The Dictionary of Homophobia (49 page)

As much from a scientific point of view as political, both the essentialist and constructivist approaches can be used in very different ways. It would be too simplistic to classify essentialists as conservative and all constructionists as progressive. It would be equally false to claim that both schools of thought are homogeneous and diametrically opposed. What is true is that certain approaches to sexuality, like those inspired by the sexological or biomedical disciplines, tend to be mostly essentialist—perhaps because the analysis is conducted in terms of normality and deviance. A discipline which favors research into the etiology of homosexuality (such as

endocrinology

,

genetics

,

psychiatry

,

psychology

, etc.) neglects the “causes” of heterosexuality, which is assumed to be “normal.” Other forms of essentialism can also be found in the humanities: some historians examine the existence of “gays” in the Middle Ages, for example, while anthropologists talk about “homosexuality” in Native Americans, and zoologists record species of animals in which “homosexual” behavior can be observed.

In political terms, the use of both approaches is not necessarily univocal. The goal behind the creation of the term “homosexual” in the mid-nineteenth century by militant Hungarian scholar Karl-Maria Kertbeny was to demonstrate the existence of a homosexual “true nature,” in order to keep gays and lesbians from being persecuted under Paragraph 175 of the German penal code. A large number of gay and lesbian militants during the latter half of the nineteeth century (including the famous sexologist Magnus

Hirschfeld

) adopted similar stances.

In the twentieth century, this kind of argument was also used, especially in research on the supposed biological origins of homosexuality—such as that conducted by neuroscientist Simon LeVay, who claimed there was a difference in the average size of the hypothalamus between heterosexual and homosexual men. According to the openly gay scientist, the size of the hypothalamus in a homosexual man is closer to that of a woman’s (though there is no mention of the woman’s sexual orientation). Note that this biological view has a difficult time accounting for additional variables, such as bisexuality (just how big would a bisexual hypothalamus be?), not to mention that it also poses certain ethical problems, as indicated by bioethicist Udo Schuklenk.

For some champions of contemporary gay and lesbian activism, establishing a scientific truth confirming the existence of a cause for homosexuality based in nature would be a way to “legitimize” their plight. The argument of a natural cause that would in effect “normalize” homosexuality would then serve to counteract all types of homophobic prejudices and social sanctions. This hearkens back to the same arguments used since the nineteenth century by other homosexual activists such as Germany’s Karl Heinrich Ulrichs. This reasoning, such as that behind the theory of the “third sex,” shows that the very concept of “nature” is adaptable to whatever use is required. Thus, the theories of a biological origin for homosexuality can also be applied to dangerous derivations that also claim scientific legitimacy, such as a supposed “cure” for homosexuality, or even medical intervention to “prevent” it from occurring.

The “scientific” quest for the origins of the social in the biological is an old demon that has, in the past, led to ideological manipulations that offer a pseudo-legitimacy to deterministic methods, of which eugenics, so dear to Nazi scientists and ideologists, is one of the darkest examples.

—

Rommel Mendès-Leite

Boswell, John. “Revolutions, Universals, and Sexual Categories.” In

Hidden from History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past

. Edited by George Chauncey, Martin Duberman, and Martha Vicinus. New York: Penguin Books, 1990.

De Cecco, John. “If You Seduce a Straight Person, Can You Make Them Gay? Biological Essentialism versus Social Constructionism.” In

Lesbian and Gay Identities

. Edited by John De Cecco and John Elia. New York: Harrington Press, 1993.

Foucault, Michel.

Histoire de la sexualité

. Vol. I : “La volonté de savoir.” Paris: Gallimard, 1976. [Published in the US as

The History of Sexuality

. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.]

LeVay, Simon. “A Difference in Hypothalamic Structure Between Heterosexual and Homosexual Men.”

Science

, no. 253 (1991).

MacIntosh, Mary. “The Homosexual Role.”

Social Problems

4 (1968).

Schuklenk, Udo. “Is Research Into The Cause(s) of Homosexuality Bad for Gay People?”

Christopher Street

, no. 208 (1993).

———. “Scientific Approaches to Homosexuality.” In

Gay Histories and Cultures: An Encyclopedia

. Vol. II. Edited by George E. Haggerty. New York/London: Garland, 2000.

Stein, Edward, ed.

Forms of Desire: Sexual Orientation and the Social Constructionist Controversy

. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Vance Carole. “Social Construction Theory: Problems in the History of Sexuality.” In

Homosexuality, Which Homosexuality?

Edited by Dennis Altman, Carole Vance, Martha Vicinus, and Jeffrey Weeks. Amsterdam/London: Uigeverij An Dekker-Schorer and GMP Publishers, 1989.

Weeks, Jeffrey.

Coming Out: Homosexual Politics in Britain from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

. London: Quartet Books, 1977.

—Anthropology; Biology; Gender Differences; History; Medicine; Philosophy; Psychology; Psychoanalysis; Sociology; Theology; Universalism/Differentialism.

EULENBURG AFFAIR, the

The scandal known as the Eulenburg affair (also referred to as the Harden-Eulenburg affair) was a series of court-martials and regular trials in Germany resulting from accusations of homosexual conduct among members of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s cabinet and entourage between 1907 and 1909. The episode upset German political life and sparked a wave of homophobia among the general public.

In 1886, Prince Philipp of Eulenburg-Hertefeld, a diplomat and aristocrat known for his artistic talents, struck up a close friendship with Kaiser Wilhelm II, to whom he became an advisor. Named ambassador to Austria-Hungary, his anti-imperialist stance and his readiness to reconnect politically with

France

earned him the resentment of the disciples of Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Despite the fact that he got married in 1875, it was a well-known secret that Eulenburg (as Prince Philipp was known) regularly engaged in homosexual acts. Beginning in 1893, he became the target of a press campaign initiated by journalist Maxmilian Harden, editor of the newspaper

Die Zukunft

, who threatened to reveal his personal life and forced him, in 1902, to resign.

In 1906, as Eulenburg began to renew his political career, the Algeciras Conference took place to resolve the crisis over the colonial status of Morrocco between France and Germany; the conference favored France, which had the support of Great Britain and the US, a serious setback for German foreign affairs. In the wake of this, Harden relaunched his accusations against Eulenburg, publishing various parodies which contained allusions to both him (referring to him as “the Harpist”) and to the Count Kuno von Moltke, military commander of Berlin (known as “Sweetie”) as homosexuals, perhaps under pressure from military circles which had been rocked by a series of homosexual

scandals

(between 1906 and 1907, six military officers committed suicide after being blackmailed for their homosexuality; previous to this, some twenty other officers were convicted by court-martials for being homosexual). Harden seemed to believe that his revelations would lead to a beneficial change in the

army

and the aristocracy, and would put an end to the spread of homosexuality, which was perceived as a sign of

decadence

. However, the campaign also had political motivations: both Eulenburg and Moltke were also suspected of having given privy information to the first secretary of the French embassy in Berlin, Raymond Lecomte (also gay), who was then purported to have revealed to the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs that Germany had been bluffing during the Algeciras Conference of January–April 1906.

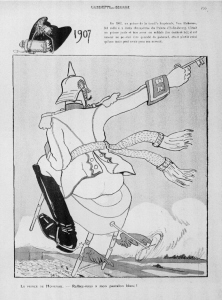

Image published in

L ’Assiette au beurre

, 1907. Its caption explains: “In 1907, a prince of the Imperial family, von Hohenau, was involved in the pastoral frolics of the Prince of Eulenburg. He was a good and just prince to soldiers (the

cuirassiers

); though this love could not quite be qualified as paternal, rather, more like that of an auntie for her nephews.” The artist also illustrated the prince speaking the famous words of Henri IV: “Rally round my white pants!”

The ultimate goal of Harden’s tactics was to weaken Wilhelm II by discrediting his entourage. Yet despite being in possession of compromising documents about the Kaiser’s sexuality, Harden refused to make use of them. On April 27, 1907, Harden officially outed both Eulenburg and Moltke, confirming their identities in his previously published parodies. In face of the scandal’s growing scope, Wilhelm II demanded Moltke’s resignation, and Eulenburg was obliged to quit the diplomatic service and give up his decorations. However, the affair was far from over; just as in Great Britain with regard to Oscar

Wilde

, the scandal led to the courtroom. Moltke began by launching a criminal libel suit against Harden. The trial opened on October 23, 1907, and quickly became sensational. The crowd pressed in to hear the revelations of Lili von Elbe, Moltke’s estranged wife, who testified that she had only had sexual relations with her husband on two occasions, and that he would place a pot full of water in the bed in order to discourage her advances. A soldier known as Bollhardt, who had participated in homosexual orgies organized by many renowned aristocrats, described to the court the attraction of the uniform worn by

cuirassiers

(mounted cavalry soldiers), and stated that homosexual relations were quite widespread within the army. Finally, Magnus

Hirschfeld

, the German sexologist and leader of the WHK (Wissenschaftlich-Humanitäres Komitee, or Scientific Humanitarian Committee, a gay movement fighting to abolish the homophobic Paragraph 175) testified as an “expert” and confirmed that Moltke’s “unconscious orientation” could be described as homosexual, after having witnessed his “feminine” sensibilities. The goal of Hirschfeld’s testimony was to denounce the hypocrisy of the German government, which ignored the homosexuality of those who were highly placed, while condemning anyone else. The tactic did not go as planned: on October 29, Harden was acquitted, although the trial was voided on the grounds of procedural defects. At the same time, another trial began: this one pitted Adolf Brand, publisher of the world’s first gay periodical

Der Eigene

(The special), against the chancellor of the German Empire from 1900 to 1909, Prince Bernhard von Bülow, who was suing him for libel. Brand, one of the originators of the “

outing

” phenomenon, had written a pamphlet describing how Bülow had been blackmailed for alleged homosexuality. Brand was sentenced to eighteen months in prison. In December, during the new trial of

Harden v. Moltke

, medical experts diagnosed Moltke’s wife as having hysteria, and Hirschfeld retracted his testimony. Harden was sentenced to four months in prison. The trial against Eulenburg was never completed, as the prince fell gravely ill; he died in 1921 without being acquitted, unlike Moltke.

The Eulenburg affair fomented a deep public prejudice toward the homosexual “cause.” Homophobic demonstrations abounded, often combined with anti-Semitic, anti-feminist, and anti-modernist movements, while arrests in the name of Paragraph 175 sharply increased. In the press,

caricatures

depicting homosexuals as effeminate or bestial (sometimes in the form of dogs or pigs) found a resurgence, just as the association of homosexuality with treason became more common: the testimony of Hirschfeld (who was Jewish and homosexual) during the trial led to whispers of a conspiracy between those two groups to bring about the downfall of the Empire. What is certain is that Hirschfeld had made a tactical error in testifying; as a result, financial support for his organization fell by two-thirds, a sign of the disaffection of the well-heeled homosexuals who had until then provided funding but who now feared being exposed. The ramifications of the affair were extreme and were felt beyond the borders of Germany, even if historians have long resisted recognizing this fact. In France, homosexuality began to be known as the “German

vice

,” Berlin was renamed “

Sodom-

sur-Sprée” (Sodom on the Spree, a reference to the river that runs through the city), and Germans themselves were referred to as “Eulenbougre” (

bougre

meaning a “bugger”). Even in French urinals, invitations to homosexual activity took on a new form: “Do you speak German?”

More generally, the Eulenberg affair marked a turning point in the representation of homosexuality: it saw the popularization of the term “homosexual,” which had previously been restricted to the medical domain but was now defined using psychological criteria such as effeminacy, passivity, or an artistic temperament. It would also open the door in Germany to the use of homosexuality for political ends, which would reach an apex during the 1930s.

—Florence Tamagne