The Eyes of the Dragon (41 page)

Read The Eyes of the Dragon Online

Authors: Stephen King

If he's going to kill you, make HIM do it! Don't do it

for him!

for him!

The thought came from inside his own head . . . but it sounded like his mother's voice. Peter's hands steadied a bit, and he began to knot the end of his rope to his anchor again.

118

I

'

ll carry

your head on my saddle horn

for a thousand years!”

Flagg screamed. Up and up, around and around.

“Oh, what a pretty trophy you'll make!”

'

ll carry

your head on my saddle horn

for a thousand years!”

Flagg screamed. Up and up, around and around.

“Oh, what a pretty trophy you'll make!”

Twenty. Thirty. Forty.

His bootheels struck green fire from the stones. His eyes glared. His grin was poison.

“HERE I COME, PETER!”

Seventyâtwo hundred and thirty steps to go.

119

I

f you have ever awakened in a strange place in the middle of the night, you'll know that just to be alone in the dark can be frightening enough; now try to imagine waking in a secret passage, looking through concealed eyeholes into the room where you saw your own father murdered!

f you have ever awakened in a strange place in the middle of the night, you'll know that just to be alone in the dark can be frightening enough; now try to imagine waking in a secret passage, looking through concealed eyeholes into the room where you saw your own father murdered!

Thomas shrieked. No one heard him (unless the dogs below did, and I doubt thatâthey were old, deaf, and making too much noise themselves).

Now, there was an idea about sleepwalking in Delainâone that has also been commonly held as the truth in our world. This idea is that if a sleep . walker wakes up before returning to his or her bed, he or she will go mad.

Thomas might have heard this tale. If so, he could attest that it wasn't true at all. He'd had a bad scare, and he had screamed, but he did not come even close to going mad.

In fact, his initial fright passed rather quicklyâmore quickly than some of you might thinkâand he looked back into the peepholes again. This may strike some of you as strange, but you have to remember that, before the terrible night when Flagg had come with his own glass of wine after Peter left, Thomas had spent some pleasant times in this dark passageway. The pleasantness had a sour undertone of guilt, but he had also felt close to his father. Now, being back here, he felt a queer sense of nostalgia.

He saw that the room had hardly changed at all. The stuffed heads were still thereâBonsey the elk, Craker the lynx, Snapper the great white bear from the north. And, of course, Niner the dragon, which he now looked through, with Roland's bow and the arrow Foe-Hammer mounted above it.

Bonsey . . . Craker . . . Snapper . . . Niner.

I remember all their names,

Thomas thought with some wonder.

And I remember you, Dad. I wish you were alive now and that Peter was free, even if it meant no one even knew I was alive. At least I could sleep at night.

Thomas thought with some wonder.

And I remember you, Dad. I wish you were alive now and that Peter was free, even if it meant no one even knew I was alive. At least I could sleep at night.

Some of the furniture had been covered with white dust-sheets, but most had not. The fireplace was cold and dark, but a fire had been laid. Thomas saw with mounting wonder that even his father's old robe was still there, hung in its accustomed place on the hook by the bathroom door. The fireplace was cold, but it wanted only a match struck and held to the kindling to bring it alive, roaring and warm; the room wanted only his father to do the same for it.

Suddenly Thomas became aware of a strange, almost eerie desire in himself; he wanted to go into that room. He wanted to light the fire. He wanted to put on his father's robe. He wanted to drink a glass of his father's mead. He would drink it even if it had gone bad and bitter. He thought . . . he thought he might be able to sleep in there.

A wan, tired smile dawned on the boy's face, and he decided to do it. He wasn't even afraid of his father's ghost. He almost hoped it would come. If it did, he could tell his father something.

He could tell his father he was sorry.

120

G

OMING, PETER!” Flagg shrieked, grinning. He smelled like blood and doom; his eyes were deadly fire. The headsman's axe swished and whickered, and a last few drops of blood flew from the blade and splashed on the walls.

“COMING NOW! COMING FOR YOUR HEAD

!”

OMING, PETER!” Flagg shrieked, grinning. He smelled like blood and doom; his eyes were deadly fire. The headsman's axe swished and whickered, and a last few drops of blood flew from the blade and splashed on the walls.

“COMING NOW! COMING FOR YOUR HEAD

!”

Up and around, up and around, higher and higher. He was a devil with murder on his mind.

A hundred. A hundred and twenty-five.

121

E

aster,” Ben Staad panted to Dennis and Naomi. The temperature had begun to fall again, but all three of them were sweating. Some of the sweat came from exertionâthey were working very hard. But much of their sweat had been caused by fear. They could hear Flagg shrieking. Even Frisky, with her brave heart, felt afraid. She had withdrawn a little and huddled on her haunches, whimpering.

aster,” Ben Staad panted to Dennis and Naomi. The temperature had begun to fall again, but all three of them were sweating. Some of the sweat came from exertionâthey were working very hard. But much of their sweat had been caused by fear. They could hear Flagg shrieking. Even Frisky, with her brave heart, felt afraid. She had withdrawn a little and huddled on her haunches, whimpering.

122

C

OMING, YOU LITTLE WHELP!” Closer nowâhis voice was flatter, with less echo.

OMING, YOU LITTLE WHELP!” Closer nowâhis voice was flatter, with less echo.

“COMING TO DO WHAT I SHOULD HAVE DONE A LONG TIME AGO!

”

”

The twin blades swished and whickered.

123

T

his time the knot held.

his time the knot held.

Gods help me

, Peter thought, and looked back once more toward the sound of Flagg's rising, shrieking voice.

Gods help me now.

, Peter thought, and looked back once more toward the sound of Flagg's rising, shrieking voice.

Gods help me now.

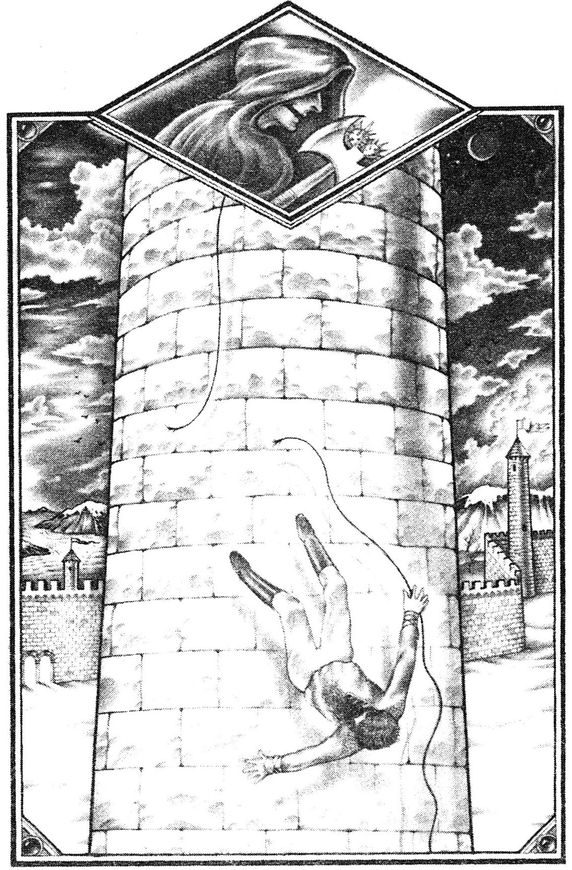

Peter threw one leg out the window. Now he sat astride the sill as if it were Peony's saddle, one leg on the stone floor of his sitting room, the other dangling over the drop. He held the heap of his rope and the iron bar from his bed in his lap. He tossed the rope out the window, watching as it fell. It tangled and bound up halfway down, and he had to spend more time shaking the rope like a fishline before it would drop free again.

Then, uttering one final prayer, he grasped the iron bar and pulled it against the window. His rope hung down from the middle. Peter slipped the leg that was inside over the sill, twisted around at the waist, holding on to the bar for dear life. Now only his bottom was on the sill. He made a half-turn so that the cold outer edge of the sill was pressed against his belly instead of his butt. His legs hung down. The iron bar was seated firmly across the window.

Peter let go of it with his left hand and caught hold of his narrow napkin rope. For a moment he paused, battling his fear.

Then he closed his eyes and let go of the bar with his right hand. His whole weight was on the rope now. He was committed. For better or worse his life now depended on the napkins. Peter began to lower himself.

124

C

OMINGâ”

OMINGâ”

Two hundred.

“FOR YOUR HEADâ”

Two hundred and fifty.

“MY DEAR PRINCE!”

Two hundred and seventy-five.

“FOR YOUR HEADâ”

Two hundred and fifty.

“MY DEAR PRINCE!”

Two hundred and seventy-five.

125

B

en, Dennis, and Naomi could see Peter, a dark man-shape against the curved wall of the Needle, high above their headsâhigher than even the bravest acrobat would dare to go.

en, Dennis, and Naomi could see Peter, a dark man-shape against the curved wall of the Needle, high above their headsâhigher than even the bravest acrobat would dare to go.

“Faster,” Ben pantedâalmost moaned. “For your lives . . . for his life!”

They went about emptying the cart even faster . . . but in truth, all they could do was almost done.

126

F

lagg raced up the stairs, his hood falling back, his lank dark hair flying off his waxy brow.

lagg raced up the stairs, his hood falling back, his lank dark hair flying off his waxy brow.

Almost there nowâalmost there.

127

T

he wind was light now, but very cold. It blew against Peter's bare cheeks and bare hands, numbing them. Slowly, slowly, he descended, moving with careful deliberation. He knew that if he let his descent get out of hand, he would fall. In front of him, the great mortared stone blocks rolled steadily upwardâvery soon he came to feel that he was remaining still and it was the Needle itself which was moving. His breath came in tight gasps. Cold dry snow rattled on his face. The rope was thinâif his hands grew much number, he wouldn't be able to feel it at all.

he wind was light now, but very cold. It blew against Peter's bare cheeks and bare hands, numbing them. Slowly, slowly, he descended, moving with careful deliberation. He knew that if he let his descent get out of hand, he would fall. In front of him, the great mortared stone blocks rolled steadily upwardâvery soon he came to feel that he was remaining still and it was the Needle itself which was moving. His breath came in tight gasps. Cold dry snow rattled on his face. The rope was thinâif his hands grew much number, he wouldn't be able to feel it at all.

How far had he come?

He didn't dare look down and see.

Above him, individual strands of thread, cunningly woven together as a woman might braid a rug, had begun to pop threads. Peter did not know this, which was probably just as well. The breaking strain had nearly been reached.

128

E

aster, King Peter!” Dennis whispered. The three of them had finished emptying the cart; now they could only watch. Peter had descended perhaps half of the distance.

aster, King Peter!” Dennis whispered. The three of them had finished emptying the cart; now they could only watch. Peter had descended perhaps half of the distance.

“He's so high,” Naomi moaned. “If he fallsâ”

“If he falls, he'll be killed,” Ben said with a flat and toneless finality that silenced them all.

129

F

lagg reached the top of the stairs and ran down the corridor, his chest heaving as he gasped for breath. Sweat stood out all over his face. His grin was huge, horrible.

lagg reached the top of the stairs and ran down the corridor, his chest heaving as he gasped for breath. Sweat stood out all over his face. His grin was huge, horrible.

He put his great axe down and pulled the first of the three bolts on the door to Peter's quarters. He pulled the second . . . and paused. It would not be smart to simply go rushing in, oh no, not smart at all. The caged bird might be trying to fly the coop right this moment, but he might also be standing to one side of the door, ready to brain Flagg with something the moment he rushed in.

When he opened the spyhole in the middle of the door and saw the bar from Peter's bed placed across the window, he understood everything and roared with rage.

“Not so easy as that, my young bird!”

howled Flagg.

“Let's see how you fly with your rope cut,

shall we?”

howled Flagg.

“Let's see how you fly with your rope cut,

shall we?”

Flagg yanked the third bolt and charged into Peter's room with his axe held high over his head. After one quick look out the window, his grin resurfaced. He decided not to cut the rope, after all.

130

D

own and down Peter went. His arm muscles trembled with exhaustion. His mouth was dry; he couldn't remember ever wanting a drink as badly as he did right now. It seemed that he had been on this rope for a very, very long time, and a queer certainty had stolen into his heartâhe would never get the drink of water he wanted. He was meant to die after all, and that wasn't even the worst of it. He was going to die thirsty. Right now that seemed the worst of it.

own and down Peter went. His arm muscles trembled with exhaustion. His mouth was dry; he couldn't remember ever wanting a drink as badly as he did right now. It seemed that he had been on this rope for a very, very long time, and a queer certainty had stolen into his heartâhe would never get the drink of water he wanted. He was meant to die after all, and that wasn't even the worst of it. He was going to die thirsty. Right now that seemed the worst of it.

He still did not dare look down, but he felt a queer compulsionâevery bit as strong as his brother's compulsion to go into their father's sitting roomâto look up. He obeyed itâand some two hundred feet above, he saw Flagg's white, murderous face grinning down at him.

“Hello, my little bird,” Flagg called down cheerfully. “I've an axe, but I really don't think I'll need to use it after all. I've put it aside, see?” And the magician held out his bare hands.

All the strength was trying to run out of Peter's arms and handsâjust the sight of Flagg's hateful face had done that. He concentrated on holding on. He couldn't feel the thin rope at all anymoreâhe knew he still had it because he could see it coming out of his fists, but that was all. His breath rasped in and out of his throat in hot gasps.

Now he looked down . . . and saw the white, upturned circles of three faces. Those circles were very, very smallâhe was not twenty feet above the frozen cobbles, or even forty feet; he was still a hundred feet up, as high as the fourth floor of one of our buildings.

He tried to move and found he could notâif he moved, he would fall. So he hung there against the side of the building. Cold, gritty snow blew in his face, and from the prison above, Flagg began to laugh.

131

W

hy doesn't he

move

?” Naomi cried, digging one mittened hand into Ben's shoulder. Her eyes were fixed on Peter's twisting form. The way it hung there, slowly turning, made it look dreadfully like the body of a man who had been hanged. “What's

wrong

with him?”

hy doesn't he

move

?” Naomi cried, digging one mittened hand into Ben's shoulder. Her eyes were fixed on Peter's twisting form. The way it hung there, slowly turning, made it look dreadfully like the body of a man who had been hanged. “What's

wrong

with him?”

“I don'tâ”

Above them, Flagg's chilly laughter abruptly stopped.

“Who goes there?” he called. His voice was like thunder, like doom. “Answer me, if you want to keep your heads!

Who goes there?

”

Who goes there?

”

Frisky whined and shrank against Naomi's side.

“Oh gods, now you've done it,” Dennis said. “What do we do, Ben?”

“Wait,” Ben said grimly. “And if the magician comes down, fight. We wait for what happens next. Weâ”

But that was all the waiting any of them had to do, for in the next few seconds, muchânot all, but a great deatâwas resolved.

132

F

lagg had seen the thinness of Peter's rope, its whitenessâand in a trice he understood everything, from beginning to endâthe napkins and the dollhouse as well. Peter's means of escape had been under his nose the whole time, and he had very nearly missed it. But . . . he saw something else as well. Little pops of fiber where the strands were giving way, some fifteen feet down the taut length of rope.

lagg had seen the thinness of Peter's rope, its whitenessâand in a trice he understood everything, from beginning to endâthe napkins and the dollhouse as well. Peter's means of escape had been under his nose the whole time, and he had very nearly missed it. But . . . he saw something else as well. Little pops of fiber where the strands were giving way, some fifteen feet down the taut length of rope.

Flagg could have turned the iron bar he was resting his hand on and sent Peter plummeting that way, with the anchor trailing after to perhaps bash his head in when he struck bottom. He could have swung the battle-axe and parted the fragile rope.

Other books

Man Who Wanted Tomorrow by Brian Freemantle

A Wizard of the White Council by Jonathan Moeller

Natalya by Wright, Cynthia

Las cruzadas vistas por los árabes by Amin Maalouf

Broken Mage by D.W. Jackson

ROMAN: Fury of Her King (Kings of the Blood Book 2) by Julia Mills

Treespeaker by Stewart, Katie W.

Return to Me by Morgan O'Neill

A Darkness at Sethanon by Raymond Feist

Joyce's War by Joyce Ffoulkes Parry