The Dictionary of Homophobia (135 page)

Sociology in the Arena

Of the three sources from which anti-homophobic studies obtained their points of reference, the first was in the production of a sociology of deviance. In particular, it was the work of American sociologists who espoused a theoretical current that could be called “interactionist.” Their powerful critique of the “normal vision” of the “abnormal” can be summarized in three points:

1. All transgressions of dominant standards are produced and constructed. No conduct, as strange or minor as it may be, is deviant unless it is designated as such. It is social

labeling

that makes it deviant. This complex operation results in a process of continuous collective interactions, in which the currents of opinion, the

media

—the “constructors of morality”—play a decisive role.

2. There exists, therefore, in varied forms, a general mechanism that produces “deviants”: the symbolic humiliation, the constitution of certain groups or individuals into lesser members of society; thus it is legitimate that they be of little consideration, or even persecuted. This mechanism is

stigmatization,

or negative identification.

3. The effects of these mechanisms on their targets include self-loathing (“disidentification”); feelings of

shame

, isolation, and contempt for one’s peers; grouping (“differential association”); collective struggles for rehabilitation (transforming the “stigma” into an “emblem”); and denunciation of repressive and discriminatory policies.

These studies (by Howard Becker and Erving Goffman, notably) did not directly deal with homosexuality (even if, in passing, homosexuals were included as one of many examples used to illustrate a particular analysis), but they gave rise to new ones, and their contribution was fundamental. They supplied a new theoretical framework where every deviance was denaturalized and susceptible to being considered from the point of view of an historical process, by which that which has been created can be undone. Homosexuals were de-characterized: they belonged to the vast category of those who, at any given time, found themselves among those who transgressed the norms; homophobia was linked to this grand gesture of social “labeling,” subject to being analyzed and transformed. Homosexuals opened a breach in traditional sociological culture by enlarging the notion of deviance, equated until then with minor disruptions, such as juvenile delinquency, to include conduct that was “pointed out” and discriminated against. Larger still, homosexuals constrained sociologists to deal with the problem of the arbitrariness of standards by the virtue of their multiplicity, construction, and their ability to change.

It was from this theoretical arsenal that the first strictly sociological studies dedicated to gay lifestyles were conducted in the mid-1970s, including the mechanisms of deprecation and homophobic discrimination, and the individual or collective strategies of those responding to their own stigmatization. While sociology is transformed through itself and through the debates that are internal to the history of the discipline, its transformations are also obviously linked to social changes themselves and, as an adjunct to this, to activist movements.

The political developments linked to the experience of minorities in the United States, the appearance of strong and organized gay and feminist movements—in short, the explosion of militant protests in the political field—constituted the second source of inspiration for a sociological literature oriented against

heterosexism

. The growing interest in gay and lesbian studies in the US has no equivalent in

France

. It must be noted that gay and lesbian studies developed in an interdisciplinary way, at the crossroads of philosophy, history, and literature, while sociology remained largely foreign or resistant to this larger intellectual movement, in which sociologists still participate rather marginally.

The great issue for those working in gay and lesbian studies is “the politics of identity” and what we could call the “identity dilemma.” Doesn’t the fight against all forms of homophobia run the risk of confining homosexuals in the trap set by a heteronormative social order? Of imprisoning them in a homogenous category in which a person’s complete identity is defined by his or her tastes, dispositions, and sexual practices? It is a dilemma that was brutally distilled by David Halperin, for whom the gay and lesbian identity is “both politically necessary and politically catastrophic,” because it is “both a homophobic identity as it is totalizing and normalizing, and an identity of which all negation and all refusal are no less homophobic.” The contemporary queer movement, dominated by the theoretical work of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, searches for a radical exit from this dilemma by deconstructing the very notion of gender, by tracing a path that is both non-separatist and non-assimilationist, and by “non-defining” the sexual (at the risk of dissolving it) as “the open matrix of possibilities, divergences, convergences, dissonances, resonances, weaknesses, or excesses of meaning when the constitutive elements of someone’s gender and sexuality are not constrained (or cannot be) to monolithic significations.” Further, it would be necessary to acknowledge Foucault, who is not a sociologist, obviously, but whose work strongly inspires these debates.

However, be it a question of the sociology of deviance or of gay and lesbian studies

,

one thing is striking: the realities examined by these approaches—including the problems they uncover, and the concepts they construct—all existed previously in literary creation, as demonstrated by Didier Eribon’s study on a “minority morality” based on Jean Genet’s works. It is the reason that allows one to speak of a “virtual sociology” with regard to the long period when sociology was either mute on the subject of homosexuality or passively collaborated with the ascendancy of a heteronormative power. Sociologists are in the habit of looking for their problems and their data in social “reality.” They often forget that art (including literature) constitutes an inexhaustible and often premonitory reservoir of representations and theories which they would do well to seize: the fictions of artists anticipate and propose realities that may appear to have little legitimacy, or even seem outlandish, but that nonetheless constitute powerful devices of discursive resistance.

Regardless, gay and lesbian activism in France crystallized itself around two major events whose consequences for research have proven to be productive. Firstly, gay activism linked to

AIDS

; specifically, the idea that homosexuals were, first and foremost, individuals, albeit contaminated: not only did this help to shed homophobic stereotypes and reveal that homosexuals were as worthy and respectable as anyone else, but it also gave rise to institutionally supported research. There is no doubt that this research contributed to a better understanding of gay and lesbian experience as legitimate and not as the corrupt behavior of a few unhinged individuals.

The long battles that finally ended in the tumultuous adoption of the

PaCS

civil-union law for common-law couples (including gay and lesbian) revealed the depth of homophobic prejudice in its most vulgar form, including among eminent sociologists (such as Irène Théry). But they also permitted the emergence of positions on homosexuality from the heart of sociological study, that of family (notably the favorable and public positions taken by François de Singly), as well as the promotion of an entire series of studies on the sociological issues of the couple and parenthood.

In the end, ordinary heterosexism still pervades the field of sociology, especially in France. There is no laboratory or research network that has a program to study the issues directly linked to homosexuality and the social status of gays and lesbians. In this, the contrast with the US is staggering. However, even if dispersed or weak, the voices of sociologists is starting to be heard on the subject, and in an eminently positive sense, as demonstrated by the international meetings on gay and lesbian culture at the Centre Georges Pompidou in 1997, under the initiative of Eribon. There is the feeling that the years to come will strengthen this critical current, and that a new generation of sociologists will seize its discipline’s vast theoretical inheritance in order to enrich the international debate on homosexuality.

—Jean-Manuel de Queiroz

Becker, Howard S.

Outsiders: Studies on Sociology of Deviance

. New York: The Free Press, 1963.

Bersani, Leo.

Homos

. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1996.

Borrillo, Daniel, Eric Fassin, and Marcela Iacub, eds.

Au-delà du PaCS, l’expertise familiale à l’épreuve de l’homosexualité

. Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1999.

Butler, Judith.

Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity

. New York: Routledge, 1990.

Duyvendak, Jan Willem.

Le Poids du politique, nouveaux mouvements sociaux en France

. Paris: L’Harmattan, 1994.

Dynes, Wayne R., and Stephen Donaldson, eds.

Ethnographic Studies of Homosexuality

. New York: Garland, 1992.

Eribon, Didier, ed.

Les Etudes gays et lesbiennes

. Paris: Editions “Supplémentaires,” Centre Pompidou, 1998.

———.

Réflexions sur la question gay

. Paris: Fayard, “Histoire de la pensée”, 1999. [Published in the US as

Insult and the Making of the Gay Self

. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004.]

Goffman, Erving.

Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity

. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1963.

Herdt, Gilbert, and Andrew Boxer.

Children of Horizons: How Gays and Lesbians Teens are Leading a New Way out of the Closet

. New York: Beacon Press, 1993.

Kosofsky, Sedgwick Eve.

Epistemology of the Closet

. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1990.

Plummer, Kenneth.

Sexual Stigma: An Interactionnist Account

. London: Routledge, 1975.

Pollak, Michael.

Les Homosexuels et le Sida. Sociologie d’une épidémie

: Paris: Métailié, 1988.

———, and Marie-Ange Schiltz.

Les Homo- et bisexuels masculins face au Sida. Six années d’enquête

. Paris: GSPM, 1991.

Seidman, Steven, ed.

Queer Theory/Sociology

. Cambridge/ Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1996.

—Abnormal; AIDS; Anthropology; Biology; Class; Essentialism/Constructionism; Heterosexism; History; Medicine; Psychoanalysis; Psychology; Suicide; Symbolic Order.

SODOM AND GOMORRAH

The episode of Sodom and Gomorrah can be found in the book of Genesis (19:1–29). Visitors, who are either angels or men, appear at Lot’s house in Sodom. Lot entertains them well, but since the other inhabitants of the village want to “know” them (clearly, the verb has the sexual connotation), Lot must protect them; he even proposes his own daughters in exchange. The next day, God punishes the city as well as the city of Gomorrah by raining sulfur and fire upon them, a metaphor for Hell and divine punishment.

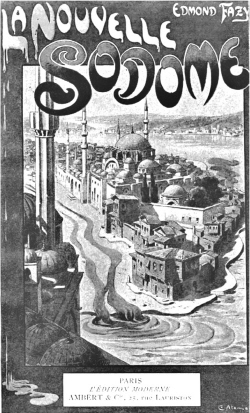

The biblical city, destroyed by divine wrath, inspired a literary and iconographical tradition, as indicated by French author Edmond Fazy’s novel, published in 1903 (cover illustrated by Jossot). Fazy was one of many writers who used allusions to Sodom to depict homosexuals as tainted.

Today, this very well-known passage represents the most evident biblical taboo against homosexuality, but in reality, it has not always been like that. The traditional exegesis has sometimes interpreted the passage as an offense against the rules of hospitality towards Lot’s visitors. Even better, the

Bible

itself (Epistle of Jude, verses 6-7) suggests a different form of transgression against God in this episode: the two visitors tried to establish undue relations between angelical and human orders; therefore, these angels disobeyed God by looking for an illicit business with men.

In other words, the privileged interpretation of Sodom and Gomorrah which condemns homosexual relations is not the only one in the Bible itself. Nevertheless, this condemnation appears as early as the second century BCE, when pious Jews violently criticized the influence of Greek morality and pederasty among their fellow citizens. Thereafter, this condemnation developed importantly among the first Christian thinkers (e.g., St Clement of Alexandria, John Chrysostom, and St Augustine), for whom homosexuality reflected a pagan way of life, before becoming a veritable common subject of religious rhetoric at the beginning of the thirteenth century.

—Thierry Revol

Ancien Testament [Old Testament]. Ecumenical translation of the Bible. Paris: Le Cerf/Les Bergers et les Mages, 1980.

Boswell, John.

Christianisme, tolérance sociale et homosexualité

. Paris: Gallimard, 1985. [Published in the US as

Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality

. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1980.]

Gilbert, Maurice. “La Bible et l’homosexualité,”

Nouvelle Revue de théologie

, no. 109 (1987).

Hallam, Paul.

The Book of Sodom

. New York: Verso, 1993.

Jordan, Mark.

The Invention of Sodomy in Christian Theology

. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1997.