The Domesticated Brain (18 page)

Read The Domesticated Brain Online

Authors: Bruce Hood

Tags: #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience

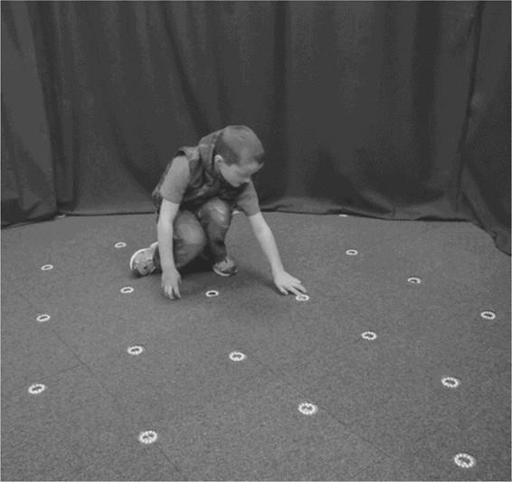

Figure 8: Searching for targets in our ‘foraging’ room

Again this is a pattern that you see in normal development. Young children often get stuck in routines and indeed often seem to like repetition. It may be the familiarity they enjoy or it may be that they lack the flexibility to process changing information. This lack of flexibility is again related to the immaturity of the PFC, which no only keeps thoughts in mind, but also prevents us doing things that are not longer appropriate. This is why babies will continue to reach directly for a desirable toy in a clear plastic box only to discover that they cannot grasp it when their tiny hands bash up against the edge of the box.

20

Even though the side of the clear box is open and they can reach around to retrieve the toy, the sight of the goal is so compelling that they keep reaching directly for it. If you cover the object so that it is out of sight, they then learn to stop reaching directly for it. Something about the sight of the toy compels them to act. It’s like showing an addict the fix they so desperately seek; they cannot avoid the temptation.

Even well-adjusted adults are not immune from doing the first thing that pops into their heads. One simple way to demonstrate this problem of inhibitory control is the

Stroop test

– a very simple task where you have to give an answer as quickly as possible in a situation where there is competition or interference from another response.

21

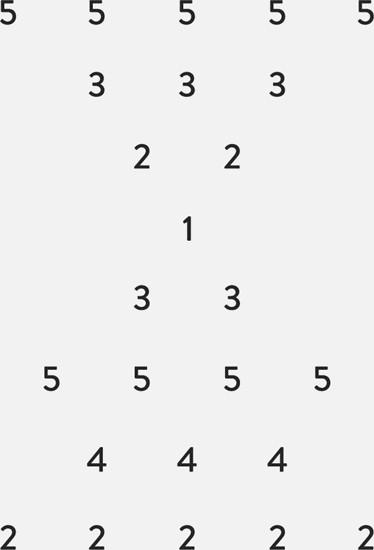

The most familiar version of the task can be found in a number of ‘brain-training’ games where you have to name the colour of ink that a word is written in. The task is easy if the word is ‘red’ and it is written in red ink. More difficult is when the word is ‘green’ but is written in red ink, because there is a conflict between naming the ink and the tendency to automatically read the word. Here is another Stroop task that you may not have encountered. Try counting the number of digits in each line as fast as you possibly can.

How many numbers are there in each row?

If you were answering as fast as you can, then you will have found the first four rows very easy but the next four much harder. You probably made mistakes, and if not, then you were probably much slower. Like the sight of a desirable toy for a baby, digits trigger the impulse to read them. As the digit conflicted with the number of items in some of the lines, the word had to be inhibited in order to give the correct answer.

If you break down a complex task into a list of things to do, then you can readily see why inhibition is so critical to performance. Some tasks need to be carried out in sequence, which is why I was hopeless at building model airplanes. I

am too impulsive for the task – something that was evident as a child when I always wanted to start painting my models before they were fully assembled. I lacked the patience that such hobbies require. This is why inhibition is necessary for planning and controlling behaviour by avoiding thoughts and actions that get in the way of achieving your goals. We can all experience this to some extent and it changes as we age. As we grow elderly, we become stuck in our ways. We lose flexibility of thought and can become more impulsive. Both the stubbornness and impulsivity are linked to the diminishing activity of our frontal lobes, which is just part of the normal ageing process. As we age, the PFC and its connections that regulate behaviours deteriorate faster than other brain areas.

22

At the beginning and the end of life, we lack the flexibility provided by our frontal lobes.

Disinhibited party animals

The EFs are not only important for reasoning, but play a vital role in our domestication that enables us to coordinate personal thoughts and behaviour with the wishes of others. They become facets of our personality that reflect the way we behave. Given their central role in shaping how we behave, you might imagine that the slightest damage to the PFC would immediately alter our personalities, but impairments in adult patients with frontal lobe damage are not always that easy to spot. Their language is usually intact and they also score within the normal range on IQ measures. However, frontal-lobe damage does change people in profound ways. Patients can be left unmotivated, with a dull, flat

affect. Others can become very antisocial, doing things that the rest of us find unacceptable because they no longer care about the consequences of their behaviour.

23

Frontal-lobe damage may mean living for the moment, but this state is not as appealing as it might seem. Imagine if you suddenly no longer thought about getting on in life or how other people viewed your behaviour. Forget planning for the future and avoiding things that might get you into trouble. You would become reckless with money and people. You would do whatever took your fancy, no matter what the consequences. It would be hard to trust such a person. Frontal-lobe-damaged patients may seem normal, but they are often irresponsible, lack appropriate emotional displays and have little regard for the future. They find it difficult to tolerate frustration and react impulsively to minor irritations that the rest of us would let pass.

The most famous case of a change in personality following frontal-lobe damage is Phineas Gage, a twenty-five-year-old foreman who worked for the Rutland & Burlington Railway Company. On 13 September 1848, he was blasting away rocks to clear the way for the rails. To do this, a hole was drilled into the rock, packed with gunpowder, covered with sand and then tamped down with an iron rod to seal the charge. On that fateful day, apparently Phineas was distracted momentarily. He dropped the rod directly on to the gunpowder, igniting it to create an explosion that shot the 6ft metal rod through his left cheekbone under the eye and out the top of his skull to land 60ft away, taking a large part of his frontal lobes with it.

Remarkably, Phineas survived but he was noticeably changed in personality. According to the physician that looked after him, before the accident Phineas was ‘strong and active, possessed of considerable energy of character, a great favorite with his men’ and ‘the most efficient and capable foreman’. After the accident, the doctor produced a report to summarize why the railway company would not re-employ him. Phineas was described as ‘fitful, irreverent, grossly profane and showed but little deference for his fellows’. He was ‘impatient of restraint or advice that conflicted with his desires’. In short, he had become a grumpier, ruder, more argumentative person, such that his former friends and acquaintances said he was ‘no longer Gage’.

Due to the power of brain plasticity, Gage did eventually recover well enough to hold down another job as a stagecoach driver, but it is not clear whether his personality ever returned to that of the likeable fellow he had been before the accident. There has been considerable debate about Phineas Gage and whether his personality was permanently changed because the records at the time were poorly kept.

24

The story has been retold many times and something of a myth has been built up around this famous case. We have a much clearer picture with Alexander Laing, a former trooper in the British Army Air Corp, who is a modern-day Phineas Gage.

25

Following a skiing accident in 2000, Alexander suffered frontal-lobe brain damage that left him paralysed and unable to speak. He recovered quickly but on returning home became very antisocial, aggressive and unable to suppress his sexual urges. He is reported to have walked around his parents’ house naked and acted inappropriately to women

in public. At the time, his stepmother said, ‘The damage to Alexander’s frontal lobes seems to have exaggerated his character, although experts aren’t sure if this is the case. I think the impulses were always there, but the lack of inhibition means he cannot control himself.’ Of the time around his injury Alexander recalled ten years later, ‘The frontal lobe damage was the worst. It meant I lost my inhibitions and did stupid things. It was like being permanently drunk. Afterwards I got into trouble of all sorts, I was even arrested twice. It was not a good time.’

Today, Alexander runs marathons for charity and seems to have got the better of his impulses, though his personality will probably never be the same as before the injury. During the 2011 London Marathon, he stopped after running 23 miles and began an impromptu dance in response to a Gospel choir performing at the side of the road to encourage runners, much to the delight of the gathered crowds. Only after the intervention of a medic assisting at the marathon was Alexander persuaded to stop dancing and return to the race. He believes that religion has kept him on the straight and narrow, showing that with the right social support, patients with frontal-lobe damage can experience considerable recovery. It also helps that we now have a better medical understanding of the importance of the frontal lobes in controlling our impulses. These cases reveal what happens to adults’ social behaviours following damage to the frontal lobes. Understanding the relationship between EF and the frontal lobes helps explain why young children often behave in a way in which they seem oblivious to others around them and the embarrassment they create for their parents. Their

immature frontal lobes have not yet been tuned up by the processes of domestication in the ways of how to conduct oneself in public.

Temper tantrums

‘Daddy, I want it and I want it now!’

Who can forget Veruca Salt, the spoiled brat in Roald Dahl’s

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

who got everything she wanted? She may have been obnoxious but she really was no different from many young children when they cannot get their way. Around the end of infancy, children enter a phase that parents refer to as the ‘terrible twos’. At this age, children have sufficient communication skills to let others know what they want but they are unwilling to accept no for an answer. It is a very frustrating time for parents because unless they give in to their child’s demands the child can throw a temper tantrum – often for the benefit of a full public audience in a shopping mall or theatre. There is no point trying to reason with most two-year-olds because they do not understand why it is in their interests not to have what they want immediately. That requires the silent manager of the PFC to speak up.

One way to think about the PFC is that rather than supporting just one type of skill, it is engaged in all aspects of human behaviours and thoughts. As we grow older, our behaviours, our thoughts and our interests change. Situations that require some level of coordination and integration will require the activity of the frontal lobe EFs which do not reach mature levels of functioning until late adolescence.

26

When adults have to learn a new set of information that conflicts with what they already believe to be true, there is heightened PFC activation during the transition phase, as revealed by functional brain imaging. One interpretation is that they are simply concentrating more, enlisting greater EF activity, but that activation depends on whether they have to contradict their initial beliefs. In this situation, the PFC activity is interpreted as reconciling incompatible ideas by inhibiting and suppressing knowledge that they previously held.

27

So rather than regarding any limited ability as being due to immaturity of the PFC, it is probably more accurate to say that changing behaviours and thoughts have not yet been fully integrated into the individual’s repertoire – they are still learning to become like others.

In many social situations, young children think mostly about themselves, which explains why their interactions can be very one-sided. Some of us never grow out of this type of behaviour. These are the selfish individuals we all have encountered who only think about themselves. They do not care about what others think and behave as if their needs and opinions are the only important things in the world. They lack the patience and understanding that is required to have a balanced social relationship.