second was in the literary works that present fictional universes and characters, to which anti-homophobic sociological studies of the late twentieth century will confer a conceptual status.

To speak of heteronormativity is to name something obvious that runs through the sociological tradition in its entirety: sexuality is reduced to its institutional forms; in other words, to the

family

. In this, French sociologist Emile Durkheim was exemplary. In 1892, on the subject of the conjugal family, which in his eyes represented the most complete family structure, he wrote: “Marriage is the foundation of the family and at the same time is derived from it. Thus, all sexual union that is not contracted in the matrimonial form is a perturbance of duty and the domestic bond, and, since the day that the State itself first intervened in family life, a disruption of public order.” He further qualified the non-married couple as “immoral.” In his other texts, notably

Le Suicide,

Durkheim analyzed celibacy as being dissolute, a chronic instability that disrupts the well-being of society, which requires the necessary integration of the individual among permanent and instituted groups.

Thus, Durkheim presented his argument. It is nonetheless interesting to question the conditions of a possible ordinary homophobia, that is to say “naïve” (there is no indication that Durkheim gave any thought to homosexuality). The reason is seemingly simple: sexual “

perversions

” belonging to the sphere of psychopathology—of individual psychology—were of no concern to “social facts” and did not enter into the field of sociology. A social pathology did exist, as an object of criminology, but it concerned crimes, not perversions. At the same time, there was a more profound motive than merely the divisions between clinical disciplines. Until very recently, one’s

private

life, including sexual practices, was considered to be completely separate from public life. It was Herbert Marcuse, then Foucault, to whom we owe the establishment of an intrinsic link between power and sexuality. In this regard, Durkheim was neither worse nor better than other sociologists: the state’s role in the institutionalization of “normal sexuality” seemed to him eminently positive for society’s good functioning. Heteronormativity was simply the expression of a common view and expression. The heterosexist order was so evident, so visible, that it became totally invisible, even to the most enlightened minds.