The Dictionary of Homophobia (47 page)

Borell, Merriley. “Organotherapy and Reproductive Endocrinology,”

Journal of History of Biology

18, no. 1. Dordrecht: Reidel Publishing Company, 1985.

Oudshoorn, Nelly. “Endocrinologists and the Conceptualization of Sex, 1920–1940,”

Journal of History of Biology

23, no. 2 (1990).

———. “The Making of Sex Hormones,”

Social Studies of Science

20, no.1. London: Sage, 1990.

—Biology; Degeneracy; Fascism; Ex-Gay; Genetics; Himmler, Heinrich; Hirschfeld, Magnus; Inversion; Medicine; Medicine, Legal; Perversions; Psychiatry; Psychoanalysis; Treatment; Turing, Alan.

ENGLAND

Twelfth to Nineteenth Century

In England during the Middle Ages, the “crime of sodomy” fell under the jurisdiction of the clergy; ecclesiastical law provided for the imposition of the death penalty. The number of homosexuals condemned of this crime remains unclear, given that sodomy was also the name assigned to other crimes such as bestiality and heresy. Around 1090, under the reign of William II (Rufus), the chronicler Orderic Vital criticized the morals of Norman youth who grew their hair long, adopted effeminate characteristics, and practiced sodomy. Thus, when the ship carrying two such youths— the sons of Henry I, William and Richard—sunk in 1120, chroniclers such as Henry of Huntingdon and William of Nangis deemed the wreck a just punishment for their vice.

Around 1290, under the reign of Edward I, sodomy was punishable first by drowning, then by burning at the stake. One of the more famous victims of this law was Edward II, immortalized in a play by Christopher Marlowe which demonstrated how homosexuality is transgressive and can disrupt the strict hierarchical social order. According to his accusers, Edward II, under the influence of his constant companion Piers Gaveston, imperiled the kingdom by neglecting the legitimate nobility in favor of his favorite, thus placing personal matters ahead of the kingdom; and the criticism of his weakness (in which the reproach of his effeminacy is very present) laid the groundwork for a potential civil war. Political treachery combined with moral condemnation culminated in Edward II’s “exemplary” murder, by which a white-hot stake was driven up his anus. These dramatic machinations that were later depicted in Marlowe’s play proved eerily similar to the playwright’s own fate: Marlowe himself was accused of

treason

and

heresy

(he ascertained that Christ had a homosexual love for his disciple John) and was assassinated.

In 1533, a turning point in British homophobia occurred: in a conflict between Henry VIII and the papacy, Parliament decreed that sodomy (buggery) “with another human being or an animal” would fall under royal jurisdiction to be recognized as a felony. As a result, the “sodomite” was no longer only a sinner and debauched individual, but also a man without honor and an enemy of the state. This law, aimed at a precise sexual act and not a category of person, sought to protect the reproduction of the species by preventing the wrongful dispersion of the male seed; the law was again promulgated under Elizabeth I. Those accused of sodomy were judged by the tribunals and ran the risk of being hanged. However, by the time Elizabeth became queen in 1558, not only was the number of executions limited, so were the number of accused: in the counties of Essex, Hertfordshire, Kent, and Sussex, only four reported cases of sodomy were brought before the judges. By comparison, between 1558 and 1603, the county of Essex alone saw 15,000 people called before the court for sexual misconduct. Under the weight of biblical condemnation, the crime of sodomy was often considered unthinkable and thus not used to describe homosexual practices alone. Instead, the accusation of sodomy was more often used to discredit political or religious adversaries, such as during conflicts between Protestants and “papists.” Satire and ridicule seemed to be the preferred means by which to denounce the homosexual sympathies of the powerful: the posthumous printings of the 1684 play entitled

Sodom, or the Quintessence of Debauchery

by John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester (himself a bisexual), was a critique of the morals of the court of Charles II. The most famous sodomy

scandal

implicated Mervyn Touchet, Lord Audley, Earl of Castlehaven in 1631: in addition to multiple acts of sodomy with his servants, he was accused of abetting the rape of his wife and offering his twelve-year-old stepdaughter to his favorite servant in order to make him his heir; to the “

unnatural

” crime was added a crime against family honor. In 1640, the Bishop of Waterford was the last English man hanged for sodomy in the seventeenth century. During all this time, lesbianism remained outside of the law and seems to have attracted less interest than male homosexuality. It must be noted, however, the Sapphic friendships of Queen Anne were the object of caustic allusion on the part of satirists.

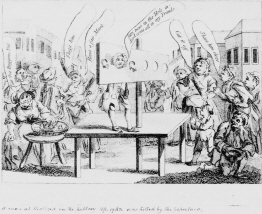

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, harsher repressive measures resulted in a change in representations of homosexuality. The figure of the libertine bisexual, which had dominated the preceding centuries, was progressively pushed aside by the moral bourgeoisie who advocated monogamy and the protection of the family, leading to homosexuality becoming an increasingly exclusive practice. As a result, a specific homosexual culture began to form around molly houses, places where gay men could rendezvous, which were centered in the Holborn quarter of London and around St James’s Park. In these clubs, shows were staged that parodied men getting married or even giving birth. Around 1690, Puritan associations, the Societies for the Reformation of Manners, had already begun to organize their surveillance of suspected homosexuals, and would soon orchestrate raids that would terrorize the homosexual population from 1710 to 1720, resulting in many homosexual men committing

suicide

. Hundreds were arrested and many of those convicted were hanged; still others were sent to the stocks, a humiliating and frightening experience that often ended in serious wounds or death. The general populace, including women, took advantage of such occasions to unleash its wrath, heaping garbage, rocks, and dead cats upon the unfortunate prisoner. In addition, abusive lampoons, often enhanced with woodcuts, were distributed to fuel the hatred, bearing titles such as

The Women’s Complaint to Venus

or

The Women Hater’s Lamentation

. The popular

literature

of the time, often expressing itself also through satire, was also susceptible to instances of homophobia: in Tobias Smollett’s

The Adventures of Roderick Random

, the eponymous hero must suffer the advances of Captain Whiffle and the Earl of Strutwell.

The eventual disappearance of the Puritan societies, discredited by their methods, did not signify the end of the persecution of homosexuals, however. Vengeful pamphlets such as

Satan Harvest Home

(1749) and

The Phoenix of Sodom

(1813) continued to be published in order to alert the public to the extent of homosexual networks. The 1810 scandal involving the Vere Street Coterie, a group of gay men arrested at a molly house called the White Swan, also contributed to the public’s homophobic prejudice. Meanwhile, the ongoing Napoleonic Wars reinforced a sense of insecurity among the English: the advance of homosexuality was attributed to the French, while the British Navy hardened its policy with regard to sodomy. For many homosexuals living in England, exile appeared to be the only solution, even more so as many European nations, following the French example, were

decriminalizing

sodomy. In order to escape rumors of their sexuality, both William Beckford, the richest man in England, and Lord Byron chose to live abroad, in Italy, Greece, and Portugal.

Stratford, 1763:

Man in the stocks put to death by the people:

“Take this Buggume pear! —Flog him! —Here’s a fair mark! —Cut it off! —Shave him close!” The sodomite appears to have learned his lesson: “Now I’m in the hole. Indeed, come all in my friends.”

Although lesbianism per se was not condemned, transvestism among women sometimes incurred the wrath of the law; while women who dressed as men in order to join their husbands on the field of battle were rarely pursued, those who used their disguise to affirm their autonomy or to engage in sexual relations with other women ran the risk of serious punishment. Mary Hamilton, whose case was invoked in Henry Fielding’s novel

The Female Husband

(1746), was publicly flogged for having illegally practiced medicine while disguised as a man. Generally speaking, lesbianism enjoyed a greater degree of

tolerance

because judges and public opinion were repelled at the very idea of the existence of female homosexuality. In 1811, Marianne Woods and Jane Pirie, teachers at the upper-class boarding school for girls in Drumsheugh, Scotland, were accused by Dame Helen Cumming Gordon of being lesbians; they sued for defamation and won because the presiding judge Lord Gillies refused to believe in the existence of the “presumed crime.”

Nineteenth Century to 1967

In the late nineteenth century, while certain English philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham were in favor of the decriminalization of homosexuality, the United Kingdom did not go in this direction. Certainly, in 1861, the penalty for a sodomy conviction was reduced from possible death to a prison sentence ranging from ten years to life. This punishment was again reduced in 1885 with the adoption of the Labouchere Amendment to the Criminal Law Amendment Act (which followed a number of scandals including the notorious 1871 trial of Boulton and Park, two transvestites), intended to change the laws concerning juvenile prostitution. Thereafter, “all acts of gross indecency” between two men were punishable by imprisonment for up to two years of hard labor. Although the amendment considerably reduced the potential duration the sentence, it broadened the scope of the law to specifically include all forms of sexual conduct between two men; as a consequence, it placed homosexuals at the mercy of blackmailers. Further, whereas the sodomy law of 1861 had been rarely enforced, the revised Criminal Law Amendment Act resulted in a considerable increase in the numbers of those accused and convicted. Homosexuals were again targeted in 1898, when the Vagrancy Act was extended to make homosexual solicitation illegal.

In the twentieth century, homosexuals were also the target of a smear campaign during World War I. Stigmatized as the “German vice” since the

Eulenburg affair

, homosexuality was seen as nothing else but the mark of traitors in power. While journalist Arnold White asserted that Germany intended to “abolish civilization as we know it, substitute

Sodom

and Gomorrah

for New Jerusalem, and infect the healthy nations with Hunnish erotomania,” Member of Parliament Noel Pemberton Billing took up an anti-homosexual crusade, contending that German Secret Services had in their possession a black book containing the names of 47,000 high-ranking homosexuals, whom the Germans were blackmailing. Also, in an article entitled “The Cult of the Clitoris,” he attacked actress Maud Allan, then appearing in a production of Oscar

Wilde

’s

Salomé,

accusing her of pro-lesbian propaganda.

During the period between the two world wars, there was an average of 702 arrests annually in the United Kingdom for homosexual crimes and misdemeanors, which were classified as “unnatural offences,” “acts of indecency,” or “attempt(s) to commit unnatural offences.” The number of arrests continuously increased during this period on a yearly basis. These figures reflected the concerns of the British judiciary, police, and military forces who gathered at a May 7, 1931 conference on homosexual crimes, which sought to put an end to the sexual activities of soldiers of the Guard in the parks of the capital, among other matters.

Police harassment sometimes resulted in raids on London’s gay bars, but it most often consisted of surveillance of urinals by plainclothes policemen, in keeping with the ongoing fear of “

contagion

.” Generally speaking, the homosexual criminal was viewed with contempt by those in law enforcement who made every effort to publicize the outward “signs” of his “perversion”: powder compact, makeup, and petroleum jelly. However, these police actions themselves did not increase the number of arrests or convictions due to the difficulty in catching the guilty in the act as well as the reluctance of witnesses to testify. But the objective was less a desire to make arrests than it was to maintain pressure on regulars who frequented the bars and urinals. In this sense, homosexuals who cruised public areas, be it by preference or by need for lack of companionship, were the most at risk. The working classes were thus overrepresented in the statistics of those arrested. In addition, in an effort to shield the privileged, the British government attempted to silence any case implicating known figures, a tradition going back decades to the Cleveland Street scandal (1889–90), in which a number of aristocrats, such as Prince Albert Victor, son of the Prince of Wales, had been involved. However, while the trials of Oscar Wilde, which saw the writer cast out from British society, contributed to bringing homosexuality into the British public eye, they also reinforced the prejudices of public opinion that associated homosexuality with high society, debauchery, and effeminacy. At this point, homophobia attained its apex in the United Kingdom, resulting in many homosexuals choosing to immigrate to France rather than run the risk of dishonor. The very name of Oscar Wilde became synonymous with vice and corruption for years to come.